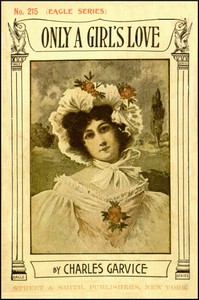

Only a Girl's Love by Charles Garvice (best contemporary novels .TXT) 📗

- Author: Charles Garvice

Book online «Only a Girl's Love by Charles Garvice (best contemporary novels .TXT) 📗». Author Charles Garvice

Sometimes he wondered whether he had been right in yielding her up to Jasper Adelstone so quietly; but as he recalled that morning, and Stella's face and words, he felt that he could not have done otherwise. Yes, he had lost her, she had gone forever, yet he could not forget her. It seemed very strange, even to himself. After all, there were so many beautiful women he could have chosen; some he had been almost in love with, and yet he had forgotten them. What was there about Stella to cling to him so persistently? He remembered every little unconscious trick of voice and manner, the faint little smile that curved her lip, the deep light in the dark eyes as they lifted to his, asking, taking his love. There was a special little trick or mannerism she had, a way of bending her head and looking at him half over her shoulder, that simply haunted him; she came—the vision of her—to the side of his chair and his bed, and looked at him so, and he could see the graceful curve of the delicate neck. Ah, me! ah, me! It was very weak and foolish, perhaps, that a strong man of the world should be held in such thrall by a simple girl, just a girl; but men are made so, and will so be held, when they are strong and true, till the world ends.

It was very slow for Charlie—very slow and very rough, but he was one of those rare friends who stick close in such a time. He fished, and shot, and rode, and walked, and was always cheerful and never obtrusive; but though he never made any remark, he could not but notice that Leycester was in a bad way. He was getting thinner and older looking, and the haggard lines, which the wild town life had begun to draw, deepened.

Lord Charles was beginning to be afraid that the Doone Valley also would fail.

"Ever hear anything of your people, Ley?" he asked one night, as they sat in the living room of the hut. The night was warm for the time of year, and they sat by the open window smoking their pipes, and clad in their shooting suits of woolen mixture.

Leycester was leaning back, his head resting on his hand, his eyes fixed on the starlit sky, his long knickerbockered legs outstretched.

"My people?" he replied, with a little movement as of one waking from a dream. "No. I believe they are in the country somewhere."

"Didn't leave any address for them?"

Leycester shook his head.

"No. I have no doubt they know it, however; Oliver is engaged to Lilian's maid, Jeanette, and doubtless writes to her."

Charles looked at him.

"Getting tired of this, old man?" he asked, quietly.

"No," said Leycester. "Not at all. I can keep it up as long as you like. If you are tired, we will go. Don't imagine that I am insensible to the boredom you are undergoing, Charlie. But I advised you to let me go my way alone, did I not?"

"That's so," was the cheerful response. "But I didn't choose,[242] did I? And I don't now. But all the same, I should like to see you look a little more chippy, Ley."

Leycester looked up at him and smiled, grimly.

"I wonder whether you were ever in any trouble in your life, Charlie," he said.

Lord Charles drained the glass of whisky and water that stood beside him.

"Yes," he said; "but I'm like a duck, it pours off my back, and there I am again."

"I wish I were like a duck!" said Leycester, with bitter self-scorn. "Charlie, you have the misfortune to be tied to a haunted man. I am haunted by the ghost of an old and lost happiness, and I can't get rid of it."

Charlie looked at him and then away.

"I know," he said; "I haven't said anything, but I know. Well, I am not surprised; she is a beautiful creature, and one of the sort to stick in a man's mind. I'm very sorry, old man. There isn't any chance of its coming right?"

"None whatever," said Leycester, "and that is why I am a great fool in clinging to it."

He got up and began to pace the room, and the color mounted to his haggard face.

"I cannot—I cannot shake it off. Charlie, I despise myself; and yet, no, no, to love her once was to love her for always—to the end."

"There's another man, of course," said Lord Charles. "Didn't it occur to you to—well, to break his neck, or put a bullet through him, or get him appointed governor of the Cannibal Islands, Ley? That used to be your style."

Leycester smiled grimly.

"This man cannot be dealt with in any one of those excellent ways, Charlie," he said.

"If it's the man I suppose, that fellow Jasper Addled egg—no, Adelstone, I should have tried the first at any rate," said Lord Charles, emphatically.

Leycester shook his head.

"It's a bad business," he said, curtly, "and there is no way of making it a good one. I will go to bed. What shall we do to-morrow?" and he sighed.

Lord Charles laid his hand on his arm and kept him for a moment.

"You want rousing, Ley," he said. "Rousing, that's it! Let's have the horses to-morrow and take a big spin; anywhere, nowhere, it doesn't matter. We'll go while they can."

Ley nodded.

"Anything you like," he said, and went out.

Lord Charles called to Oliver, who was standing outside smoking a cigar—he was quite as particular about the brand as his master:

"Where did you say the earl and countess were, Oliver?" he asked.

"At Darlingford Court, my lord."

[243]

"How far is it from here? Can we do it to-morrow with the nags?"

Oliver thought a moment.

"If they are taken steadily, my lord; not as his lordship has been riding lately; as if the horse were cast iron and his own neck too."

Lord Charles nodded.

"All right," he said, "we'll do it. Lord Leycester wants a change again, Oliver."

Oliver nodded.

"We'll run over there. Needn't say anything to his lordship—you understand."

Oliver quite understood, and went off to the small stable to see about the horses, and Lord Charles went to bed chuckling over his little plot.

When they started in the morning, Leycester asked no questions and displayed the supremest indifference to the route, and Lord Charles, affecting a little indecision, made for the road to which Oliver had directed him.

The two friends rode almost in silence as was their wont, Leycester paying very little attention to anything excepting his horse, and scarcely noticing the fact that Lord Charles seemed very decided about the route.

Once he asked a question; it was when the evening was drawing in, and they were still riding, as to their destination, but Lord Charles evaded it:

"We shall get somewhere, I expect," he said quietly. "There is sure to be an inn—or something."

And Leycester was content.

About dusk they reached the entrance to Darlingford. There was no village, no inn. Leycester pulled up and waited indifferently.

"What do we do now?" he asked.

Lord Charles laughed, but rather consciously.

"Look here," he said: "I know some people who have got this place. We'd better ride up and get a night's lodging."

Leycester looked at him, and smiled suddenly.

"Isn't this rather transparent, Charlie?" he said, calmly. "Of course you intended to come here from the very start, very well."

"Well, I suspect I did," said Lord Charles. "You don't mind?"

Leycester shook his head.

"Not at all. They will let us go to bed, I suppose. You can tell them that you are traveling keeper to a melancholy monomaniac, and they'll leave me alone. Mind, we start in the morning."

"All right," said Lord Charles, chuckling inwardly—"of course; quite so. Come on."

They rode up the avenue, and to the front of a straggling stone mansion, and a groom came forward and took their horses. Lord Charles drew Leycester's arm within his.

"We shall be sure of a welcome."

[244]

And he walked up a broad flight of steps.

But Leycester stopped suddenly; for a figure came out of one of the windows, and stood looking down at them.

It was a woman, gracefully and beautifully dressed in some softly-hued evening robe. He could not see her face, but he knew her, and turned almost angrily to Lord Charles. But Lord Charles had slipped away, muttering something about the horses, and Leycester went slowly up.

Lenore—it was she—awaited his approach all unconsciously. She could not see him as plainly as he saw her, and she took him for some strange chance visitor.

But as he came up and stood in front of her she recognized him, and, with a low cry, she moved toward him, her lovely face suddenly smitten pale, her violet eyes fixed on him yearningly.

"Leycester!" she said, and overcome for the moment by the suddenness of his presence, she staggered slightly.

He could do no less than put his arm round her, for he thought she would have fallen, and as he did so his heart reproached him, for the one word "Leycester," and the tone told her story. His mother was right. She loved him.

"Lenore," he said, and his deep, grave, musical voice trembled slightly. She lay back in his arms for a moment, looking up at him with an expression of helpless resignation in her eyes, her lovely face revealed in the light which poured from the window full upon her.

"Lenore," he said, huskily, "what—what is this?"

Her eyes closed for a moment, and a faint thrill ran through her, then she regained her composure, and putting him gently from her, she laughed softly.

"It was your fault," she said, the exquisite voice tremulous with emotion. "Why do you steal upon us like a thief in the night, or—like a ghost? You frightened me."

He stood and looked at her, and put his hand to his brow. He was but mortal, was but a man with a man's passions, a man's susceptibility to woman's loveliness, and he knew that she loved him.

"I——" he said, then stopped. "I did not know. Charlie brought me here. Who are here?"

"They are all here," she said, her eyes downcast. "I will go and tell them lest you frighten them as you frightened me," and she stole away from him like a shadow.

He stood, his hands thrust in his pockets, his eyes fixed on the ground.

She was very beautiful, and she loved him. Why should he not make her happy? make one person happy at least? Not only one person, but his mother, and Lilian—all of them. As for himself, well! one woman was as good as another, seeing that he had lost his darling! And this other was the best and rarest of all that were left.

"Leycester!"

It was his mother's voice. He turned and kissed her; she was not frightened, she did not even kiss him, but she put her[245] hand on his arm, and he felt it tremble, and the way she spoke the word told of all her past sorrow at his absence, and her joy at his return.

"You have come back to us!" she said, and that was all.

"Yes, I have come back!" he said, with something like a sigh.

She looked at him, and the mother's heart was wrung.

"Have you been ill, Leycester?" she asked, quietly.

"Ill, no," he said, then he laughed a strange laugh. "Do I look so seedy, my lady?"

"You look——" she began, with sad bitterness, then she stopped. "Come in."

He followed her in, but at the door he paused and looked out at the night. As he did so, the vision of the slim, graceful girl, of his lost darling, seemed to float before him, with pale face, and wistful, reproachful eyes. He put up his hand with a strange, despairing gesture, and his lips moved.

"Good-bye!" he murmured. "Oh, my lost love, good-bye!"

CHAPTER XXXVII.Lord Charles' little plot had succeeded beyond his expectation. He had restored the prodigal and shared the fatted calf, as he deserved to do. Although it was known all over the house, in five minutes, that Lord Leycester, the heir, had returned, there was no fuss, only a pleasant little simmer of welcome and satisfaction.

The countess had gone to the earl, who was dressing for dinner, to tell him the news.

"Leycester has returned," she said.

The earl started and sent his valet away.

"What!"

"Yes, he has come back to us," she said, sinking into a seat.

"Where from?" he demanded.

She shook her head.

"I don't know. I don't want

Comments (0)