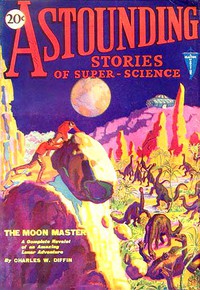

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 by Various (best books to read ever .txt) 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 by Various (best books to read ever .txt) 📗». Author Various

Bell's face was cold and hard is if carved from marble.

"I haven't lived through it," said the white man harshly, "by being soft. And I've got less than no time to live—sane, anyhow. I was thinking of shooting you in the back, because the young lady—"

He laughed as Bell's revolver muzzle stirred.

"I'm telling you," said the white man in ghastly merriment, "because I thought—I thought One-Fourteen had set me the example of ditching the Service for his own life. But now it's different."

He pointed.

"There's a launch in that house, with one of these outboard motors. It was used to keep up communication with the boat gangs that sweat the heavy supplies up the river. It'll float in three inches of water, and you can pole it where the water's too shallow to let the propeller turn. This rabble will mob you if you try to take it, because it'll have taken them just about this long to realize that they're deserted. They'll think you are a deputy, at least, to have dared release me. I'm going to convince them of it, and use this gun to give you a start. I give you two hours. It ought to be enough. And then...."

Bell nodded.

"I'm not Service," he said curtly, "but I'll see it's known."

The white man laughed again.

"'Some sigh for the glories of this world, and some for a prophet's paradise to come,'" he quoted derisively. "I thought I was hard, Bell, but I find I prefer to have my record clean in the Service—where nobody will ever see it—than to take what pleasure I might snatch before I die. Queer, isn't it? Old Omar was wrong. Now watch me bluff, flinging away the cash for credit of doubtful value, and all for the rumble of a distant drum—which will be muted!"

They were surrounded by swarming, fawning, frightened camaradas who implored the Senhor to tell them if he were a deputy of The Master, and if he were here to make sure nothing evil befell them. They worked for The Master, and they desired nothing save to labor all their lives for The Master, only—only—The Master would allow no evil to befall them?

The white man waved his arms grandiloquently.

"The Senhor you behold," he proclaimed in the barbarous Portugese of the hinterland of Brazil, "has released me from the cage in which you saw me. He is the deputy of The Master himself, and is enraged because the landing lights on the field were not burning, so that his airplane fell down[Pg 110] into the jungle. He bears news of great value from me to The Master, which will make me finally a sub-deputy of The Master. And I have a revolver, as you see, with which I could kill him, but he dares not permit me to die, since I have given him news for The Master. I shall wait here and he will go and send back an airplane with the grace of The Master for me and for all of you."

Bell snarled an assent, in the arrogant fashion of the deputies of The Master. He waited furiously while the Service man argued eloquently and fluently. He fingered his revolver suggestively when a wave of panic swept over the swarming mob for no especial reason. And then he watched grimly while the light little metal-bottomed boat was carried to the water's edge and loaded with food, and fuel, and arms, and ammunition, and even mosquito bars.

The white man grinned queerly at Bell as he extended his hand in a last handshake.

"'I, who am about to die, salute you!'" he said mockingly. "Isn't this a hell of a world, Bell? I'm sure we could design a better one in some ways."

Bell felt a horrible, a ghastly shock. The hand that gripped his was writhing in his grasp.

"Quite so," said the white man. "It started about five minutes ago. In theory, I've about forty-eight hours. Actually, I don't dare wait that long, if I'm to die like a white man. And a lingering vanity insists on that. I hope you get out, Bell.... And if you want to do me a favor,"—he grinned again, mirthlessly—"you might see that The Master and as many of his deputies as you can manage join me in hell at the earliest possible moment. I shan't mind so much if I can watch them."

He put his hands quickly in his pockets as the little outboard motor caught and the launch went on down-river. He did not even look after them. The last Bell saw of him he was swaggering back up the little hillside above the river edge, surrounded by scared inhabitants of the workmen's shacks, and scoffing in a superior fashion at their fears.

CHAPTER XIIIt took Bell just eight days to reach the Paraguay, and those eight days were like an age-long nightmare of toil and discomfort and more than a little danger. The launch was headed downstream, of course, and with the current behind it, it made good time. But the distances of Brazil are infinite, and the jungles of Brazil are malevolent, and the route down the Rio Laurenço was designed by the architect of hell. Raudales lay in wait to destroy the little boat. Insects swarmed about to destroy its voyagers. And the jungle loomed above them, passively malignant, and waited for them to die.

And as if physical sufferings were not enough, Bell saw Paula wilt and grow pale. All the way down the river they passed little clearings at nearly equal distances. And men came trembling out of the little houses upon those fazendas and fawned upon the Senhor who was in the launch that had come from up-river and so must be in the service of The Master himself. The clearings and the tiny houses had been placed upon the river for the service of the terribly laboring boat gangs who brought the heavier supplies up the river to The Master's central depot. Men at these clearings had been enslaved and ordered to remain at their posts, serving all those upon the business of The Master. They fawned abjectly upon Bell, because he was of os gentes and so presumably was empowered, as The Master had empowered his more intelligent subjects, to exact the most degraded of submission from all beneath him in the horrible conspiracy. Once, indeed, Bell was humbly implored by a panic stricken man to administer "the grace of The Master" to[Pg 111] a moody and irritable child of twelve or so.

"She sees the red spots, Senhor. It is the first sign. And I have served The Master faithfully...."

And Bell could do nothing. He went on savagely. And once he passed a gang of camaradas laboring to get heavily loaded dugouts up a fiendish raudal. They had ropes out and were hauling at them from the bank, while some of their number were breast-deep in the rushing water, pushing the dugouts against the stream.

"They're headed for the plantation," said Bell grimly, "and they'll need the grace of The Master by the time they get there. And it's abandoned. But if I tell them...."

Men with no hope at all are not to be trusted. Not when they are mixtures of three or more races—white and black and red—and steeped in ignorance and superstition and, moreover, long subject to such masters as these men had had. Bell had to think of Paula.

He could have landed and haughtily ordered them to float or even carry the light boat to the calmer waters below. They would have obeyed and cringed before him. But he shot the rapids from above, with the little motor roaring past rocks and walls of jungle beside the foaming water, at a speed that chilled his blood.

Paula said nothing. She was white and listless. Bell, himself, was being preyed upon by a bitter blend of horror and a deep-seated rage that consumed him like a fever. He had fever itself, of course. He was taking, and forcing Paula to take, five grains of quinine a day. It had been included among his stores as a matter of course by those who had loaded his boat. And with the fever working in his brain he found himself holding long, imaginary conversations, in which one part of his brain reproached the other part for having destroyed the plantation of The Master. The laborers upon that plantation had been abandoned to the murder madness because of his deed. The caretakers of the tiny fazenda on the river bank were now ignored. Bell felt himself a murderer because he had caused The Master's deputies to cast them off in a callous indifference to their inevitable fate.

He suffered the tortures of the damned, and grew morose and bitter, and could only escape that self torture by coddling his hatred of Ribiera and The Master. He imagined torments to be inflicted upon them which would adequately repay them for their crimes, and racked his feverish brain for memories of the appalling atrocities which can be committed upon the human body without destroying its capacity to suffer.

It was not normal. It was not sane. But it filled Bell's mind and somehow kept him from suicide during the horrible passage of the river. He hardly dared speak to Paula. There was a time when he counted the days since he had been a guest at Ribiera's estate outside of Rio, and frenziedly persuaded himself that he saw red spots before his eyes and soon would have the murder madness come upon him. And then he thought of the supplies in Ribiera's plane, in which they had escaped from Rio. They had eaten that food.

It was almost unconsciously, then, that he saw the narrow water on which the launch floated valiantly grow wider day by day. When at last it debouched suddenly into a vast stream whereon a clumsy steamer plied beneath a self made cloud of smoke, he stared dully at it for minutes before he realized.

"Paula," he said suddenly, and listened in amazement to his voice. It was hoarse and harsh and croaking. "Paula, we've made it. This must be the Paraguay."

She roused herself and looked about like a person waking from a lethargic sleep. And then her lips quivered, and[Pg 112] she tried to speak and could not, and tears fell silently from her eyes, and all at once she was sobbing bitterly.

That sign of the terrific strain she had been under served more than anything else to jolt Bell out of his abnormal state of mind. He moved over to her and clumsily put his arm about her, and comforted her as best he could. And she sat sobbing with her head on his shoulder, gasping in a form of hysterical relief, until the engine behind them sputtered, and coughed, and died.

When Bell looked, the last drop of gasoline was gone. But the motor had served its purpose. It had run manfully on an almost infinitesimal consumption of gasoline for eight days. It had not missed an explosion save when its wiring was wetted by spray. And now....

Bell hauled the engine inboard and got out the oars from under the seats. He got the little boat out to mid-stream, and they floated down until a village of squalid huts appeared on the eastern bank. He landed, there, and with much bargaining and a haughty demeanor disposed of the boat to the skipper of a batelao in exchange for passage down-river as far as Corumba. The rate was outrageously high. But he had little currency with him and dared go no farther on a vessel which carried a boat of The Master's ownership conspicuously towed behind.

At Corumba he purchased clothes less obviously of os gentes, both for himself and for Paula, and that same afternoon was able to arrange for their passage to Asunción as deck passengers on a river steamer going downstream.

It was as two peasants, then, that they rode in sweltering heat amid a swarming and odorous mass of fellow humanity downstream. But it was a curious relief, in some ways. The people about them were gross and unwashed and stupid, but they were human. There was none of that diabolical feeling of terror all about. There were no strained, fear haunted faces upon the deck

Comments (0)