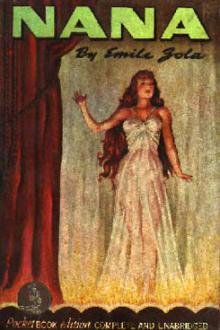

Nana - Émile Zola (good books to read for young adults txt) 📗

- Author: Émile Zola

- Performer: -

Book online «Nana - Émile Zola (good books to read for young adults txt) 📗». Author Émile Zola

revoir!”

And he entered the room, which was narrow and low-pitched and half

filled with a great pair of scales. It was like a waiting room in a

suburban station, and Nana was again hugely disillusioned, for she

had been picturing to herself something on a very vast scale, a

monumental machine, in fact, for weighing horses. Dear me, they

only weighed the jockeys! Then it wasn’t worth while making such a

fuss with their weighing! In the scale a jockey with an idiotic

expression was waiting, harness on knee, till a stout man in a frock

coat should have done verifying his weight. At the door a stable

help was holding a horse, Cosinus, round which a silent and deeply

interested throng was clustering.

The course was about to be cleared. Labordette hurried Nana but

retraced his steps in order to show her a little man talking with

Vandeuvres at some distance from the rest.

“Dear me, there’s Price!” he said.

“Ah yes, the man who’s mounting me,” she murmured laughingly.

And she declared him to be exquisitely ugly. All jockeys struck her

as looking idiotic, doubtless, she said, because they were prevented

from growing bigger. This particular jockey was a man of forty, and

with his long, thin, deeply furrowed, hard, dead countenance, he

looked like an old shriveled-up child. His body was knotty and so

reduced in size that his blue jacket with its white sleeves looked

as if it had been thrown over a lay figure.

“No,” she resumed as she walked away, “he would never make me very

happy, you know.”

A mob of people were still crowding the course, the turf of which

had been wet and trampled on till it had grown black. In front of

the two telegraphs, which hung very high up on their cast-iron

pillars, the crowd were jostling together with upturned faces,

uproariously greeting the numbers of the different horses as an

electric wire in connection with the weighing room made them appear.

Gentlemen were pointing at programs: Pichenette had been scratched

by his owner, and this caused some noise. However, Nana did not do

more than cross over the course on Labordette’s arm. The bell

hanging on the flagstaff was ringing persistently to warn people to

leave the course.

“Ah, my little dears,” she said as she got up into her landau again,

“their enclosure’s all humbug!”

She was welcomed with acclamation; people around her clapped their

hands.

“Bravo, Nana! Nana’s ours again!”

What idiots they were, to be sure! Did they think she was the sort

to cut old friends? She had come back just at the auspicious

moment. Now then, ‘tenshun! The race was beginning! And the

champagne was accordingly forgotten, and everyone left off drinking.

But Nana was astonished to find Gaga in her carriage, sitting with

Bijou and Louiset on her knees. Gaga had indeed decided on this

course of action in order to be near La Faloise, but she told Nana

that she had been anxious to kiss Baby. She adored children.

“By the by, what about Lili?” asked Nana. “That’s certainly she

over there in that old fellow’s brougham. They’ve just told me

something very nice!”

Gaga had adopted a lachrymose expression.

“My dear, it’s made me ill,” she said dolorously. “Yesterday I had

to keep my bed, I cried so, and today I didn’t think I should be

able to come. You know what my opinions were, don’t you? I didn’t

desire that kind of thing at all. I had her educated in a convent

with a view to a good marriage. And then to think of the strict

advice she had and the constant watching! Well, my dear, it was she

who wished it. We had such a scene—tears—disagreeable speeches!

It even got to such a point that I caught her a box on the ear. She

was too much bored by existence, she said; she wanted to get out of

it. By and by, when she began to say, ”Tisn’t you, after all,

who’ve got the right to prevent me,’ I said to her: ‘you’re a

miserable wretch; you’re bringing dishonor upon us. Begone!’ And

it was done. I consented to arrange about it. But my last hope’s

blooming well blasted, and, oh, I used to dream about such nice

things!”

The noise of a quarrel caused them to rise. It was Georges in the

act of defending Vandeuvres against certain vague rumors which were

circulating among the various groups.

“Why should you say that he’s laying off his own horse?” the young

man was exclaiming. “Yesterday in the Salon des Courses he took the

odds on Lusignan for a thousand louis.”

“Yes, I was there,” said Philippe in affirmation of this. “And he

didn’t put a single louis on Nana. If the betting’s ten to one

against Nana he’s got nothing to win there. It’s absurd to imagine

people are so calculating. Where would his interest come in?”

Labordette was listening with a quiet expression. Shrugging his

shoulders, he said:

“Oh, leave them alone; they must have their say. The count has

again laid at least as much as five hundred louis on Lusignan, and

if he’s wanted Nana to run to a hundred louis it’s because an owner

ought always to look as if he believes in his horses.”

“Oh, bosh! What the deuce does that matter to us?” shouted La

Faloise with a wave of his arms. “Spirit’s going to win! Down with

France—bravo, England!”

A long shiver ran through the crowd, while a fresh peal from the

bell announced the arrival of the horses upon the racecourse. At

this Nana got up and stood on one of the seats of her carriage so as

to obtain a better view, and in so doing she trampled the bouquets

of roses and myosotis underfoot. With a sweeping glance she took in

the wide, vast horizon. At this last feverish moment the course was

empty and closed by gray barriers, between the posts of which stood

a line of policemen. The strip of grass which lay muddy in front of

her grew brighter as it stretched away and turned into a tender

green carpet in the distance. In the middle landscape, as she

lowered her eyes, she saw the field swarming with vast numbers of

people, some on tiptoe, others perched on carriages, and all heaving

and jostling in sudden passionate excitement.

Horses were neighing; tent canvases flapped, while equestrians urged

their hacks forward amid a crowd of pedestrians rushing to get

places along the barriers. When Nana turned in the direction of the

stands on the other side the faces seemed diminished, and the dense

masses of heads were only a confused and motley array, filling

gangways, steps and terraces and looming in deep, dark, serried

lines against the sky. And beyond these again she over looked the

plain surrounding the course. Behind the ivy-clad mill to the

right, meadows, dotted over with great patches of umbrageous wood,

stretched away into the distance, while opposite to her, as far as

the Seine flowing at the foot of a hill, the avenues of the park

intersected one another, filled at that moment with long, motionless

files of waiting carriages; and in the direction of Boulogne, on the

left, the landscape widened anew and opened out toward the blue

distances of Meudon through an avenue of paulownias, whose rosy,

leafless tops were one stain of brilliant lake color. People were

still arriving, and a long procession of human ants kept coming

along the narrow ribbon of road which crossed the distance, while

very far away, on the Paris side, the nonpaying public, herding like

sheep among the wood, loomed in a moving line of little dark spots

under the trees on the skirts of the Bois.

Suddenly a cheering influence warmed the hundred thousand souls who

covered this part of the plain like insects swarming madly under the

vast expanse of heaven. The sun, which had been hidden for about a

quarter of an hour, made his appearance again and shone out amid a

perfect sea of light. And everything flamed afresh: the women’s

sunshades turned into countless golden targets above the heads of

the crowd. The sun was applauded, saluted with bursts of laughter.

And people stretched their arms out as though to brush apart the

clouds.

Meanwhile a solitary police officer advanced down the middle of the

deserted racecourse, while higher up, on the left, a man appeared

with a red flag in his hand.

“It’s the starter, the Baron de Mauriac,” said Labordette in reply

to a question from Nana. All round the young woman exclamations

were bursting from the men who were pressing to her very carriage

step. They kept up a disconnected conversation, jerking out phrases

under the immediate influence of passing impressions. Indeed,

Philippe and Georges, Bordenave and La Faloise, could not be quiet.

“Don’t shove! Let me see! Ah, the judge is getting into his box.

D’you say it’s Monsieur de Souvigny? You must have good eyesight—

eh?—to be able to tell what half a head is out of a fakement like

that! Do hold your tongue—the banner’s going up. Here they are—

‘tenshun! Cosinus is the first!”

A red and yellow banner was flapping in mid-air at the top of a

mast. The horses came on the course one by one; they were led by

stableboys, and the jockeys were sitting idle-handed in the saddles,

the sunlight making them look like bright dabs of color. After

Cosinus appeared Hazard and Boum. Presently a murmur of approval

greeted Spirit, a magnificent big brown bay, the harsh citron color

and black of whose jockey were cheerlessly Britannic. Valerio II

scored a success as he came in; he was small and very lively, and

his colors were soft green bordered with pink. The two Vandeuvres

horses were slow to make their appearance, but at last, in

Frangipane’s rear, the blue and white showed themselves. But

Lusignan, a very dark bay of irreproachable shape, was almost

forgotten amid the astonishment caused by Nana. People had not seen

her looking like this before, for now the sudden sunlight was dyeing

the chestnut filly the brilliant color of a girl’s red-gold hair.

She was shining in the light like a new gold coin; her chest was

deep; her head and neck tapered lightly from the delicate, high-strung line of her long back.

“Gracious, she’s got my hair!” cried Nana in an ecstasy. “You bet

you know I’m proud of it!”

The men clambered up on the landau, and Bordenave narrowly escaped

putting his foot on Louiset, whom his mother had forgotten. He took

him up with an outburst of paternal grumbling and hoisted him on his

shoulder, muttering at the same time:

“The poor little brat, he must be in it too! Wait a bit, I’ll show

you Mamma. Eh? Look at Mummy out there.”

And as Bijou was scratching his legs, he took charge of him, too,

while Nana, rejoicing in the brute that bore her name, glanced round

at the other women to see how they took it. They were all raging

madly. Just then on the summit of her cab the Tricon, who had not

moved till that moment, began waving her hand and giving her

bookmaker her orders above the heads of the crowd. Her instinct had

at last prompted her; she was backing Nana.

La Faloise meanwhile was making an insufferable noise. He was

getting wild over Frangipane.

“I’ve an inspiration,” he kept shouting. “Just look at Frangipane.

What an action, eh? I back Frangipane at eight to one. Who’ll take

me?”

“Do keep quiet now,” said Labordette at last. “You’ll be sorry for

Comments (0)