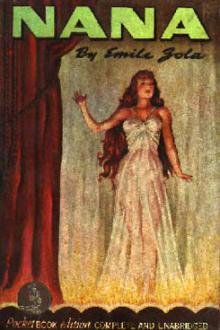

Nana - Émile Zola (good books to read for young adults txt) 📗

- Author: Émile Zola

- Performer: -

Book online «Nana - Émile Zola (good books to read for young adults txt) 📗». Author Émile Zola

at you. Men do not fight for Nana; it would be ridiculous.”

The count grew very pale and made a violent gesture.

“Then I shall slap his face in the open street.”

For an hour Labordette had to argue with him. A blow would make the

affair odious; that evening everyone would know the real reason of

the meeting; it would be in all the papers. And Labordette always

finished with the same expression:

“It is impossible; it would be ridiculous.”

Each time Muffat heard these words they seemed sharp and keen as a

stab. He could not even fight for the woman he loved; people would

have burst out laughing. Never before had he felt more bitterly the

misery of his love, the contrast between his heavy heart and the

absurdity of this life of pleasure in which it was now lost. This

was his last rebellion; he allowed Labordette to convince him, and

he was present afterward at the procession of his friends, who lived

there as if at home.

Nana in a few months finished them up greedily, one after the other.

The growing needs entailed by her luxurious way of life only added

fuel to her desires, and she finished a man up at one mouthful.

First she had Foucarmont, who did not last a fortnight. He was

thinking of leaving the navy, having saved about thirty thousand

francs in his ten years of service, which he wished to invest in the

United States. His instincts, which were prudential, even miserly,

were conquered; he gave her everything, even his signature to notes

of hand, which pledged his future. When Nana had done with him he

was penniless. But then she proved very kind; she advised him to

return to his ship. What was the good of getting angry? Since he

had no money their relations were no longer possible. He ought to

understand that and to be reasonable. A ruined man fell from her

hands like a ripe fruit, to rot on the ground by himself.

Then Nana took up with Steiner without disgust but without love.

She called him a dirty Jew; she seemed to be paying back an old

grudge, of which she had no distinct recollection. He was fat; he

was stupid, and she got him down and took two bites at a time in

order the quicker to do for this Prussian. As for him, he had

thrown Simonne over. His Bosphorous scheme was getting shaky, and

Nana hastened the downfall by wild expenses. For a month he

struggled on, doing miracles of finance. He filled Europe with

posters, advertisements and prospectuses of a colossal scheme and

obtained money from the most distant climes. All these savings, the

pounds of speculators and the pence of the poor, were swallowed up

in the Avenue de Villiers. Again he was partner in an ironworks in

Alsace, where in a small provincial town workmen, blackened with

coal dust and soaked with sweat, day and night strained their sinews

and heard their bones crack to satisfy Nana’s pleasures. Like a

huge fire she devoured all the fruits of stock-exchange swindling

and the profits of labor. This time she did for Steiner; she

brought him to the ground, sucked him dry to the core, left him so

cleaned out that he was unable to invent a new roguery. When his

bank failed he stammered and trembled at the idea of prosecution.

His bankruptcy had just been published, and the simple mention of

money flurried him and threw him into a childish embarrassment. And

this was he who had played with millions. One evening at Nana’s he

began to cry and asked her for a loan of a hundred francs wherewith

to pay his maidservant. And Nana, much affected and amused at the

end of this terrible old man who had squeezed Paris for twenty

years, brought it to him and said:

“I say, I’m giving it you because it seems so funny! But listen to

me, my boy, you are too old for me to keep. You must find something

else to do.”

Then Nana started on La Faloise at once. He had for some time been

longing for the honor of being ruined by her in order to put the

finishing stroke on his smartness. He needed a woman to launch him

properly; it was the one thing still lacking. In two months all

Paris would be talking of him, and he would see his name in the

papers. Six weeks were enough. His inheritance was in landed

estate, houses, fields, woods and farms. He had to sell all, one

after the other, as quickly as he could. At every mouthful Nana

swallowed an acre. The foliage trembling in the sunshine, the wide

fields of ripe grain, the vineyards so golden in September, the tall

grass in which the cows stood knee-deep, all passed through her

hands as if engulfed by an abyss. Even fishing rights, a stone

quarry and three mills disappeared. Nana passed over them like an

invading army or one of those swarms of locusts whose flight scours

a whole province. The ground was burned up where her little foot

had rested. Farm by farm, field by field, she ate up the man’s

patrimony very prettily and quite inattentively, just as she would

have eaten a box of sweetmeats flung into her lap between

mealtimes. There was no harm in it all; they were only sweets! But

at last one evening there only remained a single little wood. She

swallowed it up disdainfully, as it was hardly worth the trouble

opening one’s mouth for. La Faloise laughed idiotically and sucked

the top of his stick. His debts were crushing him; he was not worth

a hundred francs a year, and he saw that he would be compelled to go

back into the country and live with his maniacal uncle. But that

did not matter; he had achieved smartness; the Figaro had printed

his name twice. And with his meager neck sticking up between the

turndown points of his collar and his figure squeezed into all too

short a coat, he would swagger about, uttering his parrotlike

exclamations and affecting a solemn listlessness suggestive of an

emotionless marionette. He so annoyed Nana that she ended by

beating him.

Meanwhile Fauchery had returned, his cousin having brought him.

Poor Fauchery had now set up housekeeping. After having thrown over

the countess he had fallen into Rose’s hands, and she treated him as

a lawful wife would have done. Mignon was simply Madame’s major-domo. Installed as master of the house, the journalist lied to Rose

and took all sorts of precautions when he deceived her. He was as

scrupulous as a good husband, for he really wanted to settle down at

last. Nana’s triumph consisted in possessing and in ruining a

newspaper that he had started with a friend’s capital. She did not

proclaim her triumph; on the contrary, she delighted in treating him

as a man who had to be circumspect, and when she spoke of Rose it

was as “poor Rose.” The newspaper kept her in flowers for two

months. She took all the provincial subscriptions; in fact, she

took everything, from the column of news and gossip down to the

dramatic notes. Then the editorial staff having been turned topsy-turvy and the management completely disorganized, she satisfied a

fanciful caprice and had a winter garden constructed in a corner of

her house: that carried off all the type. But then it was no joke

after all! When in his delight at the whole business Mignon came to

see if he could not saddle Fauchery on her altogether, she asked him

if he took her for a fool. A penniless fellow living by his

articles and his plays—not if she knew it! That sort of

foolishness might be all very well for a clever woman like her poor,

dear Rose! She grew distrustful: she feared some treachery on

Mignon’s part, for he was quite capable of preaching to his wife,

and so she gave Fauchery his CONGE as he now only paid her in fame.

But she always recollected him kindly. They had both enjoyed

themselves so much at the expense of that fool of a La Faloise!

They would never have thought of seeing each other again if the

delight of fooling such a perfect idiot had not egged them on! It

seemed an awfully good joke to kiss each other under his very nose.

They cut a regular dash with his coin; they would send him off full

speed to the other end of Paris in order to be alone and then when

he came back, they would crack jokes and make allusions he could not

understand. One day, urged by the journalist, she bet that she

would smack his face, and that she did the very same evening and

went on to harder blows, for she thought it a good joke and was glad

of the opportunity of showing how cowardly men were. She called him

her “slapjack” and would tell him to come and have his smack! The

smacks made her hands red, for as yet she was not up to the trick.

La Faloise laughed in his idiotic, languid way, though his eyes were

full of tears. He was delighted at such familiarity; he thought it

simply stunning.

One night when he had received sundry cuffs and was greatly excited:

“Now, d’you know,” he said, “you ought to marry me. We should be as

jolly as grigs together, eh?”

This was no empty suggestion. Seized with a desire to astonish

Paris, he had been slyly projecting this marriage. “Nana’s husband!

Wouldn’t that sound smart, eh?” Rather a stunning apotheosis that!

But Nana gave him a fine snubbing.

“Me marry you! Lovely! If such an idea had been tormenting me I

should have found a husband a long time ago! And he’d have been a

man worth twenty of you, my pippin! I’ve had a heap of proposals.

Why, look here, just reckon ‘em up with me: Philippe, Georges,

Foucarmont, Steiner—that makes four, without counting the others

you don’t know. It’s a chorus they all sing. I can’t be nice, but

they forthwith begin yelling, ‘Will you marry me? Will you marry

me?’”

She lashed herself up and then burst out in fine indignation:

“Oh dear, no! I don’t want to! D’you think I’m built that way?

Just look at me a bit! Why, I shouldn’t be Nana any longer if I

fastened a man on behind! And, besides, it’s too foul!”

And she spat and hiccuped with disgust, as though she had seen all

the dirt in the world spread out beneath her.

One evening La Faloise vanished, and a week later it became known

that he was in the country with an uncle whose mania was botany. He

was pasting his specimens for him and stood a chance of marrying a

very plain, pious cousin. Nana shed no tears for him. She simply

said to the count:

“Eh, little rough, another rival less! You’re chortling today. But

he was becoming serious! He wanted to marry me.”

He waxed pale, and she flung her arms round his neck and hung there,

laughing, while she emphasized every little cruel speech with a

caress.

“You can’t marry Nana! Isn’t that what’s fetching you, eh? When

they’re all bothering me with their marriages you’re raging in your

corner. It isn’t possible; you must wait till your wife kicks the

bucket. Oh, if she were only to do that, how you’d come rushing

round! How you’d fling yourself on the ground and make your offer

with all the grand accompaniments—sighs and tears and vows!

Wouldn’t it be nice, darling, eh?”

Her voice

Comments (0)