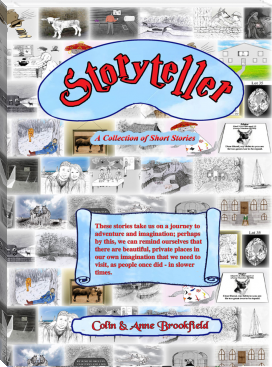

Storyteller - Colin & Anne Brookfield (ebook and pdf reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Colin & Anne Brookfield

Book online «Storyteller - Colin & Anne Brookfield (ebook and pdf reader .txt) 📗». Author Colin & Anne Brookfield

Although it felt intrusive, I had found it necessary to open the folded letter of Charlie’s that I had kept with the other note, which was on headed paper. It was addressed to his sister Daphne, at Walsham Estate, Walsham Village, Shropshire, England. In the letter, Charlie asked if they would accept his wife back into the family, as ‘she has done no wrong for us to have so ill-treated her’.

As an Italian prisoner of war in a far off country, I had no idea if, or how, I could fulfil my promise to Charlie but then fate intervened. We were to be shipped to Britain.

At first, we spent a few weeks at an old race course in Middlesex, and from there, to a large internment camp in a place called ‘Shropshire’.

Eddie’s life had now settled down to camp routines; it was morning and he was sharpening his razor on the hanging leather strop nearby, ready to shave.

“You’ll go to work without any breakfast if you don’t get down to the mess hall bloody quick,” barked the military police sergeant. “And I don’t want to see you feeding that pet rat of yours in the mess hall anymore, you’ll give your mates the plague.”

Henry, who was in Eddie’s pocket could hear that, and wasn’t too pleased about it.

Within the hour breakfast was over, and Eddie was standing to attention with three hundred others on the camp parade ground, overseen by the sergeant outside the Commanding Officer’s office.

It was from here they were daily allocated in small groups to outlying Shropshire farms as agricultural workers. Eddie’s group clambered into the back of the three ton Bedford vehicle and they were on their way to their place of work at Harvey’s Farm.

There was the usual hearty welcome on their arrival.

“Good morning lads,” said Martha Parish, the farm owner. “I see you’ve brought some good weather with you again, so perhaps we can harvest the dried hay from the top fields and bring it back to the barn.”

Martha seemed to have taken a shine to Eddie. He had been told by one of the land girls that he had a likeness to Martha’s son, who was serving his country abroad. He was allocated the job of driving the horse drawn hay cart for the next few days, so the other prisoners teasingly called him, ‘Mummy’s little favourite’.

Eddie’s job was a bit of a joke. Ned the draft horse knew the way from the fields and barn as intimately as his own reflection in the farm water trough, and was therefore probably having a private smirk at humans.

Before the work began, Martha drew Eddie aside from the others. She looked at him and frowned.

“Not planning anything are we?” she enquired. “You have been asking questions about local villages, places and people. Moreover, you borrowed a local map from one of the land girls.”

“No Martha, I’m not planning to escape, I promise.”

“Well, don’t worry, I won’t report this; just don’t do anything silly. If you do run, they’ll shoot to kill and that would upset me very much.”

From inside Eddie’s pocket, Henry was making a mental note of all these conversations, and it was helpful to him that Eddie was an ongoing chatterbox to himself in English, as it was his way of perfecting the language. The camp military police referred to him as, ‘soliloquising Eddie’. Although Henry was used to the chattering by now, it nevertheless made the horse’s ears pay constant attention, in case there was an instruction in there somewhere.

Whilst Eddie continued to rattle on quietly to himself, he withdrew three items from inside his coat for perusal. At the same time, an inquisitive pair of sharp eyes peered out from Eddie’s pocket. The first item revealed a small photograph of an attractive young woman, on the back of which, was written, ‘From your devoted wife Margaret’.

The next item was only glanced at. It was a small sheet of expensive notepaper, headed with a foreign family crest.

Finally, there was a letter written to a local address and signed, ‘Charles Phillips’.

All the pieces started to come together in Henry’s mercurial mind. He realised that Charles Phillips was none other than Charlie, the dying soldier on the battlefield, and that there was a game afoot if he wasn’t mistaken.

At the end of the working day, the prisoners collected in the farmyard awaiting their transport back to the camp. As Eddie was the last to arrive, he slipped into the barn so that he could conceal the documents.

The following morning the shire was in an uproar; a prisoner had escaped from the camp during the night. It was therefore no surprise to Martha Parish when the usual delivery of prisoners to her farm did not include Eddie, and more to the point, some old clothes ready for disposal had also disappeared from an outhouse.

Eddie had known exactly where he was going and the sergeant’s ‘borrowed’ bicycle was getting him there fast. The parting words of the young British soldier Charlie Phillips, were still in his mind. ‘When the war is over, please try and contact Daphne Phillips at Walsham Estate in Shropshire, but don’t give her anything, and don’t trust her. Regrettably, she is the only one who knows the whereabouts of my wife, to whom my private papers must go .... and NOBODY else.’

The great Walsham Manor was easy to find, Eddie only had to follow the river Severn that led right on through the estate farmlands. It was scarcely after midnight when he quietly laid the sergeant’s bicycle to rest in an outhouse on the Phillips’ estate, and then found a hidden place to sleep away the remaining nocturnal hours.

It was much later than intended when he finally awoke; the sun had already reached high in the sky and he was feeling quite nervous. He had chosen his position for the clear view it offered to the front of the manor, and from where he could now see the gardeners at work on the flowerbeds. He would have to wait until their ministering was completed, but it suited Henry, as it allowed time for Eddie to feed him.

When the last of the gardeners had finally trundled their wheelbarrows out of sight, Eddie made his move and Henry jumped back into his pocket. The front entry to the manor was preceded by an enormous jutting portico over its Romanesque support pillars. He was scarcely up the last of the steps to the threshold, when the door swung open and a haughty, suspicious looking doorman enquired about his business.

“It’s a family matter,” Eddie stated with authority in his best practiced English. He was led reluctantly through to a waiting room.

He heard the sounds of voices and scuffling feet. A brash woman’s voice rang out louder than the rest.

“Have you forgotten your job Welby?” she shouted. “Unannounced callers use the tradesman’s entrance. I’ll deal with you later.”

A gaggle, of what Eddie assumed were the whole family, came bustling into the room proceeded by the lady of the house. The woman eyed him up and down discourteously.

“What’s your name and business with this family?” she demanded, then turned to her butler. “Welby, remain where you are.” There was a gasp of collective horror when they heard the strangers opening words.

“My name is Egidio Francini, some call me Eddie. I am an Italian prisoner of war and was captured in the African desert campaign. I found and befriended your brother Charlie Phillips on the battlefield during his last moments, and saw to it that his belongings were handed to the British military.

By now, Eddie had everyone’s attention.

“My business here concerns Charlie’s wife Margaret. I have something for her and therefore need her address.”

It had not escaped Eddie’s notice earlier when a member of the family at the back of the room, had slipped quietly away. He was therefore not surprised when the silence beyond the stone-mullioned windows was suddenly rent by an ear splitting cacophony. There was a roar of engines and clattering lorry tailgates, as they crashed down to release hoards of noisy armed soldiers. An armoured Daimler scout car screeched to a halt beneath the front door portico, and an officer leapt out with a revolver in his hand.

“Stick your bloody hands up prisoner,” were the loud heralding words as he crashed into the room. “Good work Miss Phillips,” he remarked, “very brave of you.”

“Only doing my duty Captain,” she replied. “I want you to thoroughly search this prisoner before he leaves the room; he has something that does not belong to him. We will repair to another room whilst you do so.”

The officer motioned to a junior officer for Eddie to be searched. That ended in disaster, as Henry who was still residing in Eddie’s special pocket, took exception to the unfriendly fingers grasping about and bit them hard. A scream of pain followed as Henry leapt out and scampered for the open front door.

Daphne Phillips was furious to hear that nothing had been found on the prisoner, and even more so by his words as he was being led away.

“What you want is in my head where you can never get it, and there it will stay until I meet Charlie’s wife Margaret, face to face.”

In the meantime, Henry went post-haste through the open parkland towards the river, and followed it for a while in the summerhouse direction, but he was far from happy; this was the territory of the voracious fox and stoat.

He was suddenly startled away from that mode of thought by some crackling and crunching in some nearby trees. It was the part-time handyman he had sometimes seen from their summerhouse on Willow Farm; he was wheeling his bicycle furtively away from the riverside, where he had obviously been poaching trout. Henry stayed close behind until he reached the road. As the man mounted his bike, something small landed amongst the fish in the open bag on the rear luggage pannier. Eventually and feeling very grateful, Henry later disembarked from his transportation as it cycled past the Willow Farm front entrance.

It was probably the strong aroma of fish and the occasional snore in the summerhouse, which later enabled hungry Skungee to track down the fat sleeping form of Henry behind the settee, who in his sleeping state, dreamed that he had heard Skungee’s gruff voice say: “Fat, greedy sod. He didn’t bring any fish back for us.”

It was late afternoon before Henry emerged into the waking world, and met the grumpy stares of all those who could still smell fish but didn’t get any. But he wasn’t lost for finding a way around the situation. Pulling a photograph out from under the settee cushion, he waved it around to get everyone’s attention.

“Brilliant lot, those German prisoners at the camp,” he uttered as they all rushed over to see the picture.

“What’s this all about Henry?” enquired Sylvester.

“See these children’s toys in the photograph? The prisoners make them out of wood, and the detail is burnt on with red hot fire pokers. Most of the local “ankle biters” – children to you – are playing with them. One of the prisoners took this photograph, so I borrowed it. I’ll tell you how they work.”

They gathered around as Henry explained.

“That table-tennis bat thing in the girl’s hand has a circle of chickens on the top; each one is then connected by thin string passing through a hole in the centre of the bat, and down to a hanging weight. When the bat is moved in a circular motion, the chickens peck in turn.”

“Love it, Wow, what a smart toy,” remarked Peri.

“Here endeth another lesson,” muttered Skungee with a yawn.

“I haven’t finished yet!” shouted Henry. “That horrible creature on the wheeled things that the boy is pulling along, keeps jumping forwards to grab its little victim, who in turn, jumps out of the way. It goes on

Comments (0)