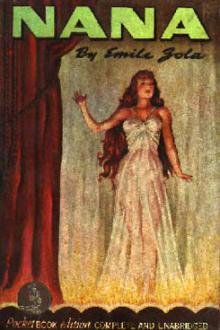

Nana - Émile Zola (good books to read for young adults txt) 📗

- Author: Émile Zola

- Performer: -

Book online «Nana - Émile Zola (good books to read for young adults txt) 📗». Author Émile Zola

married your wife. You were still like that, eh? Is it true, eh?”

Her eyes pressed for an answer, and she raised her hands to his

shoulders and began shaking him in order to extract the desired

confession.

“Without doubt,” he at last made answer gravely.

Thereupon she again sank down at his feet. She was shaking with

uproarious laughter, and she stuttered and dealt him little slaps.

“No, it’s too funny! There’s no one like you; you’re a marvel.

But, my poor pet, you must just have been stupid! When a man

doesn’t know—oh, it is so comical! Good heavens, I should have

liked to have seen you! And it came off well, did it? Now tell me

something about it! Oh, do, do tell me!”

She overwhelmed him with questions, forgetting nothing and requiring

the veriest details. And she laughed such sudden merry peals which

doubled her up with mirth, and her chemise slipped and got turned

down to such an extent, and her skin looked so golden in the light

of the big fire, that little by little the count described to her

his bridal night. He no longer felt at all awkward. He himself

began to be amused at last as he spoke. Only he kept choosing his

phrases, for he still had a certain sense of modesty. The young

woman, now thoroughly interested, asked him about the countess.

According to his account, she had a marvelous figure but was a

regular iceberg for all that.

“Oh, get along with you!” he muttered indolently. “You have no

cause to be jealous.”

Nana had ceased laughing, and she now resumed her former position

and, with her back to the fire, brought her knees up under her chin

with her clasped hands. Then in a serious tone she declared:

“It doesn’t pay, dear boy, to look like a ninny with one’s wife the

first night.”

“Why?” queried the astonished count.

“Because,” she replied slowly, assuming a doctorial expression.

And with that she looked as if she were delivering a lecture and

shook her head at him. In the end, however, she condescended to

explain herself more lucidly.

“Well, look here! I know how it all happens. Yes, dearie, women

don’t like a man to be foolish. They don’t say anything because

there’s such a thing as modesty, you know, but you may be sure they

think about it for a jolly long time to come. And sooner or later,

when a man’s been an ignoramus, they go and make other arrangements.

That’s it, my pet.”

He did not seem to understand. Whereupon she grew more definite

still. She became maternal and taught him his lesson out of sheer

goodness of heart, as a friend might do. Since she had discovered

him to be a cuckold the information had weighed on her spirits; she

was madly anxious to discuss his position with him.

“Good heavens! I’m talking of things that don’t concern me. I’ve

said what I have because everybody ought to be happy. We’re having

a chat, eh? Well then, you’re to answer me as straight as you can.”

But she stopped to change her position, for she was burning herself.

“It’s jolly hot, eh? My back’s roasted. Wait a second. I’ll cook

my tummy a bit. That’s what’s good for the aches!”

And when she had turned round with her breast to the fire and her

feet tucked under her:

“Let me see,” she said; “you don’t sleep with your wife any longer?”

“No, I swear to you I don’t,” said Muffat, dreading a scene.

“And you believe she’s really a stick?”

He bowed his head in the affirmative.

“And that’s why you love me? Answer me! I shan’t be angry.”

He repeated the same movement.

“Very well then,” she concluded. “I suspected as much! Oh, the

poor pet. Do you know my aunt Lerat? When she comes get her to

tell you the story about the fruiterer who lives opposite her. Just

fancy that man—Damn it, how hot this fire is! I must turn round.

I’m going to roast my left side now.” And as she presented her side

to the blaze a droll idea struck her, and like a good-tempered

thing, she made fun of herself for she was dellghted to see that she

was looking so plump and pink in the light of the coal fire.

“I look like a goose, eh? Yes, that’s it! I’m a goose on the spit,

and I’m turning, turning and cooking in my own juice, eh?”

And she was once more indulging in a merry fit of laughter when a

sound of voices and slamming doors became audible. Muffat was

surprised, and he questioned her with a look. She grew serious, and

an anxious expression came over her face. It must be Zoe’s cat, a

cursed beast that broke everything. It was half-past twelve

o’clock. How long was she going to bother herself in her cuckold’s

behalf? Now that the other man had come she ought to get him out of

the way, and that quickly.

“What were you saying?” asked the count complaisantly, for he was

charmed to see her so kind to him.

But in her desire to be rid of him she suddenly changed her mood,

became brutal and did not take care what she was saying.

“Oh yes! The fruiterer and his wife. Well, my dear fellow, they

never once touched one another! Not the least bit! She was very

keen on it, you understand, but he, the ninny, didn’t know it. He

was so green that he thought her a stick, and so he went elsewhere

and took up with streetwalkers, who treated him to all sorts of

nastiness, while she, on her part, made up for it beautifully with

fellows who were a lot slyer than her greenhorn of a husband. And

things always turn out that way through people not understanding one

another. I know it, I do!”

Muffat was growing pale. At last he was beginning to understand her

allusions, and he wanted to make her keep silence. But she was in

full swing.

“No, hold your tongue, will you? If you weren’t brutes you would be

as nice with your wives as you are with us, and if your wives

weren’t geese they would take as much pains to keep you as we do to

get you. That’s the way to behave. Yes, my duck, you can put that

in your pipe and smoke it.”

“Do not talk of honest women,” he said in a hard voice. “You do not

know them.”

At that Nana rose to her knees.

“I don’t know them! Why, they aren’t even clean, your honest women

aren’t! They aren’t even clean! I defy you to find me one who

would dare show herself as I am doing. Oh, you make me laugh with

your honest women. Don’t drive me to it; don’t oblige me to tell

you things I may regret afterward.”

The count, by way of answer, mumbled something insulting. Nana

became quite pale in her turn. For some seconds she looked at him

without speaking. Then in her decisive way:

“What would you do if your wife were deceiving you?”

He made a threatening gesture.

“Well, and if I were to?”

“Oh, you,” he muttered with a shrug of his shoulders.

Nana was certainly not spiteful. Since the beginning of the

conversation she had been strongly tempted to throw his cuckold’s

reputation in his teeth, but she had resisted. She would have liked

to confess him quietly on the subject, but he had begun to

exasperate her at last. The matter ought to stop now.

“Well, then, my dearie,” she continued, “I don’t know what you’re

getting at with me. For two hours past you’ve been worrying my life

out. Now do just go and find your wife, for she’s at it with

Fauchery. Yes, it’s quite correct; they’re in the Rue Taitbout, at

the corner of the Rue de Provence. You see, I’m giving you the

address.”

Then triumphantly, as she saw Muffat stagger to his feet like an ox

under the hammer:

“If honest women must meddle in our affairs and take our sweethearts

from us—Oh, you bet they’re a nice lot, those honest women!”

But she was unable to proceed. With a terrible push he had cast her

full length on the floor and, lifting his heel, he seemed on the

point of crushing in her head in order to silence her. For the

twinkling of an eye she felt sickening dread. Blinded with rage, he

had begun beating about the room like a maniac. Then his choking

silence and the struggle with which he was shaken melted her to

tears. She felt a mortal regret and, rolling herself up in front of

the fire so as to roast her right side, she undertook the task of

comforting him.

“I take my oath, darling, I thought you knew it all. Otherwise I

shouldn’t have spoken; you may be sure. But perhaps it isn’t true.

I don’t say anything for certain. I’ve been told it, and people are

talking about it, but what does that prove? Oh, get along! You’re

very silly to grow riled about it. If I were a man I shouldn’t care

a rush for the women! All the women are alike, you see, high or

low; they’re all rowdy and the rest of it.”

In a fit of self-abnegation she was severe on womankind, for she

wished thus to lessen the cruelty of her blow. But he did not

listen to her or hear what she said. With fumbling movements he had

put on his boots and his overcoat. For a moment longer he raved

round, and then in a final outburst, finding himself near the door,

he rushed from the room. Nana was very much annoyed.

“Well, well! A prosperous trip to you!” she continued aloud, though

she was now alone. “He’s polite, too, that fellow is, when he’s

spoken to! And I had to defend myself at that! Well, I was the

first to get back my temper and I made plenty of excuses, I’m

thinking! Besides, he had been getting on my nerves!”

Nevertheless, she was not happy and sat scratching her legs with

both hands. Then she took high ground:

“Tut, tut, it isn’t my fault if he is a cuckold!”

And toasted on every side and as hot as a roast bird, she went and

buried herself under the bedclothes after ringing for Zoe to usher

in the other man, who was waiting in the kitchen.

Once outside, Muffat began walking at a furious pace. A fresh

shower had just fallen, and he kept slipping on the greasy pavement.

When he looked mechanically up into the sky he saw ragged, soot-colored clouds scudding in front of the moon. At this hour of the

night passers-by were becoming few and far between in the Boulevard

Haussmann. He skirted the enclosures round the opera house in his

search for darkness, and as he went along he kept mumbling

inconsequent phrases. That girl had been lying. She had invented

her story out of sheer stupidity and cruelty. He ought to have

crushed her head when he had it under his heel. After all was said

and done, the business was too shameful. Never would he see her;

never would he touch her again, or if he did he would be miserably

weak. And with that he breathed hard, as though he were free once

more. Oh, that naked, cruel monster, roasting away like

Comments (0)