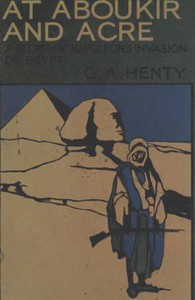

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt by G. A. Henty (free novels to read txt) 📗

- Author: G. A. Henty

Book online «At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt by G. A. Henty (free novels to read txt) 📗». Author G. A. Henty

Here too were a quantity of European manufactures, showing that it was not only native craft that had suffered from their depredations. There were numbers of barrels of Greek wine, puncheons of rum, cases of bottled wines of different kinds evidently taken from English ships, great quantities of Smyrna figs, and of currants, Egyptian dates, and sacks of flour.

"This will bring us in a nice lot of prize-money, Blagrove," Wilkinson said, after they had roughly examined the contents of the great subterranean storehouses. Presently a still larger find was made. There was, close to the houses, what appeared to be a well. One of the sailors let down a bucket, and hauling it up found, to his surprise, that it was salt water. The well was deep, but certainly not deep enough to reach down to the sea level, and he carried the bucket to Wilkinson and pointed out where he had got the water from.

"There is something curious about this," the latter said. "Lower me down in the bucket, lads." As he descended he saw that the well was an ancient one, and probably at one time had been carried very much lower than at present. In some places the masonry had fallen in. At one of these points there was an opening cut into the rock. He called to those above to hoist him up again, and procuring a lamp at one of the houses, he and Edgar descended together. Entering the passage they found that it widened into a great[Pg 268] chamber some forty feet square and thirty high, which was literally crammed with goods.

"I should never have given the fellows credit for having taken the trouble to cut out such a place as this," Wilkinson said.

"I have no doubt that it is ancient work," Edgar remarked. "I should say that at some time, perhaps when the Genoese were masters here, a castle may have stood above, and this was cut either as a storehouse or as a place of confinement for prisoners, or one where the garrison might hide themselves, with provisions enough to last for a long time, in case the place was captured. The pirates may have discovered it in going down to see if the well could be cleared out, and saw that it would make a splendid place of concealment."

"But how about the salt water, Edgar?"

"I should say that they cemented the bottom or rammed it with clay to make it water-tight, and that as fresh water was scarce they brought up sea water, so that anyone who happened to look down would see that there was water in it. If, as was probable, it would be the Turks who captured the place, they would, when they found that it was salt, not trouble their heads further about the matter. Possibly even these pirates may know nothing of the existence of this store, which may have lain here since the last time the Turks broke up this nest of pirates, and who, you may be sure, left none of them alive to tell the tale. Well, this is a find."

A thorough search was now made of the island, but it was found that the whole of the pirates had made their escape in boats. These had rowed away from the seaward face of the island, so that they were unseen by those on board the brig. Before taking any step to carry away the goods, the[Pg 269] other islets were all visited and found to be deserted. Five or six more magazines of spoil were discovered. These were emptied of their most valuable contents, and the houses all burned to the ground. This operation took two days, and it required six more to transfer the contents of the cellars and great store cavern to the brig. Boats had come off on the first day of their arrival from various villages in the bay, conveying one or more of the principal inhabitants, who assured Wilkinson that they had no connection whatever with the pirates, and that they were extremely glad that their nest had been destroyed.

Wilkinson had little doubt that, although they might not have been concerned in the deeds committed by these men, they must have been in constant communication with them, and have supplied them with fruit and fresh meat and vegetables. However, he told them that he should report their assurances to the Turkish authorities, who would, when they had a ship of war available, doubtless send down and inquire into the whole circumstances, an intimation which caused them considerable alarm, as they had no doubt that, if no worse befell them, they would be made to pay heavy fines.

"The only way that you have to show your earnestness in the matter," Wilkinson said, "is to organize yourselves. You have no doubt plenty of boats, and the first time that a pirate comes in here row out from all your villages, attack and burn it, and don't leave a man alive to tell the tale. In that way the pirates will very soon learn that they'd better choose some other spot for their rendezvous, and the authorities will be well content with your conduct."

The amount of spoil taken was so great that the Tigress, when she set sail again, was nearly a foot deeper in the water than when she entered the bay. The prisoners had been the subject of much discussion. It was agreed that[Pg 270] they were probably no worse than their comrades who had escaped, and they did not like the thought of handing them over to be executed. They were, therefore, on the third day after the arrival of the brig, brought up on deck. Three dozen lashes were administered to each, then they were given one of the boats in which they had attacked the ship, and told to go.

CHAPTER XV. CRUISING.Before sailing, the yellow band was painted out, for the pirates who escaped would probably carry the news of what had happened over the whole archipelago. Ten men were put on board each of the prizes, and the Tigress sailed up through the islands and escorted them to Smyrna, where the pasha, after hearing an account of their capture, at once gave permission for them to be sold as prizes, and as the news of the retreat of the French had given a considerable impetus to trade, they fetched good prices. As soon as this was arranged, the Tigress sailed away again. For some months they cruised among the islands, putting into every little bay and inlet, boarding every craft found there, and searching her thoroughly to see if there was any property belonging to plundered vessels on board.

Once or twice she came upon two or three large craft together, and had some hard fighting before she captured or sank them; but, as a rule, the crews rowed ashore as soon as they saw the real nature of the new-comer. Some thirty craft were sent as prizes into Smyrna or Rhodes, and there sold, as many more were sunk or burned. They had, in no case, found spoil at all equal to that which had been cap[Pg 271]tured at Astropalaia, but the total was nevertheless considerable. Once or twice they were attacked by boats when anchored in quiet bays, but as a vigilant watch was always kept they beat off their assailants with heavy loss. The rig of the brig was frequently altered. Sometimes she was turned into a schooner with yards on her foremast, sometimes into a fore-and-aft craft; and as the time went on and captures became fewer and fewer, it was evident that she had established a thorough scare throughout the archipelago, and that for the time the pirates had taken to peaceful avocations, and were indeed completely crippled by the loss of so large a number of their craft.

The Tigress had but one awkward incident during the voyage. The day was bright and clear. The two Turks had been, as was their custom, squatting together on the deck, smoking their pipes. Wilkinson and Edgar were pacing together up and down, when the latter said:

"Look at these two native craft; they have both let their lateen sails run down. I am sure I don't know why; there is not a cloud in the sky, except that little white one over there."

They were passing the Turks at the moment, and Edgar said to one of them:

"The two craft over there have just let their sails run down. What can that mean?"

The Turk leapt to his feet with a quickness very unusual to him.

"It is a white squall!" he shouted. "Down with every stitch of canvas, sir. Quick, for your lives! the squall will be upon us in five minutes."

It was Wilkinson's first experience of the terribly sudden squall of the Levant, but he had heard of them and knew their danger, and he shouted at the top of his voice:[Pg 272]

"All hands take in sail! Quick, lads, for your lives!"

The boatswain's whistle rang loudly in the air, and he repeated the order at the top of his voice. The men on deck, who had been engaged on various small jobs since they came up from dinner, looked astounded at the order, but without hesitation ran up the ratlines at the top of their speed, while the watch below looked equally surprised as they glanced upwards and around at the deep blue of the sky.

"Quick, quick!" the Turk exclaimed. "Let go all sheets and halliards!"

Wilkinson shouted, "Do the sails up anyhow, men."

Although the sky was unchanged they could see the light cloud Edgar had noticed advancing towards them at an extraordinary rate of speed, while a white line on the sea kept pace with it.

"Hard up with the helm—hard up!" Wilkinson shouted. "Hold on a moment with those head sails; that will do, that will do. Let go the halliards; down staysails and jib."

The sailors, now conscious of the coming danger, worked desperately. The light upper sails were secured, the courses had been clewed up, but the topsails were still but half-lashed when Wilkinson shouted again:

"Down for your lives! Down on the weather side; slip down by the back-stays. You men to leeward, hold on—all hold on," he shouted a few seconds later.

There was a dull roaring sound, rising to a shriek as the squall struck the vessel.

Most of the men had gained the deck in safety, but many of those coming down by the ratlines were still some distance from the deck. It was well for them that they were on the weather side; had they been to leeward they would have been torn from their grasp, whereas they were now[Pg 273] pinned to the rigging. Two sounds like the explosion of cannon were heard. The main and foretopsails both blew out of their gaskets, bellied for an instant, and then burst from the bolt-ropes and flew away, and were speedily lost to sight. So great was the pressure that the brig was driven bodily down until the water was almost level with the rail at the bow, and it looked for a moment as if she would go down by the head.

One of the jibs was run up, but only to be blown away before it was sheeted home. Another was tried, the sheet being kept very slack. This held, her head lifted, and in a minute the Tigress was flying along dead before the wind. The storm-jib was brought up, hooked on, and hoisted. This, being of very heavy canvas, could be trusted, and as soon as it was set the other was hauled down.

"Thank God, that is over!" Wilkinson said, "and we have not lost a hand."

By this time all the men had gained the deck.

"How long will this last?" Edgar shouted in one of the Turks' ears.

"Perhaps one hour; perhaps four."

"Let us have a look at the chart," Wilkinson said. "When we last looked there was a group of rocks ten miles ahead, and at the rate we are going the Tigress will be smashed into matchwood if she keeps on this course for long."

Edgar nodded.

"We must get trysails on the main and foremast," Wilkinson went on, "and manage to lay her course a couple of points to the west. I wish we had those upper spars down on deck, but it is of no use talking of

Comments (0)