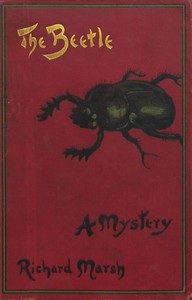

The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (books for 10th graders TXT) 📗

- Author: Richard Marsh

Book online «The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (books for 10th graders TXT) 📗». Author Richard Marsh

‘Every moment I expects to hear a noise and see a row begin, but, so far as I could make out, all was quiet and there wasn’t nothing of the kind. So I says to myself, “There’s more in this than meets the eye, and them three parties must have right upon their side, or they wouldn’t be doing what they are doing in the way they are, there’d be a shindy.”

‘Presently, in about five minutes, the front door opens, and a young man—not the one what’s your friend, but the other—comes sailing out, and through the gate, and down the road, as stiff and upright as a grenadier,—I never see anyone walk more upright, and few as fast. At his heels comes the young man what is your friend, and it seems to me that he couldn’t make out what this other was a-doing of. I says to myself, “There’s been a quarrel between them two, and him as has gone has hooked it.” This young man what is your friend he stood at the gate, all of a fidget, staring after the other with all his eyes, as if he couldn’t think what to make of him, and the young woman, she stood on the doorstep, staring after him too.

‘As the young man what had hooked it turned the corner, and was out of sight, all at once your friend he seemed to make up his mind, and he started off running as hard as he could pelt,—and the young woman was left alone. I expected, every minute, to see him come back with the other young man, and the young woman, by the way she hung about the gate, she seemed to expect it too. But no, nothing of the kind. So when, as I expect, she’d had enough of waiting, she went into the house again, and I see her pass the front room window. After a while, back she comes to the gate, and stands looking and looking, but nothing was to be seen of either of them young men. When she’d been at the gate, I daresay five minutes, back she goes into the house,—and I never saw nothing of her again.’

‘You never saw anything of her again?—Are you sure she went back into the house?’

‘As sure as I am that I see you.’

‘I suppose that you didn’t keep a constant watch upon the premises?’

‘But that’s just what I did do. I felt something queer was going on, and I made up my mind to see it through. And when I make up my mind to a thing like that I’m not easy to turn aside. I never moved off the chair at my bedroom window, and I never took my eyes off the house, not till you come knocking at my front door.’

‘But, since the young lady is certainly not in the house at present, she must have eluded your observation, and, in some manner, have left it without your seeing her.’

‘I don’t believe she did, I don’t see how she could have done,—there’s something queer about that house, since that Arab party’s been inside it. But though I didn’t see her, I did see someone else.’

‘Who was that?’

‘A young man.’

‘A young man?’

‘Yes, a young man, and that’s what puzzled me, and what’s been puzzling me ever since, for see him go in I never did do.’

‘Can you describe him?’

‘Not as to the face, for he wore a dirty cloth cap pulled down right over it, and he walked so quickly that I never had a proper look. But I should know him anywhere if I saw him, if only because of his clothes and his walk.’

‘What was there peculiar about his clothes and his walk?’

‘Why, his clothes were that old, and torn, and dirty, that a ragman wouldn’t have given a thank you for them,—and as for fit,—there wasn’t none, they hung upon him like a scarecrow—he was a regular figure of fun; I should think the boys would call after him if they saw him in the street. As for his walk, he walked off just like the first young man had done, he strutted along with his shoulders back, and his head in the air, and that stiff and straight that my kitchen poker would have looked crooked beside of him.’

‘Did nothing happen to attract your attention between the young lady’s going back into the house and the coming out of this young man?’

Miss Coleman cogitated.

‘Now you mention it there did,—though I should have forgotten all about it if you hadn’t asked me,—that comes of your not letting me tell the tale in my own way. About twenty minutes after the young woman had gone in someone put up the blind in the front room, which that young man had dragged right down, I couldn’t see who it was for the blind was between us, and it was about ten minutes after that that young man came marching out.’

‘And then what followed?’

‘Why, in about another ten minutes that Arab party himself comes scooting through the door.’

‘The Arab party?’

‘Yes, the Arab party! The sight of him took me clean aback. Where he’d been, and what he’d been doing with himself while them there people played hi-spy-hi about his premises I’d have given a shilling out of my pocket to have known, but there he was, as large as life, and carrying a bundle.’

‘A bundle?’

‘A bundle, on his head, like a muffin-man carries his tray. It was a great thing, you never would have thought he could have carried it, and it was easy to see that it was as much as he could manage; it bent him nearly double, and he went crawling along like a snail,—it took him quite a time to get to the end of the road.’

Mr Lessingham leaped up from his seat, crying,

‘Marjorie was in that bundle!’

‘I doubt it,’ I said.

He moved about the room distractedly, wringing his hands.

‘She was! she must have been! God help us all!’

‘I repeat that I doubt it. If you will be advised by me you will wait awhile before you arrive at any such conclusion.’

All at once there was a tapping at the window pane. Atherton was staring at us from without.

He shouted through the glass,

‘Come out of that, you fossils!—I’ve news for you!’

CHAPTER XLI.THE CONSTABLE,—HIS CLUE,—AND THE CAB

Miss Coleman, getting up in a fluster, went hurrying to the door.

‘I won’t have that young man in my house. I won’t have him! Don’t let him dare to put his nose across my doorstep.’

I endeavoured to appease her perturbation.

‘I promise you that he shall not come in, Miss Coleman. My friend here, and I, will go and speak to him outside.’

She held the front door open just wide enough to enable Lessingham and me to slip through, then she shut it after us with a bang. She evidently had a strong objection to any intrusion on Sydney’s part.

Standing just without the gate he saluted us with a characteristic vigour which was scarcely flattering to our late hostess. Behind him was a constable.

‘I hope you two have been mewed in with that old pussy long enough. While you’ve been tittle-tattling I’ve been doing,—listen to what this bobby’s got to say.’

The constable, his thumbs thrust inside his belt, wore an indulgent smile upon his countenance. He seemed to find Sydney amusing. He spoke in a deep bass voice,—as if it issued from his boots.

‘I don’t know that I’ve got anything to say.’

It was plain that Sydney thought otherwise.

‘You wait till I’ve given this pretty pair of gossips a lead, officer, then I’ll trot you out.’ He turned to us.

‘After I’d poked my nose into every dashed hole in that infernal den, and been rewarded with nothing but a pain in the back for my trouble, I stood cooling my heels on the doorstep, wondering if I should fight the cabman, or get him to fight me, just to pass the time away,—for he says he can box, and he looks it,—when who should come strolling along but this magnificent example of the metropolitan constabulary.’ He waved his hand towards the policeman, whose grin grew wider. ‘I looked at him, and he looked at me, and then when we’d had enough of admiring each other’s fine features and striking proportions, he said to me, “Has he gone?” I said, “Who?—Baxter?—or Bob Brown?” He said, “No, the Arab.” I said, “What do you know about any Arab?” He said, “Well, I saw him in the Broadway about three-quarters of an hour ago, and then, seeing you here, and the house all open, I wondered if he had gone for good.” With that I almost jumped out of my skin, though you can bet your life I never showed it. I said, “How do you know it was he?” He said, “It was him right enough, there’s no doubt about that. If you’ve seen him once, you’re not likely to forget him.” “Where was he going?” “He was talking to a cabman,—four-wheeler. He’d got a great bundle on his head,—wanted to take it inside with him. Cabman didn’t seem to see it.” That was enough for me,—I picked this most deserving officer up in my arms, and carried him across the road to you two fellows like a flash of lightning.’

Since the policeman was six feet three or four, and more than sufficiently broad in proportion, his scarcely seemed the kind of figure to be picked up in anybody’s arms and carried like a ‘flash of lightning,’ which,—as his smile grew more indulgent, he himself appeared to think.

Still, even allowing for Atherton’s exaggeration, the news which he had brought was sufficiently important. I questioned the constable upon my own account.

‘There is my card, officer, probably, before the day is over, a charge of a very serious character will be preferred against the person who has been residing in the house over the way. In the meantime it is of the utmost importance that a watch should be kept upon his movements. I suppose you have no sort of doubt that the person you saw in the Broadway was the one in question?’

‘Not a morsel. I know him as well as I do my own brother,—we all do upon this beat. He’s known amongst us as the Arab. I’ve had my eye on him ever since he came to the place. A queer fish he is. I always have said that he’s up to some game or other. I never came across one like him for flying about in all sorts of weather, at all hours of the night, always tearing along as if for his life. As I was telling this gentleman I saw him in the Broadway,—well, now it’s about an hour since, perhaps a little more. I was coming on duty when I saw a crowd in front of the District Railway Station,—and there was the Arab, having a sort of argument with the cabman. He had a great bundle on his head, five or six feet long, perhaps longer. He wanted to take this great bundle with him into the cab, and the cabman, he didn’t see it.’

‘You didn’t wait to see him drive off.’

‘No,—I hadn’t time. I was due at the station,—I was cutting it pretty fine as it was.’

‘You didn’t speak to him,—or to the cabman?’

‘No, it wasn’t any business of mine you understand. The whole thing just caught my eye as I was passing.’

‘And you didn’t take the cabman’s number?’

‘No, well, as far as that goes it wasn’t needful. I know the cabman, his name and all about him, his stable’s in Bradmore.’

I whipped out my note-book.

‘Give me his address.’

‘I don’t know what his Christian name is, Tom, I believe, but I’m not sure. Anyhow his surname’s Ellis and his address is Church Mews, St John’s Road, Bradmore,—I don’t know his number, but any one will tell you which is his place, if you ask for Four-Wheel Ellis,—that’s the name he’s known by among his pals because of his driving a four-wheeler.’

‘Thank you, officer. I am obliged to you.’ Two half-crowns changed hands. ‘If you will keep an eye on the house and advise me at the address which you will find on my card, of any thing which takes place there

Comments (0)