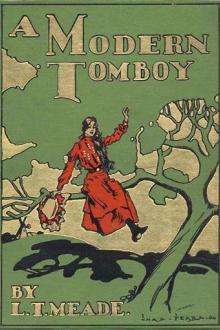

A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls by L. T. Meade (mini ebook reader TXT) 📗

- Author: L. T. Meade

Book online «A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls by L. T. Meade (mini ebook reader TXT) 📗». Author L. T. Meade

"There are two years between us; but then, Agnes is so very small, so petite in every way, and so—so sweet and so defenseless."

"I always thought you did not care for defenseless people, nor for weak people, nor timid people."

"Oh, I like her sort. You see, she believed in me from the first."

"I hope she always will," said Rosamund.

"Well, where is she now?"

"She has gone to talk to her sister. You cannot expect her to give up all her time to you."

"But indeed that is just what I do. What can she have in common with that tiresome, frowzy old Frosty?"

"Only she happens to be her sister, and that tiresome, frowzy old Frosty, as you call her, has looked after her since she was a little child, when her mother died."

"Oh, yes, I've heard all that story. I suppose it's very noble; but, all the same, little Agnes is fonder of me."

"You have no right to steal her heart from Miss Frost."

"Rosamund, I don't know what to make of you. You always have a great influence over me; but what is the matter now? Do you want to take Agnes away from me? If you wish to, you may; but I shall follow, for I don't intend to give her up, and nobody living will make me. I am sure you can do what you like with that detestable Hugh, and Frosty can go for her holidays. It would be a very good idea. Agnes and I would be quite happy at The Follies, with dear mother, of course, to take care of us."

Just at that moment there came a whoop and a spring, and Hughie, his red face redder than ever, his freckles more marked, his carroty hair sticking up all over his head, and his light-blue eyes wearing a most mischievous expression, entered the little arbor and sat down at one side of Irene.

"I say," he remarked, "I want to ask you a direct question."

"What is that?" she said, moving slightly away from him.

He edged a little nearer.

"Is it true that you gave sister Emily horrid live things that curled themselves up into so-called pills, and she swallowed them and nearly died afterward? Is it true—tell me?"

"It's quite true," said Irene, all the dancing wickedness coming to the front at once, and her eyes blazing with anger.

"Then you are a really wicked girl. You might have been had up by the police and put into prison."

"And what if I had, you wicked boy—for you are about the wickedest and rudest boy I have ever come across? Much do I care! I wanted her to go, and I thought that would be a good way to get rid of her."

"Oh, that's all right!" said Hugh. "I'll just go and tell Agnes. I'll tell her that you'll do things of that sort to her, that you are a sort of witch, and will show your true colors before long. Now, what is the matter?"

"You sha'n't tell her. You daren't!" said Irene.

She caught both his hands as though in a vise. He was amazed at their strength, also at the beautiful, extraordinary passion of her face. Rosamund started up to interfere.

"Come, children," she said, "don't quarrel. Hughie, you do extremely wrong to speak in that tone to Irene. Come and have a walk with me. You know I am going away to-morrow, and I wouldn't have asked Irene to invite you both to this beautiful house, and to give you such a splendid holiday, if I hadn't thought you were going to be quite good. Ah! here comes Agnes."

Agnes was seen flying across the lawn. She was wearing a pretty white dress, and her whole dainty little figure, with her light hair flying wildly behind her, made her a most charming little picture. She dashed up to Irene, flung her arms round her neck, and kissed her passionately.

"Oh," she said, "it seemed hours while I was away from you! I was with Emily, and Emily says that perhaps I had better not eat plums—at least not more than one or two."

"Then I'll pick out the ripest in the basket for you," said Irene, her voice trembling.

"You take care there are no—no live things"——

"Hush, Hughie! Come with me," said Rosamund; and she pulled the reluctant boy out of the summer-house.

"Now, Hughie," she said when she had got him quite by herself, "I want to know, in the first instance, exactly how old you are."

"I was fourteen my last birthday," he said, drawing himself up to his full height.

"You suppose yourself to be a good bit of a man, don't you?"

"Well, I'm not far from being a man, am I, Rosamund? You don't mind my calling you Rosamund, do you?"

"You may call me anything in the world you please."

"Well, I'll call you Rosamund, because all the rest of the people here do; but by-and-by perhaps I shall be behind a counter, and you will come in and ask for stationery—I want particularly to go into a stationer's shop—or any other article you fancy, and I'll have to say, 'Yes, miss.' That is, unless you're married. You'll be much too grand to notice me in those days, won't you, Rosamund?"

Rosamund turned and looked calmly at him.

"Hugh," she said, "I'll never be too grand to take notice of you if you turn out the sort of boy I expect you to be."

"And what is that?" he asked, touched and astonished at her words.

"Well, now, I want you to undertake a rather difficult office."

"Oh, I say, and these are holidays!" grumbled the boy.

"Nevertheless, even in holidays a true boy, who means to be a true man, will act according to the best of his abilities; and what I want you to do now is to help and not hinder me with regard to Irene."

"That horrid, spiteful, handsome little witch?" said the boy.

"You admit that she is handsome?"

"I should rather think so. I never saw such eyes or such a face. But she's a horrid little thing for all that. Last night I was in the pantry, and James told me a lot of things about her; how she used to get wasps to sting him, and how she frightened away such a lot of servants from the place with leeches and toads, and all sorts of horrors. He said he didn't believe she was a girl at all, but that she was a sort of half-witch; and she is having that effect now upon our dear little Agnes, for Agnes doesn't care a bit for any one but her. She likes to spend all her time with her. She even insists on sleeping in her bed at night, and poor old Emily never gets a sight of Agnes, nor do I; and if it weren't for you I don't know where we'd be."

"Well, I'm leaving to-morrow," said Rosamund; "and it is just because I am leaving—and I am forced to go—that I intend to put a trust in you. I intend to tell you all about Irene—there is no other way to manage a boy like you; but I intend to tell you in such a way that you must give me your word of honor you will never repeat what I say."

"You have a queer way of talking," replied the lad, "and you do look wonderfully handsome, and unlike any other girl I ever saw. Little Aggie is a poor sort, you know. She is very sweet and pretty, and gentle and easily influenced."

"She is a dear little soul," said Rosamund, "and I don't wonder that you and your sister love her so much."

"Of course we love her; that is just what I say to Em. Of course we love her, and I don't think it is right of Emily to spend all her time crying. Her eyes are as red as anything. I never saw anything like it; and whenever she talks to me it is to say something of the way Agnes has forsaken her; and Agnes is quite unsuspicious."

"That is just it, and I want her to be unsuspicious. You must be kind to poor Frosty—forgive me, we always call her Frosty; but at the same time she must exercise the wonderful and healing influence she possesses over Irene."

"What do you mean by that?"

"You see, Irene is a very fine character"——

Hugh whistled.

"A fine character!" he said. "What about the toad in the bread-pan? What about the horrid live things she made poor dear Emily swallow? If Em had died, she'd have been had up for murder."

"It was a cruel and wicked thing to do; but I am sure she would never do it now—that is, unless you goaded her to it. You are in the mood to torment her to do wrong things. It is exceedingly wicked of you, and I tell you plainly I don't know what I shall do if all my hard work of the whole summer will be overthrown, unless you make me a solemn promise before I leave."

"Well, it is good of you to trust me," said Hughie, softening in spite of himself, for such a bold, handsome, independent girl as Rosamund had never addressed him in such a way before; and, like all lads, he was susceptible to a girl's influence.

"I am at a horrid common school," he grumbled. "All the fellows there say horrid common things; but it is the best that poor old Em can afford, and I ought to be content. Some day I'll be a tradesman—not a gentleman. But now Aggie and I are both staying here with gentry of the first class in every way, and you say you'll be my friend even if I am a tradesman?"

"My hand on it," said Rosamund suddenly; and she held out her little white hand, which the boy grasped heartily.

"Now then," she continued, "I am going to tell you my story."

She did tell it, very simply, describing her influence from the very first over Irene, and contriving to put Irene's character into altogether a new light to the boy.

"There is the making of a splendid woman in her," she said; "but if you taunt her now you will undo all the good that I have done. Instead of doing this, suppose you take my place when I am away, and help Frosty not to be jealous, and help Irene and Agnes to enjoy themselves. Just show Irene that you are not a scrap afraid of her; but at the same time do not rouse her passions. Will you do this, and for my sake? If so, I do really believe all will be well."

Hughie was amazed at his own sensations.

"I declare," he said, "you'd turn any fellow into a brick. If there were more girls like you in the world I shouldn't be surprised if there were a lot of good men too; and the world could be oiled on all its hinges, so to speak, so that it wouldn't creak and jump and fret one at every turn as it seems to have an unpleasant habit of doing at the present moment."

"Will you promise, Hughie? I think you are the sort of boy who would keep your word at any and all times."

Hughie mumbled something that Rosamund took for a promise. In truth, he could not raise his eyes to her face, for they were full of tears, which he was ashamed to show.

"I wish you'd let me go away all by myself for a minute. I'll come back before lunch," he said. "You make a fellow feel like a gentleman, and that's the truth of it."

Then he dashed out of sight among the flowers.

Rosamund's last day at The Follies was spent in trying to soothe all parties. She tried to make Miss Frost rather less miserable. Hughie kept a good deal out of sight. Irene was so absorbed with Agnes—her new toy, as the servants called the little girl—that she did not even remember that Rosamund was to leave on the following day.

But when the next morning came, and she saw the carriage arrive at the door, and perceived Rosamund's trunks being put on the roof, she suddenly woke to the fact that the strong influence of her life during the last couple of months had come to a complete end; that Rosamund, the strong, the vivacious, the daring, the noble, was leaving her. All in a minute even little Agnes seemed distasteful to the excited girl. She flew up to Rosamund's side and flung her arms round her neck.

"Oh, you are going! You are going, and what is to become of me without you?"

Rosamund drew her into a little room leading out of the hall.

"Just one word, Irene," she said.

Comments (0)