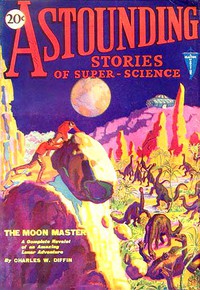

Two Thousand Miles Below by Charles Willard Diffin (whitelam books TXT) 📗

- Author: Charles Willard Diffin

Book online «Two Thousand Miles Below by Charles Willard Diffin (whitelam books TXT) 📗». Author Charles Willard Diffin

They were through with their work, these great yellow-skinned naked men—or mole-men. Six of them—Smithy counted them slowly before he took aim—and two were armed with flame-throwers.

Smithy rested his arm across the little hummock of gritty ash that had sheltered him and sent six flashes of flame through the night toward the cluster of bodies.

e made no attempt to aim at each individual—the shapes were too shadowy for that. And he had no knowledge of what other weapons they might have. One thing was sure: he must take no chances on facing the red ones single-handed. He rammed his empty pistol back into its holster as he turned and ran—ran with every ounce of energy he possessed to drive his flying feet across the crater floor, out through the cleft in the rocks and down the steep mountainside.

He was stunned by the suddenness of the catastrophe that had overtaken them. The horror of Dean Rawson's going; the fearful reality of those "devils from hell" that old Riley had seen—it was all too staggering, too numbing, for easy acceptance. Time was required for the truth to sink in; and through the balance of the night Smithy had plenty of time to think.

He dared not go back to the camp where ripping flashes of green light told him the enemy was at work. And then, even had it been possible to creep up on them in the darkness, that one chance vanished as the desert about the camp sprang into view. One after another the buildings burst into flame, and Smithy was thankful for the concealment of the vast, empty desert.

he embers were still glowing when he dared go near. This enemy, it seemed, worked only at night, and Smithy waited only for the sun to show above distant purple ranges. It had been their enemy once, that fiercely hot sun; they had fought against the heat—but never had the sun wrought such destruction as this.

Smithy looked from haggard, hopeless eyes upon the wreckage of Rawson's camp. For the men who had worked there, this had meant only a job; to Smithy it had been a fight against the desert which had defeated him once. But to Rawson it meant the fruit of years of effort, the goal of his dreams brought almost within his reach.

Smithy looked at the smoldering heaps of gray where an idle wind puffed playfully at fluffy ash or fanned a bed of coals to flame. Twisted steel of the wrecked derrick was still further distorted; the enemy had ripped it to pieces with his stabbing flames. Even the unused materials, the steel and cement that had been neatly stacked for future use—the flames had been turned on it all.

And Smithy, though his voice broke almost boyishly from his repressed emotion, spoke aloud in solemn promise:

"It's too late to help you, Dean. I'll go back to town, report to the men who were back of you, and then.... They're going to pay, Dean! Whoever—whatever—they are, they're going to pay!"

He turned away toward the mountains and the ribbon of road that wound off toward the canyon. Then, at some recollection, he swung back.

"The cable's still down—he would have wanted it left all shipshape," he whispered.

Where the derrick had stood was the mouth of the twenty-inch casing. The cable that ran from it was entangled with the wreckage of the derrick, but it had not been cut. Smithy set doggedly to work.

little gin-pole and light tackle allowed him to erect a heavier tripod of steel beams; it hoisted the big sheave block into place, and gave Smithy's two hands the strength of twenty to rig a temporary hoist. The juice was still on the main feed line, and the hoisting motors hummed at his touch. The ten miles of cable wound slowly onto the drums.

"It's nonsense, I suppose," he told himself silently. But something drove him to do this last thing—to leave it all as Rawson would have had it.

The long bailer came out at last; there was just room to hoist it clear and let it drop back upon the drilling floor. A glint of gold flashed in the sunlight as Smithy let the long metal tube down, and he broke into voluble cursing at sight of the bit of metal that was caught near the bailer's top.

The gold had started it all! That first finding of the gold on the big drill had begun it.... He crossed swiftly to the gleaming thing that seemed somehow to symbolize his loss.

He stooped to reach for it, intending to throw it as far as he could. Instead he stood in an awkward stooping attitude—stood so while the long uncounted minutes passed....

His eyes that stared and stared in disbelief seemed suddenly to have turned traitor. They were telling him that they saw a ring—a cameo—jammed solidly into the shackle at the bailer's end. And that ring, when last he had seen it, had been on Dean Rawson's hand! Dean had caught it; he had hooked it over a lever in this very place—and now, from ten miles down inside the solid earth, it had returned. It meant—it meant....

But the stocky, broad-shouldered youngster known as Smithy dared not think what it meant. Nor had he time to follow the thought; he was too busily engaged in running at suicidal speed across the hot sand toward barren mountains where a ribbon of road showed through quivering air.

CHAPTER VIII The Darknessarkness; and red fires that seemed whirling about him as his body twisted in air. To Dean Rawson, plunging down into the volcano's maw, each second was an eternity, for, in each single instant, he was expecting crashing death.

Then he knew that long arms were wrapped about him, holding him, supporting him, checking his downward plunge ... and at last the glassy walls, where each bulbous irregularity shone red with reflected light, moved slowly past. And, after more eons of time, a rocky floor rose slowly to meet him.

His body crashed gently; he was sprawled face downward on stone that was smooth and cold. The restraining arms no longer touched him.

He lay motionless for some time, his mind as stunned and uncomprehending as if he had truly crashed to death upon that rocky floor. Then, at last, he forced his reluctant nerves and muscles to turn his body till he lay face upward.

Darkness wrapped him as if it were the soft swathing of some black cocoon. The world about him was at first a place of utter night-time blackness; and then, far above him, there shone a single star ... until that feeble candle-gleam, too, was snuffed out.

A hand was gripping his shoulder; it seemed urging him to arise. He felt each separate finger—long, slender, like bands of steel. The nail at each finger-end was more nearly a claw, the whole hand a thin, clutching thing like the foot of some giant ape. And, even as he shrank involuntarily from that touch, Rawson wondered how the creature could reach out and grip him so surely in the dark. But he came to his feet in response to that urging hand.

The night was suddenly sibilant with eery, whistling voices. They came from all sides at once; they threw themselves back and forth in endless echoes. To Rawson it was only a confused medley of conflicting sounds in which no one voice was clear. But the creature that held him must have understood, for he heard him reply in a sharp, piercing tone, half whistle, half shriek.

hat had happened? Where was he? What was this thing that pushed him, stumbling, along through the dark? With all his tumultuous questioning he knew only one thing definitely: that it would be of no use to struggle. He was as helpless as any trapped animal.

He was inside the earth, of course; he had fallen he had no least idea how far; and, in some strange manner, this long-armed thing had supported him and eased him gently down. But what it meant or what lay ahead were matters too obscure for him to try to see clearly.

He held his hands protectingly before him while the talons gripping into his shoulder hurried him along. He stumbled awkwardly as his foot struck an obstruction. He would have fallen but for the grip that held him erect.

For that creature, whatever it was, the darkness held no uncertainty. He moved swiftly. His shrill shriek and the jerk of his arm both gave evidence of his astonishment that his captive should walk so blunderingly.

Then it seemed that he must have comprehended Rawson's blindness. A green line of light passed close behind Dean's head. It was cold—there was no radiant warmth—but, when it struck the face of a wall of stone some twenty feet away, the solid rock turned instantly to a mass of glowing yellow-red.

The cold green ray swung back and forth, leaving a path of radiant rock behind it wherever it touched. And the rock was hot! Once the green light held more than an instant in one place, and the rock softened at its touch, then splashed and trickled down to make a fiery pool.

bruptly Rawson was able to see his surroundings. Also, he knew the source of the red glow that had seemed like volcanic fires. There had been others like his captor; they had been down below, and had played their flames upon the rocks deep in the volcano. It was thus that they made light.

With equal suddenness, and with terrible clearness, Dean found the answer to one of his questions. He wrenched himself about to stare behind him at the creature that held him in its grip. And, for the first time, the wild experience became something more than an unbelievable nightmare; in that one horrifying instant he knew it was true.

Only a few minutes before, he had been walking across the cindery sand of the crater top, walking under the stars and the dark desert sky—Dean Rawson, mining engineer, in a sane, believable world. And now...!

He squinted his eyes in the dim light to see more plainly the beastly figure, more horrible for being so nearly human. He had seen them briefly up above; the closer view of this one specimen of a strange race was no more pleasing. For now he saw clearly the cruelty in the face. It was there unmistakably, even though the face itself, under less threatening circumstances, might have been a ludicrous caricature of a man's.

Red and nearly naked, the creature stood upright, straps of metal about its body. It was about Rawson's height; its round, staring eyes were about level with his own, and each eye was centered in a circular disk of whitish skin. The light went dim for a moment, and Dean, staring in his turn, saw those other huge eyes enlarge, the white covering of each drawing back like an expanding iris.

Some vague understanding came to him of the beast's ability to see in the dark. They used these red-hot stones for illumination, but this thing had seemed to see clearly even when the stones had ceased to glow. And again, though indistinctly, Dean knew that those eyes might be sensitive to infra-red radiations—they might see plainly by the dark light that continued to flood these rocky chambers, though, to him, the rocks had gone lightless and black.

ven as the quick thoughts flashed through his mind, he was thinking other thoughts, recording other observations.

The rest of the face was red like the body; the head was sharply pointed, and crowned with a mass of thin, clinging locks of hair. The mouth, a round, lipless orifice, contracted or dilated at will; from it came whistling words.

Out of the darkness, giant things were leaping. They clutched at Rawson, while the first captor released his hold and drew back. Taller, these newcomers were, bigger, and different.

In the red light from the hot rocks Dean saw their faces, in which were owl eyes like those of the first one, but yellow, expressionless and stupid. Their great bodies were yellow: their outstretched hands were webbed.

For one instant, as Rawson's hand touched his pistol in its holster, a surge of fighting rage swept through him. His whole being

Comments (0)