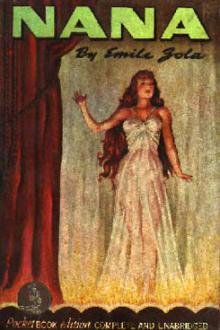

Nana - Émile Zola (good books to read for young adults txt) 📗

- Author: Émile Zola

- Performer: -

Book online «Nana - Émile Zola (good books to read for young adults txt) 📗». Author Émile Zola

fairyland!”

Zoe went up, grumbling. On the roof she found her mistress leaning

against the brickwork balustrade and gazing at the valley which

spread out into the silence. The horizon was immeasurably wide, but

it was now covered by masses of gray vapor, and a fierce wind was

driving fine rain before it. Nana had to hold her hat on with both

hands to keep it from being blown away while her petticoats streamed

out behind her, flapping like a flag.

“Not if I know it!” said Zoe, drawing her head in at once. “Madame

will be blown away. What beastly weather!”

Madame did not hear what she said. With her head over the

balustrade she was gazing at the grounds beneath. They consisted of

seven or eight acres of land enclosed within a wall. Then the view

of the kitchen garden entirely engrossed her attention. She darted

back, jostling the lady’s maid at the top of the stairs and bursting

out:

“It’s full of cabbages! Oh, such woppers! And lettuces and sorrel

and onions and everything! Come along, make haste!”

The rain was falling more heavily now, and she opened her white silk

sunshade and ran down the garden walks.

“Madame will catch cold,” cried Zoe, who had stayed quietly behind

under the awning over the garden door.

But Madame wanted to see things, and at each new discovery there was

a burst of wonderment.

“Zoe, here’s spinach! Do come. Oh, look at the artichokes! They

are funny. So they grow in the ground, do they? Now, what can that

be? I don’t know it. Do come, Zoe, perhaps you know.”

The lady’s maid never budged an inch. Madame must really be raving

mad. For now the rain was coming down in torrents, and the little

white silk sunshade was already dark with it. Nor did it shelter

Madame, whose skirts were wringing wet. But that didn’t put her out

in the smallest degree, and in the pouring rain she visited the

kitchen garden and the orchard, stopping in front of every fruit

tree and bending over every bed of vegetables. Then she ran and

looked down the well and lifted up a frame to see what was

underneath it and was lost in the contemplation of a huge pumpkin.

She wanted to go along every single garden walk and to take

immediate possession of all the things she had been wont to dream of

in the old days, when she was a slipshod workgirl on the Paris

pavements. The rain redoubled, but she never heeded it and was only

miserable at the thought that the daylight was fading. She could

not see clearly now and touched things with her fingers to find out

what they were. Suddenly in the twilight she caught sight of a bed

of strawberries, and all that was childish in her awoke.

“Strawberries! Strawberries! There are some here; I can feel them.

A plate, Zoe! Come and pick strawberries.”

And dropping her sunshade, Nana crouched down in the mire under the

full force of the downpour. With drenched hands she began gathering

the fruit among the leaves. But Zoe in the meantime brought no

plate, and when the young woman rose to her feet again she was

frightened. She thought she had seen a shadow close to her.

“It’s some beast!” she screamed.

But she stood rooted to the path in utter amazement. It was a man,

and she recognized him.

“Gracious me, it’s Baby! What ARE you doing there, baby?”

“‘Gad, I’ve come—that’s all!” replied Georges.

Her head swam.

“You knew I’d come through the gardener telling you? Oh, that poor

child! Why, he’s soaking!”

“Oh, I’ll explain that to you! The rain caught me on my way here,

and then, as I didn’t wish to go upstream as far as Gumieres, I

crossed the Choue and fell into a blessed hole.”

Nana forgot the strawberries forthwith. She was trembling and full

of pity. That poor dear Zizi in a hole full of water! And she drew

him with her in the direction of the house and spoke of making up a

roaring fire.

“You know,” he murmured, stopping her among the shadows, “I was in

hiding because I was afraid of being scolded, like in Paris, when I

come and see you and you’re not expecting me.”

She made no reply but burst out laughing and gave him a kiss on the

forehead. Up till today she had always treated him like a naughty

urchin, never taking his declarations seriously and amusing herself

at his expense as though he were a little man of no consequence

whatever. There was much ado to install him in the house. She

absolutely insisted on the fire being lit in her bedroom, as being

the most comfortable place for his reception. Georges had not

surprised Zoe, who was used to all kinds of encounters, but the

gardener, who brought the wood upstairs, was greatly nonplused at

sight of this dripping gentleman to whom he was certain he had not

opened the front door. He was, however, dismissed, as he was no

longer wanted.

A lamp lit up the room, and the fire burned with a great bright

flame.

“He’ll never get dry, and he’ll catch cold,” said Nana, seeing

Georges beginning to shiver.

And there were no men’s trousers in her house! She was on the point

of calling the gardener back when an idea struck her. Zoe, who was

unpacking the trunks in the dressing room, brought her mistress a

change of underwear, consisting of a shift and some petticoats with

a dressing jacket.

“Oh, that’s first rate!” cried the young woman. “Zizi can put ‘em

all on. You’re not angry with me, eh? When your clothes are dry

you can put them on again, and then off with you, as fast as fast

can be, so as not to have a scolding from your mamma. Make haste!

I’m going to change my things, too, in the dressing room.”

Ten minutes afterward, when she reappeared in a tea gown, she

clasped her hands in a perfect ecstasy.

“Oh, the darling! How sweet he looks dressed like a little woman!”

He had simply slipped on a long nightgown with an insertion front, a

pair of worked drawers and the dressing jacket, which was a long

cambric garment trimmed with lace. Thus attired and with his

delicate young arms showing and his bright damp hair falling almost

to his shoulders, he looked just like a girl.

“Why, he’s as slim as I am!” said Nana, putting her arm round his

waist. “Zoe, just come here and see how it suits him. It’s made

for him, eh? All except the bodice part, which is too large. He

hasn’t got as much as I have, poor, dear Zizi!”

“Oh, to be sure, I’m a bit wanting there,” murmured Georges with a

smile.

All three grew very merry about it. Nana had set to work buttoning

the dressing jacket from top to bottom so as to make him quite

decent. Then she turned him round as though he were a doll, gave

him little thumps, made the skirt stand well out behind. After

which she asked him questions. Was he comfortable? Did he feel

warm? Zounds, yes, he was comfortable! Nothing fitted more closely

and warmly than a woman’s shift; had he been able, he would always

have worn one. He moved round and about therein, delighted with the

fine linen and the soft touch of that unmanly garment, in the folds

of which he thought he discovered some of Nana’s own warm life.

Meanwhile Zoe had taken the soaked clothes down to the kitchen in

order to dry them as quickly as possible in front of a vine-branch

fire. Then Georges, as he lounged in an easy chair, ventured to

make a confession.

“I say, are you going to feed this evening? I’m dying of hunger. I

haven’t dined.”

Nana was vexed. The great silly thing to go sloping off from

Mamma’s with an empty stomach, just to chuck himself into a hole

full of water! But she was as hungry as a hunter too. They

certainly must feed! Only they would have to eat what they could

get. Whereupon a round table was rolled up in front of the fire,

and the queerest of dinners was improvised thereon. Zoe ran down to

the gardener’s, he having cooked a mess of cabbage soup in case

Madame should not dine at Orleans before her arrival. Madame,

indeed, had forgotten to tell him what he was to get ready in the

letter she had sent him. Fortunately the cellar was well furnished.

Accordingly they had cabbage soup, followed by a piece of bacon.

Then Nana rummaged in her handbag and found quite a heap of

provisions which she had taken the precaution of stuffing into it.

There was a Strasbourg pate, for instance, and a bag of sweetmeats

and some oranges. So they both ate away like ogres and, while they

satisfied their healthy young appetites, treated one another with

easy good fellowship. Nana kept calling Georges “dear old girl,” a

form of address which struck her as at once tender and familiar. At

dessert, in order not to give Zoe any more trouble, they used the

same spoon turn and turn about while demolishing a pot of preserves

they had discovered at the top of a cupboard.

“Oh, you dear old girl!” said Nana, pushing back the round table.

“I haven’t made such a good dinner these ten years past!”

Yet it was growing late, and she wanted to send her boy off for fear

he should be suspected of all sorts of things. But he kept

declaring that he had plenty of time to spare. For the matter of

that, his clothes were not drying well, and Zoe averred that it

would take an hour longer at least, and as she was dropping with

sleep after the fatigues of the journey, they sent her off to bed.

After which they were alone in the silent house.

It was a very charming evening. The fire was dying out amid glowing

embers, and in the great blue room, where Zoe had made up the bed

before going upstairs, the air felt a little oppressive. Nana,

overcome by the heavy warmth, got up to open the window for a few

minutes, and as she did so she uttered a little cry.

“Great heavens, how beautiful it is! Look, dear old girl!”

Georges had come up, and as though the window bar had not been

sufficiently wide, he put his arm round Nana’s waist and rested his

head against her shoulder. The weather had undergone a brisk

change: the skies were clearing, and a full moon lit up the country

with its golden disk of light. A sovereign quiet reigned over the

valley. It seemed wider and larger as it opened on the immense

distances of the plain, where the trees loomed like little shadowy

islands amid a shining and waveless lake. And Nana grew

tenderhearted, felt herself a child again. Most surely she had

dreamed of nights like this at an epoch which she could not recall.

Since leaving the train every object of sensation—the wide

countryside, the green things with their pungent scents, the house,

the vegetables—had stirred her to such a degree that now it seemed

to her as if she had left Paris twenty years ago. Yesterday’s

existence was far, far away, and she was full of sensations of which

she had no previous experience. Georges, meanwhile, was giving her

neck little coaxing kisses, and this again added to her sweet

unrest. With hesitating hand she pushed him from

Comments (0)