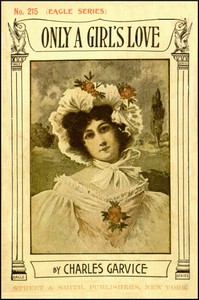

Only a Girl's Love by Charles Garvice (best contemporary novels .TXT) 📗

- Author: Charles Garvice

Book online «Only a Girl's Love by Charles Garvice (best contemporary novels .TXT) 📗». Author Charles Garvice

He would have drawn her close to him, but she shrank back with a little frightened gesture.

"Come," he said, and he drew her gently toward the boat.

Stella hesitated.

"Suppose," she said, "someone saw us," and the color flew to her face.

[129]

"And if!" he retorted, with a sudden look of defiance, which melted in a moment. "There is no fear of that, my darling; we will go down the back water. Come."

There was no resisting that low-voiced mingling of entreaty and loving command. With the tenderest care he helped her into the boat and arranged the cushion for her.

"See," he said, "if we meet any boat you must put up your sunshade, but we shall not where we are going."

Stella leant back and watched him under her lowered lids as he rowed—every stroke of the strong arm sending the boat along like an arrow from the bow—and an exquisite happiness fell upon her. She did not want him to speak; it was enough for her to sit and watch him, to know that he was within reach of her hand if she bent forward, to feel that he loved her.

He rowed down stream until they came to an island; then he guided the boat out of the principal current into a back water, and rested on his oars.

"Now let me look at you!" he said. "I haven't had an opportunity yet."

Stella put up her sunshade to shield her face, and laughingly he drew it away.

"That is not fair. I have been thirsting for a glance from those dark eyes all day. I cannot have them hidden now. And what are you thinking of?" he asked, smilingly, but with suppressed eagerness, "There is a serious little look in those eyes of yours—of mine! They are mine, are they not, Stella? What is it?"

"Shall I tell you?" she answered, in a low voice.

"Yes," he said. "You shall whisper it. Let me come nearer to you," and he sank down at her feet and put up his hand for hers. "Now then."

Stella hesitated a moment.

"I was thinking and wondering whether this—whether this isn't very wrong, Le—Leycester."

The name dropped almost inaudibly, but he heard it and put her hand to his lips.

"Wrong?" he said, as if he were weighing the question most judiciously. "Yes and no. Yes, if we do not love each other, we two. No, if we do. I can speak for myself, Stella. My conscience is at rest because I love you. And you?"

Her hand closed in his.

"No, my darling," he said, "I would not ask you to do anything wrong. It may be a little unconventional, this stolen half-hour of ours—perhaps it is; but what do you and I care for the conventional? It is our happiness we care for," and he smiled up at her.

It was a dangerously subtle argument for a girl of nineteen, and coming from the man she loved, but it sufficed for Stella, who scarcely knew the full meaning of the term "conventional," but, nevertheless, she looked down at him with a serious light in her eye.

"I wonder if Lady Lenore would have done it," she said.

A cloud like a summer fleece swept across his face.

[130]

"Lenore?" he said, then he laughed. "Lenore and you are two very different persons, thank Heaven. Lenore," and he laughed, "worships the conventional! She would not move a step in any direction excepting that properly mapped out by Mrs. Grundy."

"You would not ask her, then?" said Stella.

He smiled.

"No, I should not," he said, emphatically and significantly. "I should not ask anyone but you, my darling. Would you wish me to?"

"No, no," she said hastily, and she laughed.

"Then let us be happy," he said, caressing her hand. "Do you know that you have made a conquest—I mean in addition to myself?"

"No," she said. "I?"

"Yes, you," he repeated. "I mean my sister Lilian."

"Ah!" said Stella, with a little glad light in her eyes. "How beautiful and lovable she is!"

He nodded.

"Yes, and she has fallen in love with you. We are very much alike in our tastes," he said, with a significant smile. "Yes, she thinks you beautiful and lovable."

Stella looked down at the ardent face, so handsome in its passionate eagerness.

"Did you—did you tell her?" she murmured.

He understood what she meant, and shook his head.

"No; it was to be a secret—our secret for the present, my darling. I did not tell her."

"She would be sorry," said Stella. "They would all be sorry, would they not?" she added, sadly.

"Why should you think of that?" he expostulated, gently. "What does it matter? All will come right in the end. They will not be sorry when you are my wife. When is it to be, Stella?" and his voice grew thrillingly soft.

Stella started, and a scarlet blush flushed her face.

"Ah, no!" she said, almost pantingly, "not for very, very long—perhaps never!"

"It must be very soon," he murmured, putting his arm around her. "I could not wait long! I could not endure existence if we should chance to be parted. Stella, I never knew what love meant until now! If you knew how I have waited for this meeting of ours, how the weary hours have hung with leaden weight upon my hands, how miserably dull the day seemed, you would understand."

"Perhaps I do," she said softly, and the dark eyes dwelt upon his musingly as she recalled her own listlessness and impatience.

"Then you must think as I do!" he said, quick to take advantage. "Say you do, Stella! Think how very happy we should be."

She did think, and the thought made her tremble with excess of joy.

"We two together in the world! Where we would go and what we would do! We could go to all the beautiful places—your[131] own Italy, Switzerland! and always together—think of it."

"I am thinking," she said with a smile.

He drew closer and put her arm around his neck. The very innocence and purity of her love inflamed his passion and enhanced her charms in his sight.

He had been loved before, but never like this, with such perfect, unquestioning love.

"Well, then, my darling, why should we wait? It must be soon, Stella."

"No, no," she said, faintly. "Why should it? I—I am very happy."

"What is it you dread? Is it so dreadful the thought that we should be alone together—all in all to each other?"

"It is not that," said Stella, her eyes fixed on the line of light that fell on the water from the rising moon. "It is not that. I am thinking of others."

"Always of others!" he said, with tender reproach. "Think of me—of ourselves."

"I wish——" she said.

"Wish," he coaxed her. "See if I cannot gratify it. I will, if it be possible."

"It is not possible," she said. "I was going to say that I wish you were not—what you are."

"You said something like that last night," he said. "Darling, I have wished it often. You wish that I were plain Mr. Brown."

"No, no," she said, with a smile; "not that."

"That I were a Mr. Wyndward——"

"With no castle," she broke in. "Ah, if that could be! If you were only, say, a workman! How good that would be! Think! you would live in a little cottage, and you would go to work, and come home at night, and I should be waiting for you with your tea—do they have tea or dinner?" she broke off to inquire, with a laugh.

"You see," he said, returning her laugh, "it would not do. Why, Stella, you were not made for a workman's wife; the sordid cares of poverty are for different natures to yours. And yet we should be happy, we two." And he sighed wistfully. "You would be glad to see me come home, Stella?"

"Yes," she said, half seriously, half archly. "I have seen them in Italy, the peasants' wives, standing at the cottage doors, the hot sunset lighting up their faces and their colored kerchiefs, waiting for their husbands, and watching them as they climbed the hills from the pastures and the vineyards, and they have looked so happy that I—I have envied them. I was not happy in Italy, you know."

"My Stella!" he murmured. His love for her was so deep and passionate, his sympathy so keen that half phrases were as plainly understood by him as if she had spoken for hours. "And so you would wait for me at some cottage door?" he said. "Well, it shall be so. I will leave England, if you like—leave the castle and take some little ivy-green cottage."

She smiled, and shook her head.

"Then they would have reason to complain," she said; "they[132] would say 'she has dragged him down to her level—she has taught him to forget all the duties of his rank and high position—she has'—what is it Tennyson says—'robbed him of all the uses of life, and left him worthless.'"

Lord Leycester looked up at the exquisite face with a new light of admiration.

This was no mere pretty doll, no mere bread-and-butter school-girl to whom he had given his love, but a girl who thought, and who could express her thoughts.

"Stella!" he murmured, "you almost frighten me with your wisdom. Where did you learn such experience? Well, it is not to be a cottage, then; and I am not to work in the fields or tend the sheep. What then remains? Nothing, save that you take your proper place in the world as my wife;" the indescribable tenderness with which he whispered the last word brought the warm blood to her face. "Where should I find a lovelier face to add to the line of portraits in the old hall? Where should I find a more graceful form to stand by my side and welcome my guests? Where a more 'gracious ladye' than the maiden I love?"

"Oh, hush! hush!" whispered Stella, her heart beating beneath the exquisite pleasure of his words, and the gently passionate voice in which they were spoken. "I am nothing but a simple, stupid girl, who knows nothing except——" she stopped.

"Except!" he pressed her.

She looked at the water a moment, then she bent down, and lightly touched his hand with her lips.

"Except that she loves you!"

It was all summed up in this. He did not attempt to return the caress; he took it reverentially, half overwhelmed with it. It was as if a sudden stillness had fallen on nature, as if the night stood still in awe of her great happiness.

They were silent for a minute, both wrapped in thoughts of the other, then Stella said suddenly, and with a little not-to-be-suppressed sigh:

"I must go! See, the moon is almost above the trees."

"It rises early to-night, very," he said, eagerly.

"But I must go," she said.

"Wait a moment," he pleaded. "Let us go on shore and walk to the weir—only to the weir; then we will come back and I will row you over. It will not take five minutes! Come, I want to show it to you with the moon on it. It is a favorite spot of mine; I have often stood and watched it as the water danced over it in the moonlight. I want to do so this evening, with you by my side. I am selfish, am I not?"

He helped her out of the boat, almost taking her in his arms, and touching her sleeve with his lips; in his chivalrous mood he would not so far take advantage of her in her helplessness as to kiss her face, and they walked hand in hand, as they used to do in the good old days when men and women were not ashamed of love.

Why is it that they should be now? Why is it that when a pair of lovers indulge on the stage in the most chaste of embraces, a snigger and a grin run through the audience? In this age of[133] burlesque and satire, of sarcasm and cynicism, is there to be no love making? If so, what are poets and novelists to write about—the electric light and the science of astronomy?

They walked hand in hand, Leycester Wyndward Viscount Trevor, heir to Wyndward and an earldom, and Stella, the painter's niece, and threaded the wood, keeping well under the shadows of the high trees, until they reached the bank where the weir touched.

Lord Leycester took her to the brink and held her lightly.

"See," he said, pointing to the silver stream of water; "isn't that beautiful; but it is not for its beauty only that I have brought you to the river. Stella, I want you to plight your troth to me here."

"Here?" she said, looking up at his eager face.

"Yes; this spot is reported haunted—haunted by good fairies instead of evil spirits. We will ask them to smile on our betrothal, Stella."

She smiled, and watched his eyes with

Comments (0)