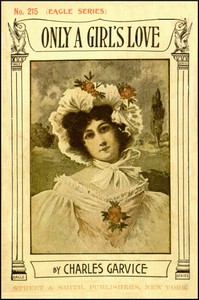

Only a Girl's Love by Charles Garvice (best contemporary novels .TXT) 📗

- Author: Charles Garvice

Book online «Only a Girl's Love by Charles Garvice (best contemporary novels .TXT) 📗». Author Charles Garvice

"Go to her," he said. "She has lied to me. There is something between her and that man. I have seen her for the last time," and before the boy could find a word of expostulation or entreaty, Leycester pushed him aside and went out.

CHAPTER XXXI.Leycester went down the stairs with the uncertain gait of a drunken man, and having reached the open air stood for a moment staring round him as if he were bereft of his senses; as indeed he almost was.

The shock had come so suddenly that it had deprived him of the power of reasoning, of following the thing out to its logical conclusion. As he walked on, threading his way along the crowded thoroughfare, and exciting no little attention and remark by his wild, distraught appearance, he realized that he had lost Stella.

He realized that he had lost the beautiful girl who had stolen into his heart and absorbed his love. And the manner of his losing her made the loss so bitter! That a man, that such a creature as this Jasper Adelstone, should come between them was terrible. If it had been any other, who was in some fashion his own equal—Charlie Guildford, for instance, a gentleman and a nobleman—it would have been bad enough, but he could have understood it. He would have felt that he had been fairly beaten; but Jasper Adelstone!

Then it was so evident that love was not altogether the reason of her treachery and desertion; there was something else; some secret which gave that man a hold over her. He stopped short in the most crowded part of the Strand, and put his hand to his brow and groaned.

To think that his Stella, his beautiful child-love, whom he had deemed an angel for innocence, should share a secret with such a man. And what was it? Was there shame connected with it? He shuddered as the suspicion crossed his mind and smote upon his heart. What had she done to place her so utterly in Jasper Adelstone's hands? What was it? The question harassed and worried him to the exclusion of all other sides of the case.

Was it something that had occurred before he, Leycester, had met her? She had known this Jasper Adelstone before she knew Leycester; but he remembered her speaking of him as a conceited, self-opinioned young man; he remembered the light scorn with which she had described him.

No, it could not have happened thus early. When then? and where was it? He could find no solution to the question; but the terrible result remained, that she had delivered herself, body[210] and soul, into the hands of Jasper Adelstone, and was lost to him, Leycester!

Striking along, careless of where he was going, he found himself at last in Pall Mall. He entered one of his clubs, and went to the smoking-room. There he lit a cigar, and took out the marriage license and looked at it long and absently. If all had gone right, Stella would have been his, if not by this time, a very little later, and they would have gone to Italy, they two, together and alone—with happiness.

But now it was all changed—the cup had been dashed from his lips at the last moment, and by—Jasper Adelstone!

He sat, with the unsmoked cigar in his fingers, his head drooped upon his breast, the nightmare of the secret mystery pressing on his shoulders. It was not only the loss of Stella, it was the feeling that she had deceived him that was so bitter to bear; it was the existence of the secret understanding between the two that so utterly overwhelmed him. He could have married Stella though she had been a beggar in the streets, but he could have no part or lot in the woman who shared a secret with such a one as Jasper Adelstone.

The smoking-room footman hovered about, glancing covertly and curiously at the motionless figure in the deep arm-chair; acquaintances sauntered in and gave him good-bye; but Leycester sat brooding over his sorrow and disappointment, and made no response.

A more miserable young man it would have been impossible to find in all London than this viscount and heir to an earldom, with all his immense wealth and proud hereditary titles.

The afternoon came, hot and sultry, and to him suffocating. The footman, beginning to be seriously alarmed by the quiescence of the silent figure, was just considering whether it was not his duty to bring him some refreshment, or rouse him by offering him the paper, when Leycester rose, much to the man's relief, and walked out.

Within the last few minutes he had decided upon some course of action. He could not stay in London, he could not remain in England; he would go abroad—go right out of the way, and try and forget. He smiled to himself at the word, as if he should ever forget the beautiful face that had lain upon his breast, the exquisite eyes that had poured the lovelight into his, the sweet girl-voice that had murmured its maiden confession in his ear!

He called a cab, and told the man to drive to Waterloo; caught a train, threw himself into a corner of the carriage, and gave himself up to the bitterness of despair.

Dinner was just over when his tall figure passed along the terrace, and the ladies were standing under the drawing-room veranda enjoying the sunset. A little apart from the rest stood Lenore. She was leaning against one of the iron columns, her dress of white cashmere and satin trimmed with pearls standing out daintily and fairy-like against the mass of ferns and flowers behind her.

She was leaning in the most graceful air of abandon, her[211] sunshade lying at her feet, her hands folded with an indolent air of rest on her lap; there was a serene smile upon her lips, a delicate languor in her violet eyes, an altogether at-peace-with-all-the-world expression which was in direct contrast with the faint expression of anxiety which rested on the handsome face of the countess.

Every now and then, as the proud and haughty woman, but anxious mother, chatted and laughed with the women around her, her gaze wandered to the open country with an absent, almost fearful expression, and once, as the sound of a carriage was heard on the drive, she was actually guilty of a start.

But the carriage was only that of one of the guests, and the countess sighed and turned to her duties again. Lenore, with head thrown back, watched her with a lazy smile. She was suffering likewise, but she had something tangible to fear, something definite to hope; the mother knew nothing, but feared all things.

Presently Lady Wyndward happened to come within the scope of Lenore's voice.

"You look tired to-night, dear," she said.

The countess smiled, wearily.

"I will admit a little headache," she said; then she looked at the lovely indolent face. "You look well enough, Lenore!"

Lady Lenore smiled, curiously.

"Do you think so!" she answered. "Suppose I also confessed a headache!"

"I should outdo you even then," said the countess, with a sigh, "for I have a heartache!"

Lenore put out her hand, white and glittering with pearls and diamonds, and laid it on the elder woman's arm with a little caressing gesture peculiar to her.

"Tell me dear," she whispered.

The countess shook her head.

"I cannot," she said, with a sigh. "I scarcely know myself. I am quite in the dark, but I know that something has happened or is happening. You know that Leycester went suddenly yesterday?"

Lady Lenore moved her head in assent.

The countess sighed.

"I am always fearful of him."

Lenore laughed, softly.

"So am I. But I am not fearful on this occasion. Wait until he comes back."

The countess shook her head.

"When will that be? I am afraid not for some time!"

"I think he will come back to-night," said Lenore, with a smile that was too placid to be confident or boastful.

The countess smiled and looked at her.

"You are a strange girl, Lenore," she said. "What makes you think that?"

Lenore turned the bracelet on her arm.

"Something seems to whisper to me that he will come," she said. "Look!" And she just moved her hand toward the terrace.[212] Leycester was coming slowly up the broad stone steps.

Lady Wyndward made a move forward, but Lenore's hand closed over her arm, and she stopped and looked at her.

Lenore shook her head, smiling softly.

"Better not," she murmured, scarcely above her breath. "Not yet. Leave him alone. Something has happened as you surmised. I have such keen eyes, you know, and can see his face."

So could Lady Wyndward by this time, and her own turned white at sight of the pale, haggard face.

"Do not go to him," whispered Lenore, "do not stop him. Leave him alone; it is good advice."

Lady Wyndward felt instinctively that it was, and so that she might not be tempted to disregard it, she turned away and went into the house.

Leycester came along the terrace, and raising his eyes, heavy and clouded, saw the ladies, but he only raised his hat and passed on. Then he came to where the figure in white, glimmering with pearls and diamonds, leaned against the column and he hesitated a moment, but there was no look of invitation in her eyes, only a faint smile, and he merely raised his hat again and passed on; but, half unconsciously, he had taken in the loveliness and grace of the picture that she made, and that was all that she desired for the present.

With heavy steps he crossed the hall, climbed the stairs, and entered his own room.

His man Oliver, who had been waiting for him and hanging about, came in softly, but stole out again at sight of the dusky figure lying wearily on the chair; but presently Leycester called him and he went back.

"Get a bath ready, Oliver," he said, "and pack a portmanteau; we shall leave to-night."

"Very good, my lord," was the quiet response, and then he went to prepare the bath.

Leycester got up and strode to and fro. Though she had never entered his rooms, the apartments seemed full of her; from the easel stared the disfigured Venus which he had daubed out on the first night he had seen her. On the table, in an Etruscan vase of crystal, were some of the wild flowers which her hand had plucked, her lips had pressed. These he took—not fiercely but solemnly—and threw out of the window.

Suddenly there floated upon the air the strains of solemn music. He started. He had almost forgotten Lilian; the great sorrow and misery had almost driven her from his memory. He sat the vase down upon the table, and went to her room; she knew his knock, and bade him come in, still playing.

But as he entered, she stopped suddenly, and the smile which had flown to her face to welcome him disappeared.

"Ley!" she breathed, looking up at his pale, haggard face and dark-rimmed eyes; "what has happened? What is the matter?"

He stood beside her, and bent and kissed her; his lips were dry and burning.

[213]

"Ley! Ley!" she murmured, and put her white arm round his neck to draw him down to her, "what is it?"

Then she scanned him with loving anxiety.

"How tired you look, Ley! Where have you been? Sit down!"

He sank into a low seat at her feet, and motioned to the piano.

"Go on playing," he said.

She started at his hoarse, dry voice, but turned to the piano, and played softly, and presently she knew, rather than saw, that he had hidden his face in his hands.

Then she stopped and bent over him.

"Now tell me, Ley!" she murmured.

He looked up with a bitter smile that cut her to the heart.

"It is soon told, Lil," he said, in a low voice, "and it is only an old, old story!"

"Ley!"

"I can tell you—I could tell only you, Lil—in a very few words. I have loved—and been deceived."

She did not speak, but she put her hand on his head where it lay like a peaceful benediction.

"I have staked my all, all my happiness and peace, upon a cast and have lost. I am very badly hit, and naturally I feel it very badly for a time!"

"Ley!" she murmured, reproachfully, "you must not talk to me like this; speak from your heart."

"I haven't any left, Lil!" he said; "there is only an aching void where my heart used to be. I lost it weeks ago—or was it months or years? I can't tell which now!—and she to whom I gave it, she whom I thought an angel of purity, a dove of innocence, has thrown it in the dirt and trampled upon it!"

"Ley, Ley, you torture me! Of whom are you speaking?"

"Of whom should I be speaking but the one woman the world holds for me?"

"Lenore!" she murmured,

Comments (0)