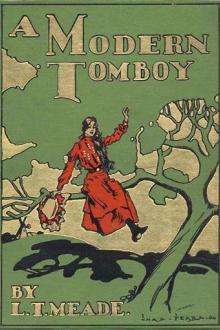

A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls by L. T. Meade (mini ebook reader TXT) 📗

- Author: L. T. Meade

Book online «A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls by L. T. Meade (mini ebook reader TXT) 📗». Author L. T. Meade

"Punish me?" said Irene, opening her eyes.

"Yes, punish you."

"Well, no. I don't think anybody would try to do it a second time."

"I don't wish to punish you, my dear child." The Professor rose and took one of Irene's little hands. "I want to help you, dear—to help you with all my might and main. I know you are different from other girls."

"Yes," said Irene, speaking in her old wild strain; "I am a changeling. That's what I am."

"Nevertheless, dear—we won't discuss that—you have a soul within you which can be touched, influenced. All I ask of you is to obey certain rules. One of them is that you do not say unkind things about your fellow-pupils. Now, you spoke very unkindly to my daughter at supper to-night."

"I don't like her," said Irene bluntly.

"But that doesn't alter the fact that she is my daughter and one of your school-fellows."

"Well, I can't like her if I can't. You don't want me to be dishonest and tell lies, do you?"

"No, but I want you to be courteous; and ill-feelings are always wrong, and can be mastered if we apply ourselves in the right spirit. I must, therefore, tell you, Irene, that the next time I hear you speak, or it is reported to me that you speak, unkindly of any of your school-fellows, and if you perform any naughty, cowardly, childish tricks, you will have to come to me, and—I don't quite know what I shall be obliged to do, but I shall have a talk with you, my dear. Now, that is enough for the present."

"Thank you," said Irene, turning very red, and immediately leaving the room.

The Professor sighed when she had gone.

"How are we ever to manage her?" he said to himself.

In truth, he had not the least idea. Irene was not the sort of girl who could be easily softened, even by a nature as gentle and kind and patient as his. She required firm measures. Nevertheless, he had made a deeper impression than he had any idea of; and when the little girl went up to her room presently, and saw that Agnes was in bed, but wide awake and waiting ready to fling her arms tightly round her companion's neck, some of the sore feeling left her heart.

"Oh, Aggie, I have you! and you will never, never love that other horrid Agnes, or that dreadful Phyllis, or that hateful Lucy, or any of the girls in the school as you love me."

"Oh, indeed, I never could, Irene—I never could!" said little Agnes. "But you don't mind Em putting me to bed, do you, for it makes her so happy? Her hands were quite trembling with joy, and she said she had not been so happy for a long time."

"Well, she is your sister, and she's a good old sort. But, Agnes, how are we to live in this school? Tell me, can you endure it?"

"I was at another school, and this one seems perfectly beautiful," said little Agnes. "I think all the girls are quite nice."

"You had better not begin to praise them overmuch, or I shall be jealous."

"What is being jealous?" said the little girl.

"Why, just furious because somebody cares for you, or even pretends to care for you. I don't want anybody to love you but myself."

"I don't think I should quite like that," said little Agnes. "Though I have promised to love you best, I should like others to be kind to me."

"There you are, with your sweet little eyes full of tears, and I have caused them! But I'm dead-tired myself. Anyhow, it will only last for twelve weeks—truly an eternity, but an eternity which has an end. Shall we sleep in one bed to-night, Agnes? I won't be a moment undressing. Will you come and cuddle close to me, and let me put my arms round you and feel that you are my own little darling?"

"Yes, indeed, I should love it!" said little Agnes.

CHAPTER XXIV. GUNPOWDER IN THE ENEMY'S CAMP.Miss Archer was a most splendid director of a school. She was the sort of woman who could read girls' characters at a glance; and as her object was to spare Mrs. Merriman all trouble, and as she was now further helped by Miss Frost, a most excellent teacher herself, and Mademoiselle Omont took the French department, there was very little trouble in arranging the lessons of the different girls.

Irene, on the morning after her arrival, awoke in a bad temper, notwithstanding the fact that sweet little gentle Agnes was lying close to her, with her pretty head of fair hair pressed against the elder girl's shoulder. But when she went downstairs, and took her place in the class, and found that, after all, she was not such an ignoramus as her companions evidently expected to find her, her spirits rose, and for the first time in her existence a sense of ambition awoke within her. It would be something to conquer Lucy Merriman—the proud, the disdainful, the unpleasant Lucy. After what Professor Merriman had said, Irene made up her mind to say nothing more in public against Lucy; but her real feelings of dislike toward her became worse and worse.

Now, Lucy's feelings towards Irene, which were those of contempt and utter indifference until they met, were now active. She was amazed to find within herself a power of disliking certain of her fellow-creatures which she never thought she could have possessed. She was not a girl to make violent friendships, but she did not know that she could dislike so heartily. She hated Rosamund with a goodly hatred, but now that hatred was extended to Irene. Why should Irene be so pretty and yet so naughty, so lovable and yet so detestable? For very soon the peculiar little girl began to exercise a certain power over more than one other girl in the school; and except that she kept herself a good deal apart, and absorbed little Agnes Frost altogether, for the first week she certainly did nothing that any one could complain of. Then she was not only remarkable for her beauty, which must arrest the attention of everybody, but she was also undeniably clever. Laura Everett was greatly taken with her, so was Annie Millar, so was Phyllis Flower, and so was Agnes Sparkes. Rosamund assumed the position of a calm and careful guardian angel over both Irene and little Agnes. She had a talk with both Mrs. Merriman and the Professor, and also with Miss Frost, on the day after their arrival.

"I will promise to be all that you want me to be if you will allow me to have a certain power over Irene and over little Agnes Frost, a power which will be felt rather than seen. I want little Agnes to sit next to Irene at meals; and I want this not for Agnes' sake—for she is such a dear little girl that she would make friends wherever she was placed—but for Irene's sake, for I don't want her to become jealous. At present she has a hard task in conquering herself, and my earnest desire is to help her all I can."

"I know that, dear," said Professor Merriman; and he looked with kind eyes at the fine, brave girl who stood upright before him.

Mrs. Merriman and Miss Frost also agreed to Rosamund's suggestion, and in consequence there was a certain amount of peace in the school. This peace might have gone on, and things might have proved eminently satisfactory, had it not been for Lucy herself. But Lucy could now scarcely contain her feelings. Rosamund exceeded her in power of acquiring knowledge; she excelled her in grace and beauty. And now there was Rosamund's friend, a much younger girl, who in some ways was already Lucy's superior; for Irene had a talent for music that amounted to genius, whereas Lucy's music was inclined to be merely formal, although very correct. There were other things, too, that little Irene could pick up even at a word or a glance. Agnes did not much matter; her talents were quite ordinary. She was just a loving and lovable little child, that was all; but when Lucy sometimes met a glance of triumph in Rosamund's dark eyes, and saw the light dancing in Irene's, she began to turn round and plan for herself how she could work out a very pretty little scheme of revenge.

Now, there seemed no more secure way of doing this than by detaching little Agnes from Irene; for, however naughty Irene might be, however careless at her tasks, one glance at her little companion had always the effect of soothing her. Suppose Lucy were to make little Agnes her friend? That certainly would seem a very simple motive; for Lucy, in reality, was not interested in small children. She acknowledged that Agnes had more charm than most of her companions, and, in short, she was worth winning.

"The first thing I must do is to detach her from Irene. She does not know anything about Irene at present, but I can soon open her eyes," thought Lucy to herself.

The school began, as almost all schools do, toward the middle of September, and it was on a certain afternoon in a very sunny and warm October that Lucy invited little Agnes Frost to take a walk with her. She did this feeling sure that the child would come willingly, for both Irene and Rosamund were spending the half-holiday at The Follies. Miss Frost was busily engaged, and beginning to enjoy her life, and little Agnes was standing in her wistful way by one of the doors of the schoolroom when Lucy came by.

"Why, Agnes," said Lucy, "have you no one to play with?"

"Oh, yes, I have every one," said Agnes, raising her eyes, which appealed to all hearts; "only my darling Irene is away, and I miss her."

"Well, you can't expect her to be always with you—can you?"

"Of course not. It is very selfish of me; but I miss her all the same."

"Now, suppose," said Lucy suddenly—"suppose you take me as your friend this afternoon. What shall we do? I am a good bit older than you, but I am fond of little girls."

Agnes looked at Lucy. In truth, she had never disliked any one; but Lucy Merriman was as little to her taste as any girl could be.

"There's Agnes Sparkes. Perhaps she wouldn't mind playing with me," said she after a pause.

"As you please, child. If you prefer Agnes you can go and search for her."

"No, no, I don't," said Agnes, who wouldn't hurt a fly if she could help it. "I will go for a walk with you, Miss Merriman."

"Lucy, if you please," said Lucy. "We are both school-fellows, are we not?"

"Only I feel so very small, and so very nothing at all beside you," replied Agnes.

"But you are a good deal beside me. It is true you are small; but how old are you?"

"I was eleven my last birthday. I am two years younger than dear Irene; but Irene says that I am ten years older than she is in some ways."

"Twenty—thirty—forty, I should say," remarked Lucy, with a laugh. "Well, come along; let's have a good time. What shall we do?"

"Whatever you like—Lucy," said the little girl, making a pause before she ventured on the Christian name.

"That's right. I am glad you called me Lucy. We all like you, little Agnes; and it isn't in every school where the sister of one of the governesses would be tolerated as you are tolerated here."

"I don't quite understand what you mean by that."

"Well, your sister is one of the governesses."

"Yes, I know."

"And yet we are all very fond of you."

"It is very kind of you; but they were all fond of me at Mrs. England's school; and when I was at that sort of school at Mrs. Henderson's, where there were boys as well as girls, the girls used to quarrel with the boys as to who was to play with me. People have always been kind to me. I don't exactly know why."

"But I do, I think," said Lucy; "because you are taking, and can make people love you. It is a great gift. Now, give me your hand. We'll walk along by the riverside. It's so pretty there, is it not?"

"Yes, lovely," said little Agnes.

Lucy walked fast. Presently they sat down on a low mossy bank, and Lucy spread out her skirt so that Agnes might sit on it, so as to avoid any chance of taking a chill.

"You see how careful I am of you," said the elder girl.

"All the girls are careful of me like that," said little Agnes. "I don't exactly know why. Am I so very,

Comments (0)