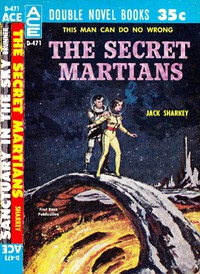

The Secret Martians by Jack Sharkey (best historical fiction books of all time TXT) 📗

- Author: Jack Sharkey

Book online «The Secret Martians by Jack Sharkey (best historical fiction books of all time TXT) 📗». Author Jack Sharkey

Snow smiled helplessly, "Ice, of course. You make it sound almost idiotically simple." Then her face fell. "But it's only a theory, isn't it! Or is it?"

I shrugged. "It seems borne out by a few things, Snow. When I entered the Phobos, I checked beneath the canvas covering on one of the takeoff racks. There was grit there, which is a little unusual on a military vessel, with their one-track-mindedness about things being spic and span. And water running through canvas, taking along the dirt that even a military white-glove inspection can't find, leaves behind a residue of grit."

"It still doesn't seem enough," she said wistfully, as if begging me to prove my theory correct for her peace of mind. I was glad to oblige.

"There's more. Water weighs in at 62.4 pounds per cubic foot. So, fifteen hundred pounds of water would occupy approximately twenty four cubic feet; the exact surplus found aboard the Phobos II, in the bulkhead tubing."

Snow looked startled, but still unconvinced. "To kidnap fifteen boys, without Anders noting even the slightest sign of a struggle or disturbance...."

I nodded. "Right. It is odd, isn't it! This bothered me, too, until I checked the contents of those storage lockers."

"Oh. I'd forgotten about that!" she exclaimed. "What did you find?"

"Roughly, without going into precise itemization, there were bottles of space sickness capsules, clean handkerchiefs, toothbrushes, packets of soap and the like."

"And the like?" Snow remarked. "What likeness is there between those things?"

I smiled happily, and told her, simply, the clinker I'd spotted at once on seeing those items: "They're all items which small boys hate with almost apocalyptic fury. But I did not find such things as jackknives, candy, chewing gum—Shall I go on?"

"You mean that whoever kidnapped the boys took along the things which the boys wanted?" she asked, her lovely voice making an unbelieving squeak on the last word.

"I mean," I said softly, "that I believe the Space Scouts left the Phobos II of their own free will."

7By evening of the following day we were in descent toward Marsport; a slow planet-circling downward spiral with a steady braking by the nose jets, lest we hit the atmosphere too fast and burn up. Even a thin atmosphere like that of Mars was no fun to enter at interplanetary speeds.

Snow, looking through the viewport beside her chair in the lounge, sighed gently and turned her lovely gaze back to my face. "I wish—" she began softly.

I laid my hand upon hers. "We've been over that, Snow. You must return to Earth. You haven't a chance of finding those boys. Hell, if you had, the Brain would have picked you. And I, with the Amnesty, can go anywhere, do anything, get results in a hurry."

"But if I came with you...." she pleaded in a tense whisper.

I shook my head, with finality. "I've told you over and over. You wreck my spotter's instinct, Snow. If you're with me, I'll never be able to locate those boys. I'll miss even obvious clues."

"You weren't so fuddleheaded yesterday when you told me how you'd reasoned out the real facts about the disappearance," she accused.

"Hell, your presence affects my thinking, not my memory! Come on, now, see it my way, will you?"

I stood up. "It looks like good-by for a while, Snow."

She faced me, solemnly. "Yes, it does. You'll be careful, won't you? And you'll let me know if—if—"

"I promise. Before I let Baxter know, even!"

We stood like that a moment, scarcely a foot apart, and I fought an impulse to take her into my arms. Then, with no warning, she flung her arms about my neck, and I had my first taste of those red velvet lips.

Then she was gone from the lounge. I glanced at the wall chronometer, and began to move toward my cabin in a hurry. Less than five minutes till set-down. I entered at a dead run.

I'd barely lashed myself to the rack when the landing thrust began. However, I'd taken two antipressure tablets, as per the instructions posted in the room, and I was comfortably unconscious even before the pressure began to grow.

When I awoke, there were two men in red and bronze uniforms standing over my rack. They didn't seem very pleased to find me there. One of them had my bag open, and was holding my collapser in his hand, and the look he was giving me wasn't the cheeriest I'd ever seen.

"What are you guys doing here?" I demanded. In speaking, I tried to gesture. That's when I became aware of the cold steel manacles on my wrists. "What the hell?"

The one with the weapon hefted it thoughtfully in his palm. "Don't you know it's a death-penalty offense to have possession of a collapser, chum?" he said.

The other one, not waiting for my answer, began undoing the straps across my body, and assisting me to my feet.

"Say, look, what do you guys mean by coming here and—"

"We were alerted," said the first man. "By an Amnesty-bearer."

I simply stared at him for an unbelieving instant. Then I said, "You're crazy! There's only one Amnesty in existence, and—"

With horrible clarity, I recalled Snow's impassioned farewell in the lounge, and the way her hands had darted about; my neck.

I brought my manacled hands up to my blouse and felt frantically for the red and bronze disc. The Amnesty was gone.

"Come along, now," said the one who'd helped me up.

"Where are we going?" I demanded.

"You're to be held incommunicado," he said, "until the Amnesty-bearer returns. Come along, now. We haven't got all day!"

"Day?" I said, and looked toward the viewport. Sure enough the glaring Martian sunlight was pouring into the cabin. "But we were landing on the night side," I said, confused.

"You did," said the one with the collapser. "Only it was arranged that you'd stay asleep for a while, till we could get here."

"Arranged how?" I choked furiously. Then I remembered the capsules I'd taken. I looked toward the instruction posted on the inside of the cabin door. Now that I was in no great hurry, I could see where someone had, with ordinary pen and ink, gone over the numeral 1, and made it into a passable 2. Someone, I thought bitterly, with shimmering cornsilk hair and red velvet lips!

"Now, just a minute, you guys, I can explain." I said.

"Stow it," said the one with the gun. "Come on, get moving."

"When Chief Baxter hears about this—" I growled.

He laughed. "You know Baxter has no authority to over-ride an Amnesty-bearer's orders!" Once again, he motioned with the collapser in the direction of the door.

"Well then, boys," I said, in as threatening a tone as I could muster, "let your fat heads chew on this for a while: the girl who has that Amnesty stole it from me! You just get hold of Baxter and verify it. Because if you don't, there are going to be two slightly-used Security Agent's uniforms for sale!"

They looked at each other, frowning. Then the one with the gun scowled. The other guy paled. "Say, Charlie, what if there is something to his story? What do you think we ought to do?"

Charlie blinked and thought hard. Then a smile crossed his face. "Nothing," he said. "We were given orders by an Amnesty-bearer, and all we have to do is carry them out to be in the clear."

"Oh, yeah?" I grunted. "Five'll get you ten Baxter thinks differently!"

The one who wasn't Charlie hesitated, and his grip, hitherto vise-tight on my upper arm, went suddenly slack. "Disobeying an Amnesty-bearer is unprecedented," he said carefully.

"So is the theft of the Amnesty!" I shouted in exasperation.

The other one looked at Charlie. "Maybe we ought to call Baxter, just in case."

"In my book," Charlie muttered, "that's not holding a guy incommunicado!"

"The hell it's not," I snorted. "I won't communicate with him. You two guys do it. Do it any way you can square it with your sense of duty. Either tell Baxter you have a man in custody by the name of Jery Delvin or that the Amnesty is in the possession of a blue-eyed blonde girl, and see what he says!"

Two hours later, I was facing the image of a purple-faced Chief Baxter on an interplanetary videoscreen. "Sorry to be so long, Delvin," he said apologetically. "But I'd left orders not to be disturbed. Anyway, I've given the men instructions to return the collapser to you, and an authorization permit for it, in case you meet any more agents."

"Which heaven forbid!" I growled. "No red tape with an Amnesty. Ha!"

"Uh. Yes. So you can continue with your search, Delvin. Have you found anything interesting?"

"Full report when I get back, Baxter," I said. "Right now, I have a date with a beautiful blonde."

"A date?" he choked out. "But—"

"Signing off," I said, and cut the circuit. I belted the collapser into place around my waist, and started off for the city proper. Somewhere in Marsport there was a lovely blonde girl named Snow White, who could do anything, anything at all, and get away with it. Anything but one thing.

She couldn't get within a foot of me again! Not if I had anything to say about it.

8Marsport, the largest—if you excluded the prospecting encampments within a hundred-mile radius of the place—city on the Planet, had grown fast, from the time of its founding in 2014. Originally simply a mining site for the Tri-Planet Refining Corporation, it had spread backward from the area of the original mines in a rough circle, beginning with the monotonous quonset huts of the miners, and modulating in its move toward the perimeter to smart iron-and-adobe structures. Some of these, thanks to the less-than-half Earth's normal gravity, as high as fifteen stories.

The planet, barely half the diameter of Earth and a tenth of Earth's mass, was a minerologist's paradise. The rusty red sands of the Martian desert were almost pure ferrous oxide, a source of both iron for the profitable refineries and oxygen for the inhabitants of Marsport.

Going Los Angeles one ridge better, Marsport was completely circumscribed by high crimson hills, and this natural bowl formation, plus oxygen's heavier-than-air-density, allowed the city to be filled with breathable atmosphere, much as tobacco smoke can lie surging gently within an ashtray if the air in a room is still. This made planetary wind-storms a hazard.

Outside the hills, of course, the air was thin, cold and barely able to support life, being comparable to the biting cold air atop Mount Everest. Human lungs could not breathe it for long without freezing. Naturally, there was a high casualty rate amongst the prospectors, despite their pressurized metal huts and oxygen masks. But uranium, as it had been since the advent of the atomic age, was enormously well-paying to the one miner in twenty to find any in Mars' body breaking hinterlands with its roasting dry heat of day and blood-freezing cold by night.

And then there was parabolite.

This mineral, found in abundance beneath the Martian sands, was, theoretically, worth ten times its weight in gold to the people who might mine it. I say theoretically, because no one had as yet found a way of getting any ore. Paradoxically, the feature which made parabolite so vitally desired was the same feature which prevented anyone from mining it: it was totally indestructible.

The name had been given it by the scientists who studied the three solitary fragments of it found small enough for shipping back to Earth. There was just no way of chipping a piece loose for analysis. The name was due to the oddly shaped molecules which made up this mineral. All of them seemed to be joined atomically into perfect parabolas, no matter which way you came at them. Which meant, in effect, that when anything was brought to bear against the substance, pressure which struck one end of the parabolically curved molecules was retransmitted by the other end, back to the thing putting pressure on it. Result: it "hit back" with a violence equal to that applied to it, and sustained no damage whatsoever to itself. Chemicals were tried when pickaxes had failed, but the substance was inert.

Comments (0)