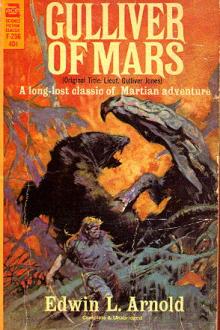

Gulliver of Mars by Edwin Lester Arnold (book recommendations based on other books txt) 📗

- Author: Edwin Lester Arnold

Book online «Gulliver of Mars by Edwin Lester Arnold (book recommendations based on other books txt) 📗». Author Edwin Lester Arnold

Covering Heru up and knowing well all our chances of escape lay in expedition, I went at once, in pursuance of a plan made during the night, to the good dame at what, for lack of a better name, must still continue to be called the fish-shop, and finding her alone, frankly told her the salient points of my story. When she learned I had "robbed the lion of his prey" and taken his new wife singlehanded from the dreaded Ar-hap her astonishment was unbounded. Nothing would do but she must look upon the princess, so back we went to the hiding-place, and when Heru knew that on this woman depended our lives she stepped ashore, taking the rugged Martian hand in her dainty fingers and begging her help so sweetly that my own heart was moved, and, thrusting hands in pocket, I went aside, leaving those two to settle it in their own female way.

And when I looked back in five minutes, royal Seth had her arms round the woman's neck, kissing the homely cheeks with more than imperial fervour, so I knew all was well thus far, and stopped expectorating at the little fishes in the water below and went over to them. It was time! We had hardly spoken together a minute when a couple of war-canoes filled with men appeared round the nearest promontory, coming down the swift water with arrow-like rapidity.

"Quick!" said the fishwife, "or we are all lost. Into your canoe and paddle up this creek. It runs out to the sea behind the town, and at the bar is my man's fishing-boat amongst many others. Lie hidden there till he comes if you value your lives." So in we got, and while that good Samaritan went back to her house we cautiously paddled through a deserted backwater to where it presently turned through low sandbanks to the gulf. There were the boats, and we hid the canoe and lay down amongst them till, soon after, a man, easily recognised as the husband of our friend, came sauntering down from the village.

At first he was sullen, not unreasonably alarmed at the danger into which his good woman was running him. But when he set eyes on Heru he softened immediately. Probably that thick-bodied fellow had never seen so much female loveliness in so small a bulk in all his life, and, being a man, he surrendered at discretion.

"In with you, then," he growled, "since I must needs risk my neck for a pair of runaways who better deserve to be hung than I do. In with you both into this fishing-cobble of mine, and I will cover you with nets while I go for a mast and sail, and mind you lie as still as logs. The town is already full of soldiers looking for you, and it will be short shrift for us all if you are seen."

Well aware of the fact and now in the hands of destiny, the princess and I lay down as bidden in the prow, and the man covered us lightly over with one of those fine meshed seines used by these people to catch the little fish I had breakfasted on more than once.

Materially I could have enjoyed the half-hour which followed, since such rest after exertion was welcome, the sun warm, the lapping of sea on shingle infinitely soothing, and, above all, Heru was in my arms! How sweet and childlike she was! I could feel her little heart beating through her scanty clothing, while every now and then she turned her gazelle eyes to mine with a trust and admiration infinitely alluring. Yes! as far as that went I could have lain there with that slip of maiden royalty for ever, but the fascination of the moment was marred by the thought of our danger. What was to prevent these new friends giving us away? They knew we had no money to recompense them for the risk they were running. They were poor, and a splendid reward, wealth itself to them, would doubtless be theirs if they betrayed us even by a look. Yet somehow I trusted them as I have trusted the poor before with the happiest results, and telling myself this and comforting Heru, I listened and waited.

Minute by minute went by. It seemed an age since the fisherman had gone, but presently the sound of voices interrupted the sea's murmur. Cautiously stealing a glance through a chink imagine my feelings on perceiving half a dozen of Ar-hap's soldiers coming down the beach straight towards us! Then my heart was bitter within me, and I tasted of defeat, even with Heru in my arms. Luckily even in that moment of agony I kept still, and another peep showed the men were now wandering about rather aimlessly. Perhaps after all they did not know of our nearness? Then they took to horseplay, as idle soldiers will even in Mars, pelting each other with bits of wood and dead fish, and thereon I breathed again.

Nearer they came and nearer, my heart beating fast as they strolled amongst the boats until they were actually "larking" round the one next to ours. A minute or two of this, and another footstep crunched on the pebbles, a quick, nervous one, which my instinct told me was that of our returning friend.

"Hullo old sprat-catcher! Going for a sail?" called out a soldier, and I knew that the group were all round our boat, Heru trembling so violently in my breast that I thought she would make the vessel shake.

"Yes," said the man gruffly.

"Let's go with him," cried several voices. "Here, old dried haddock, will you take us if we help haul your nets for you?"

"No, I won't. Your ugly faces would frighten all the fish out of the sea."

"And yours, you old chunk of dried mahogany, is meant to attract them no doubt."

"Let's tie him to a post and go fishing in his boat ourselves," some one suggested. Meanwhile two of them began rocking the cobble violently from side to side. This was awful, and every moment I expected the net and the sail which our friend had thrown down unceremoniously upon us would roll off.

"Oh, stop that," said the Martian, who was no doubt quite as well aware of the danger as we were. "The tide's full, the shoals are in the bay—stop your nonsense, and help me launch like good fellows."

"Well, take two of us, then. We will sit on this heap of nets as quiet as mice, and stand you a drink when we get back."

"No, not one of you," quoth the plucky fellow, "and here's my staff in my hand, and if you don't leave my gear alone I will crack some of your ugly heads."

"That's a pity," I thought to myself, "for if they take to fighting it will be six to one—long odds against our chances." There was indeed a scuffle, and then a yell of pain, as though a soldier had been hit across the knuckles; but in a minute the best disposed called out, "Oh, cease your fun, boys, and let the fellow get off if he wants to. You know the fleet will be down directly, and Ar-hap has promised something worth having to the man who can find that lost bit of crackling of his. It's my opinion she's in the town, and I for one would rather look for her than go haddock fishing any day."

"Right you are, mates," said our friend with visible relief. "And, what's more, if you help me launch this boat and then go to my missus and tell her what you've done, she'll understand, and give you the biggest pumpkinful of beer in the place. Ah, she will understand, and bless your soft hearts and heads while you drink it—she's a cute one is my missus."

"And aren't you afraid to leave her with us?"

"Not I, my daisy, unless it were that a sight of your pretty face might give her hysterics. Now lend a hand, your accursed chatter has already cost me half an hour of the best fishing time."

"In with you, old buck!" shouted the soldiers; I felt the fisherman step in, as a matter of fact he stepped in on to my toes; a dozen hands were on the gunwales: six soldier yells resounded, it seemed, in my very ears: there was the grit and rush of pebbles under the keel: a sudden lurch up of the bows, which brought the fairy lady's honey-scented lips to mine, and then the gentle lapping of deep blue waters underneath us!

There is little more to be said of that voyage. We pulled until out of sight of the town, then hoisted sail, and, with a fair wind, held upon one tack until we made an island where there was a small colony of Hither folk.

Here our friend turned back. I gave him another gold button from my coat, and the princess a kiss upon either cheek, which he seemed to like even more than the button. It was small payment, but the best we had. Doubtless he got safely home, and I can but hope that Providence somehow or other paid him and his wife for a good deed bravely done.

Those islanders in turn lent us another boat, with a guide, who had business in the Hither capital, and on the evening of the second day, the direct route being very short in comparison, we were under the crumbling marble walls of Seth.

CHAPTER XX

It was like turning into a hothouse from a keen winter walk, our arrival at the beautiful but nerveless city after my life amongst the woodmen.

As for the people, they were delighted to have their princess back, but with the delight of children, fawning about her, singing, clapping hands, yet asking no questions as to where she had been, showing no appreciation of our adventures—a serious offence in my eyes—and, perhaps most important of all, no understanding of what I may call the political bearings of Heru's restoration, and how far their arch enemies beyond the sea might be inclined to attempt her recovery.

They were just delighted to have the princess back, and that was the end of it. Theirs was the joy of a vast nursery let loose. Flower processions were organised, garlands woven by the mile, a general order issued that the nation might stay up for an hour after bedtime, and in the vortex of that gentle rejoicing Heru was taken from me, and I saw her no more, till there happened the wildest scene of all you have shared with me so patiently.

Overlooked, unthanked, I turned sulky, and when this mood, one I can never maintain for long, wore off, I threw myself into the dissipation about me with angry zeal. I am frankly ashamed of the confession, but I was "a sailor ashore," and can only claim the indulgences proper to the situation. I laughed, danced, drank, through the night; I drank deep of a dozen rosy ways to forgetfulness, till my mind was a great confusion, full of flitting pictures of loveliness, till life itself was an illusive pantomime, and my will but thistle-down on the folly of the moment. I drank with those gentle roisterers all through their starlit night, and if we stopped when morning came it was more from weariness than virtue. Then the yellow-robed slaves gave us the wine of recovery—alas! my faithful An was not amongst them—and all through the day we lay about in sodden happiness.

Towards nightfall I was myself again, not unfortunately with the headache well earned, but sufficiently remorseful to be in a vein to make good resolutions for the future.

In this mood I mingled with a happy crowd, all purposeless and cheerful as usual, but before long began to feel the influence of one of those drifts, a universal turning in one direction, as seaweed turns when the tide changes, so characteristic of Martian society. It was dusk, a lovely soft velvet dusk, but not dark yet, and I said to a yellow-robed fairy at my side:

"Whither away, comrade? It is not eight bells yet. Surely we are not going to be put to bed so early as this?"

"No," said that smiling individual, "it is the princess. We are going to listen to Princess Heru in the palace square.

Comments (0)