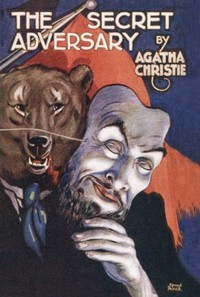

The Secret Adversary by Agatha Christie (great novels of all time txt) 📗

- Author: Agatha Christie

Book online «The Secret Adversary by Agatha Christie (great novels of all time txt) 📗». Author Agatha Christie

“Oh!” cried Tuppence. “Then you know where she is?”

“No!” Mr. Hersheimmer brought down his fist with a bang on the table. “I’m darned if I do! Don’t you?”

“We advertised to receive information, not to give it,” said Tuppence severely.

“I guess I know that. I can read. But I thought maybe it was her back history you were after, and that you’d know where she was now?”

“Well, we wouldn’t mind hearing her back history,” said Tuppence guardedly.

But Mr. Hersheimmer seemed to grow suddenly suspicious.

“See here,” he declared. “This isn’t Sicily! No demanding ransom or threatening to crop her ears if I refuse. These are the British Isles, so quit the funny business, or I’ll just sing out for that beautiful big British policeman I see out there in Piccadilly.”

Tommy hastened to explain.

“We haven’t kidnapped your cousin. On the contrary, we’re trying to find her. We’re employed to do so.”

Mr. Hersheimmer leant back in his chair.

“Put me wise,” he said succinctly.

Tommy fell in with this demand in so far as he gave him a guarded version of the disappearance of Jane Finn, and of the possibility of her having been mixed up unawares in “some political show.” He alluded to Tuppence and himself as “private inquiry agents” commissioned to find her, and added that they would therefore be glad of any details Mr. Hersheimmer could give them.

That gentleman nodded approval.

“I guess that’s all right. I was just a mite hasty. But London gets my goat! I only know little old New York. Just trot out your questions and I’ll answer.”

For the moment this paralysed the Young Adventurers, but Tuppence, recovering herself, plunged boldly into the breach with a reminiscence culled from detective fiction.

“When did you last see the dece—your cousin, I mean?”

“Never seen her,” responded Mr. Hersheimmer.

“What?” demanded Tommy, astonished.

Hersheimmer turned to him.

“No, sir. As I said before, my father and her mother were brother and sister, just as you might be”—Tommy did not correct this view of their relationship—“but they didn’t always get on together. And when my aunt made up her mind to marry Amos Finn, who was a poor school teacher out West, my father was just mad! Said if he made his pile, as he seemed in a fair way to do, she’d never see a cent of it. Well, the upshot was that Aunt Jane went out West and we never heard from her again.

“The old man did pile it up. He went into oil, and he went into steel, and he played a bit with railroads, and I can tell you he made Wall Street sit up!” He paused. “Then he died—last fall—and I got the dollars. Well, would you believe it, my conscience got busy! Kept knocking me up and saying: What about your Aunt Jane, way out West? It worried me some. You see, I figured it out that Amos Finn would never make good. He wasn’t the sort. End of it was, I hired a man to hunt her down. Result, she was dead, and Amos Finn was dead, but they’d left a daughter—Jane—who’d been torpedoed in the Lusitania on her way to Paris. She was saved all right, but they didn’t seem able to hear of her over this side. I guessed they weren’t hustling any, so I thought I’d come along over, and speed things up. I phoned Scotland Yard and the Admiralty first thing. The Admiralty rather choked me off, but Scotland Yard were very civil—said they would make inquiries, even sent a man round this morning to get her photograph. I’m off to Paris to-morrow, just to see what the Prefecture is doing. I guess if I go to and fro hustling them, they ought to get busy!”

The energy of Mr. Hersheimmer was tremendous. They bowed before it.

“But say now,” he ended, “you’re not after her for anything? Contempt of court, or something British? A proud-spirited young American girl might find your rules and regulations in war time rather irksome, and get up against it. If that’s the case, and there’s such a thing as graft in this country, I’ll buy her off.”

Tuppence reassured him.

“That’s good. Then we can work together. What about some lunch? Shall we have it up here, or go down to the restaurant?”

Tuppence expressed a preference for the latter, and Julius bowed to her decision.

Oysters had just given place to Sole Colbert when a card was brought to Hersheimmer.

“Inspector Japp, C.I.D. Scotland Yard again. Another man this time. What does he expect I can tell him that I didn’t tell the first chap? I hope they haven’t lost that photograph. That Western photographer’s place was burned down and all his negatives destroyed—this is the only copy in existence. I got it from the principal of the college there.”

An unformulated dread swept over Tuppence.

“You—you don’t know the name of the man who came this morning?”

“Yes, I do. No, I don’t. Half a second. It was on his card. Oh, I know! Inspector Brown. Quiet, unassuming sort of chap.”

A PLAN OF CAMPAIGN

A veil might with profit be drawn over the events of the next half-hour. Suffice it to say that no such person as “Inspector Brown” was known to Scotland Yard. The photograph of Jane Finn, which would have been of the utmost value to the police in tracing her, was lost beyond recovery. Once again “Mr. Brown” had triumphed.

The immediate result of this set-back was to effect a rapprochement between Julius Hersheimmer and the Young Adventurers. All barriers went down with a crash, and Tommy and Tuppence felt they had known the young American all their lives. They abandoned the discreet reticence of “private inquiry agents,” and revealed to him the whole history of the joint venture, whereat the young man declared himself “tickled to death.”

He turned to Tuppence at the close of the narration.

“I’ve always had a kind of idea that English girls were just a mite moss-grown. Old-fashioned and sweet, you know, but scared to move round without a footman or a maiden aunt. I guess I’m a bit behind the times!”

The upshot of these confidential relations was that Tommy and Tuppence took up their abode forthwith at the Ritz, in order, as Tuppence put it, to keep in touch with Jane Finn’s only living relation. “And put like that,” she added confidentially to Tommy, “nobody could boggle at the expense!”

Nobody did, which was the great thing.

“And now,” said the young lady on the morning after their installation, “to work!”

Mr. Beresford put down the Daily Mail, which he was reading, and applauded with somewhat unnecessary vigour. He was politely requested by his colleague not to be an ass.

“Dash it all, Tommy, we’ve got to do something for our money.”

Tommy sighed.

“Yes, I fear even the dear old Government will not support us at the Ritz in idleness for ever.”

“Therefore, as I said before, we must do something.”

“Well,” said Tommy, picking up the Daily Mail again, “do it. I shan’t stop you.”

“You see,” continued Tuppence. “I’ve been thinking——”

She was interrupted by a fresh bout of applause.

“It’s all very well for you to sit there being funny, Tommy. It would do you no harm to do a little brain work too.”

“My union, Tuppence, my union! It does not permit me to work before 11 a.m.”

“Tommy, do you want something thrown at you? It is absolutely essential that we should without delay map out a plan of campaign.”

“Hear, hear!”

“Well, let’s do it.”

Tommy laid his paper finally aside. “There’s something of the simplicity of the truly great mind about you, Tuppence. Fire ahead. I’m listening.”

“To begin with,” said Tuppence, “what have we to go upon?”

“Absolutely nothing,” said Tommy cheerily.

“Wrong!” Tuppence wagged an energetic finger. “We have two distinct clues.”

“What are they?”

“First clue, we know one of the gang.”

“Whittington?”

“Yes. I’d recognize him anywhere.”

“Hum,” said Tommy doubtfully, “I don’t call that much of a clue. You don’t know where to look for him, and it’s about a thousand to one against your running against him by accident.”

“I’m not so sure about that,” replied Tuppence thoughtfully. “I’ve often noticed that once coincidences start happening they go on happening in the most extraordinary way. I dare say it’s some natural law that we haven’t found out. Still, as you say, we can’t rely on that. But there are places in London where simply every one is bound to turn up sooner or later. Piccadilly Circus, for instance. One of my ideas was to take up my stand there every day with a tray of flags.”

“What about meals?” inquired the practical Tommy.

“How like a man! What does mere food matter?”

“That’s all very well. You’ve just had a thundering good breakfast. No one’s got a better appetite than you have, Tuppence, and by tea-time you’d be eating the flags, pins and all. But, honestly, I don’t think much of the idea. Whittington mayn’t be in London at all.”

“That’s true. Anyway, I think clue No. 2 is more promising.”

“Let’s hear it.”

“It’s nothing much. Only a Christian name—Rita. Whittington mentioned it that day.”

“Are you proposing a third advertisement: Wanted, female crook, answering to the name of Rita?”

“I am not. I propose to reason in a logical manner. That man, Danvers, was shadowed on the way over, wasn’t he? And it’s more likely to have been a woman than a man——”

“I don’t see that at all.”

“I am absolutely certain that it would be a woman, and a good-looking one,” replied Tuppence calmly.

“On these technical points I bow to your decision,” murmured Mr. Beresford.

“Now, obviously this woman, whoever she was, was saved.”

“How do you make that out?”

“If she wasn’t, how would they have known Jane Finn had got the papers?”

“Correct. Proceed, O Sherlock!”

“Now there’s just a chance, I admit it’s only a chance, that this woman may have been ‘Rita.’”

“And if so?”

“If so, we’ve got to hunt through the survivors of the Lusitania till we find her.”

“Then the first thing is to get a list of the survivors.”

“I’ve got it. I wrote a long list of things I wanted to know, and sent it to Mr. Carter. I got his reply this morning, and among other things it encloses the official statement of those saved from the Lusitania. How’s that for clever little Tuppence?”

“Full marks for industry, zero for modesty. But the great point is, is there a ‘Rita’ on the list?”

“That’s just what I don’t know,” confessed Tuppence.

“Don’t know?”

“Yes. Look here.” Together they bent over the list. “You see, very few Christian names are given. They’re nearly all Mrs. or Miss.”

Tommy nodded.

“That complicates matters,” he murmured thoughtfully.

Tuppence gave her characteristic “terrier” shake.

“Well, we’ve just got to get down to it, that’s all. We’ll start with the London area. Just note down the addresses of any of the females who live in London or roundabout, while I put on my hat.”

Five minutes later the young couple emerged into Piccadilly, and a few seconds later a taxi was bearing them to The Laurels, Glendower Road, N.7, the residence of Mrs. Edgar Keith, whose name figured first in a list of seven reposing in Tommy’s pocket-book.

The Laurels was a dilapidated house, standing back from the road with a few grimy bushes to support the fiction of a front garden. Tommy paid off the taxi, and accompanied Tuppence to the front door bell. As she was about to ring it, he arrested her hand.

“What are you going to say?”

“What am I going to say? Why, I shall say—Oh dear, I don’t know. It’s very awkward.”

“I thought as much,” said Tommy with satisfaction. “How like a woman! No foresight! Now just stand aside, and see how easily the mere male deals with the situation.” He pressed the bell. Tuppence withdrew to a suitable spot.

A slatternly looking servant, with an extremely dirty face and a pair of eyes that did not match, answered the door.

Tommy had produced a notebook and pencil.

“Good morning,” he said briskly and cheerfully. “From the Hampstead Borough Council. The new Voting Register. Mrs. Edgar Keith lives here, does she not?”

“Yaas,” said the servant.

“Christian name?” asked Tommy, his pencil poised.

“Missus’s? Eleanor Jane.”

“Eleanor,” spelt Tommy. “Any sons or daughters over twenty-one?”

“Naow.”

“Thank you.” Tommy closed the notebook with a brisk snap. “Good morning.”

The servant volunteered her first remark:

“I thought perhaps as you’d come about the gas,” she observed cryptically, and shut the door.

Tommy rejoined his accomplice.

“You see, Tuppence,” he observed. “Child’s play to the masculine mind.”

“I don’t mind admitting that for once you’ve scored handsomely. I should never have thought of that.”

“Good wheeze, wasn’t it? And we can repeat it ad lib.”

Lunch-time found the young couple attacking a steak and chips in an obscure hostelry with avidity. They had collected a Gladys Mary and a Marjorie, been baffled by one change of address, and had been forced to listen to a long lecture on universal suffrage from a

Comments (0)