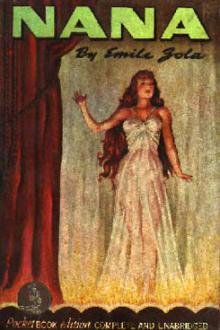

Nana - Émile Zola (good books to read for young adults txt) 📗

- Author: Émile Zola

- Performer: -

Book online «Nana - Émile Zola (good books to read for young adults txt) 📗». Author Émile Zola

“Well, yes, I’ve done wrong. It’s very bad what I did. You see I’m

sorry for my fault. It makes me grieve very much because it annoys

you. Come now, be nice, too, and forgive me.”

She had crouched down at his feet and was striving to catch his eye

with a look of tender submission. She was fain to know whether he

was very vexed with her. Presently, as he gave a long sigh and

seemed to recover himself, she grew more coaxing and with grave

kindness of manner added a final reason:

“You see, dearie, you must try and understand how it is: I can’t

refuse it to my poor friends.”

The count consented to give way and only insisted that Georges

should be dismissed once for all. But all his illusions had

vanished, and he no longer believed in her sworn fidelity. Next day

Nana would deceive him anew, and he only remained her miserable

possessor in obedience to a cowardly necessity and to terror at the

thought of living without her.

This was the epoch in her existence when Nana flared upon Paris with

redoubled splendor. She loomed larger than heretofore on the

horizon of vice and swayed the town with her impudently flaunted

splendor and that contempt of money which made her openly squander

fortunes. Her house had become a sort of glowing smithy, where her

continual desires were the flames and the slightest breath from her

lips changed gold into fine ashes, which the wind hourly swept away.

Never had eye beheld such a rage of expenditure. The great house

seemed to have been built over a gulf in which men—their worldly

possessions, their fortunes, their very names—were swallowed up

without leaving even a handful of dust behind them. This courtesan,

who had the tastes of a parrot and gobbled up radishes and burnt

almonds and pecked at the meat upon her plate, had monthly table

bills amounting to five thousand francs. The wildest waste went on

in the kitchen: the place, metaphorically speaking was one great

river which stove in cask upon cask of wine and swept great bills

with it, swollen by three or four successive manipulators.

Victorine and Francois reigned supreme in the kitchen, whither they

invited friends. In addition to these there was quite a little

tribe of cousins, who were cockered up in their homes with cold

meats and strong soup. Julien made the tradespeople give him

commissions, and the glaziers never put up a pane of glass at a cost

of a franc and a half but he had a franc put down to himself.

Charles devoured the horses’ oats and doubled the amount of their

provender, reselling at the back door what came in at the carriage

gate, while amid the general pillage, the sack of the town after the

storm, Zoe, by dint of cleverness, succeeded in saving appearances

and covering the thefts of all in order the better to slur over and

make good her own. But the household waste was worse than the

household dishonesty. Yesterday’s food was thrown into the gutter,

and the collection of provisions in the house was such that the

servants grew disgusted with it. The glass was all sticky with

sugar, and the gas burners flared and flared till the rooms seemed

ready to explode. Then, too, there were instances of negligence and

mischief and sheer accident—of everything, in fact, which can

hasten the ruin of a house devoured by so many mouths. Upstairs in

Madame’s quarters destruction raged more fiercely still. Dresses,

which cost ten thousand francs and had been twice worn, were sold by

Zoe; jewels vanished as though they had crumbled deep down in their

drawers; stupid purchases were made; every novelty of the day was

brought and left to lie forgotten in some corner the morning after

or swept up by ragpickers in the street. She could not see any very

expensive object without wanting to possess it, and so she

constantly surrounded herself with the wrecks of bouquets and costly

knickknacks and was the happier the more her passing fancy cost.

Nothing remained intact in her hands; she broke everything, and this

object withered, and that grew dirty in the clasp of her lithe white

fingers. A perfect heap of nameless debris, of twisted shreds and

muddy rags, followed her and marked her passage. Then amid this

utter squandering of pocket money cropped up a question about the

big bills and their settlement. Twenty thousand francs were due to

the modiste, thirty thousand to the linen draper, twelve thousand to

the bootmaker. Her stable devoured fifty thousand for her, and in

six months she ran up a bill of a hundred and twenty thousand francs

at her ladies’ tailor. Though she had not enlarged her scheme of

expenditure, which Labordette reckoned at four hundred thousand

francs on an average, she ran up that same year to a million. She

was herself stupefied by the amount and was unable to tell whither

such a sum could have gone. Heaps upon heaps of men, barrowfuls of

gold, failed to stop up the hole, which, amid this ruinous luxury,

continually gaped under the floor of her house.

Meanwhile Nana had cherished her latest caprice. Once more

exercised by the notion that her room needed redoing, she fancied

she had hit on something at last. The room should be done in velvet

of the color of tea roses, with silver buttons and golden cords,

tassels and fringes, and the hangings should be caught up to the

ceiling after the manner of a tent. This arrangement ought to be

both rich and tender, she thought, and would form a splendid

background to her blonde vermeil-tinted skin. However, the bedroom

was only designed to serve as a setting to the bed, which was to be

a dazzling affair, a prodigy. Nana meditated a bed such as had

never before existed; it was to be a throne, an altar, whither Paris

was to come in order to adore her sovereign nudity. It was to be

all in gold and silver beaten work—it should suggest a great piece

of jewelry with its golden roses climbing on a trelliswork of

silver. On the headboard a band of Loves should peep forth laughing

from amid the flowers, as though they were watching the voluptuous

dalliance within the shadow of the bed curtains. Nana had applied

to Labordette who had brought two goldsmiths to see her. They were

already busy with the designs. The bed would cost fifty thousand

francs, and Muffat was to give it her as a New Year’s present.

What most astonished the young woman was that she was endlessly

short of money amid a river of gold, the tide of which almost

enveloped her. On certain days she was at her wit’s end for want of

ridiculously small sums—sums of only a few louis. She was driven

to borrow from Zoe, or she scraped up cash as well as she could on

her own account. But before resignedly adopting extreme measures

she tried her friends and in a joking sort of way got the men to

give her all they had about them, even down to their coppers. For

the last three months she had been emptying Philippe’s pockets

especially, and now on days of passionate enjoyment he never came

away but he left his purse behind him. Soon she grew bolder and

asked him for loans of two hundred francs, three hundred francs—

never more than that—wherewith to pay the interest of bills or to

stave off outrageous debts. And Philippe, who in July had been

appointed paymaster to his regiment, would bring the money the day

after, apologizing at the same time for not being rich, seeing that

good Mamma Hugon now treated her sons with singular financial

severity. At the close of three months these little oft-renewed

loans mounted up to a sum of ten thousand francs. The captain still

laughed his hearty-sounding laugh, but he was growing visibly

thinner, and sometimes he seemed absent-minded, and a shade of

suffering would pass over his face. But one look from Nana’s eyes

would transfigure him in a sort of sensual ecstasy. She had a very

coaxing way with him and would intoxicate him with furtive kisses

and yield herself to him in sudden fits of self-abandonment, which

tied him to her apron strings the moment he was able to escape from

his military duties.

One evening, Nana having announced that her name, too, was Therese

and that her fete day was the fifteenth of October, the gentlemen

all sent her presents. Captain Philippe brought his himself; it was

an old comfit dish in Dresden china, and it had a gold mount. He

found her alone in her dressing room. She had just emerged from the

bath, had nothing on save a great red-and-white flannel bathing wrap

and was very busy examining her presents, which were ranged on a

table. She had already broken a rock-crystal flask in her attempts

to unstopper it.

“Oh, you’re too nice!” she said. “What is it? Let’s have a peep!

What a baby you are to spend your pennies in little fakements like

that!”

She scolded him, seeing that he was not rich, but at heart she was

delighted to see him spending his whole substance for her. Indeed,

this was the only proof of love which had power to touch her.

Meanwhile she was fiddling away at the comfit dish, opening it and

shutting it in her desire to see how it was made.

“Take care,” he murmured, “it’s brittle.”

But she shrugged her shoulders. Did he think her as clumsy as a

street porter? And all of a sudden the hinge came off between her

fingers and the lid fell and was broken. She was stupefied and

remained gazing at the fragments as she cried:

“Oh, it’s smashed!”

Then she burst out laughing. The fragments lying on the floor

tickled her fancy. Her merriment was of the nervous kind, the

stupid, spiteful laughter of a child who delights in destruction.

Philippe had a little fit of disgust, for the wretched girl did not

know what anguish this curio had cost him. Seeing him thoroughly

upset, she tried to contain herself.

“Gracious me, it isn’t my fault! It was cracked; those old things

barely hold together. Besides, it was the cover! Didn’t you see

the bound it gave?

And she once more burst into uproarious mirth.

But though he made an effort to the contrary, tears appeared in the

young man’s eyes, and with that she flung her arms tenderly round

his neck.

“How silly you are! You know I love you all the same. If one never

broke anything the tradesmen would never sell anything. All that

sort of thing’s made to be broken. Now look at this fan; it’s only

held together with glue!”

She had snatched up a fan and was dragging at the blades so that the

silk was torn in two. This seemed to excite her, and in order to

show that she scorned the other presents, the moment she had ruined

his she treated herself to a general massacre, rapping each

successive object and proving clearly that not one was solid in that

she had broken them all. There was a lurid glow in her vacant eyes,

and her lips, slightly drawn back, displayed her white teeth. Soon,

when everything was in fragments, she laughed cheerily again and

with flushed cheeks beat on the table with the flat of her hands,

lisping like a naughty little girl:

“All over! Got no more! Got no more!”

Then Philippe was overcome by the same mad excitement, and, pushing

her down, he merrily kissed her bosom. She abandoned herself to him

and clung to his shoulders

Comments (0)