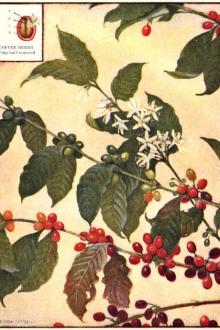

All About Coffee - William H. Ukers (best novel books to read .TXT) 📗

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Book online «All About Coffee - William H. Ukers (best novel books to read .TXT) 📗». Author William H. Ukers

The chinaware, or glazed earthenware pot, sometimes called the French drip pot, with a chinaware or earthenware sieve container for the grounds at the top through which the water is poured, being free of all metal, is inviting in purity and in hygienic merit. Together with the filter bag, it is subject to the above remarks on dimensions. A chinaware sieve cannot be made as fine as a metal sieve and cannot of course hold very fine granulation as can cotton cloth. More coffee for a given strength is, therefore, required. The upper container should be wide enough, for a given quantity of coffee, as to allow an unretarded flow, and the more openings the strainer contains the better.

In any drip, filtration or percolating method the stirring of the grounds causes an over-contact of water and coffee and results in an overdrawn liquor of injured flavor. If the water does not pass through the grounds readily, the fault is as above indicated and cannot be corrected by stirring or agitation. Many complaints of bitter taste are traced to this error in the use of the filtration method.

It is not necessary to pour on the water in driblets. The water may be poured slowly, but the grounds should be kept well covered. The weight of the water helps the flow downward through the grounds. Care should be taken to keep up the temperature of the water. Set the kettle back on the stove when not pouring. If the water is measured, use a small heated vessel, which fill and empty quickly without allowing the water to cool.

In 1917, The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal made a comparative coffee-brewing test with a regulation coffee pot for boiling, a pumping percolator, a double glass filtration device, a cloth-filter device, and a paper filter device. The cup tests were made by E.M. Frankel, Ph.D.; and William B. Harris, coffee expert, United States Department of Agriculture. The brews were judged for color, flavor (palatability, smoothness), body (richness), and aroma. The test showed that the paper filtration device produced the most superior brew. The cloth-filter, glass-filter, percolator, and boiling pot followed in the order named.

At the 1917 convention of the National Coffee Roasters Association, John E. King, of Detroit, announced that laboratory research which he had had conducted for him showed that the finer the grind, the greater the loss of aroma, and so he had selected a grind containing ninety percent of very fine coffee and ten percent of a coarser nature, which seemed to retain the aroma. He subsequently secured a United States patent for this grind. Mr. King announced also at this meeting that his investigations showed there was more than a strong likelihood that the much-discussed caffetannic acid did not exist in coffee—that it most probably was a mixture of chlorogenic and and coffalic acids.

The World War operated to interfere with the coffee roasters' plans for a research bureau; and in the meantime the Brazil planters, in 1919, started their million-dollar advertising campaign in the United States, co-operating with a joint committee representing the green and roasted coffee interests. In the following year (June, 1920), this committee arranged with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to start scientific research work on coffee, the literature of the roasters' Better Coffee Making Committee being turned over to it; and the Institute began to "test the results of the committee's work by purely analytical methods."

The first report on the research work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was made by Professor S.C. Prescott to the Joint Coffee Trade Publicity Committee in April, 1921. The committee gave out a statement saying that Prof. Prescott's report stated that "caffein, the most characteristic principle of coffee, is, in the moderate quantities consumed by the average coffee drinker, a safe stimulant without harmful after-effects."

There was no publication of experimental results; but the announced findings were, in the main, a confirmation of the results of previous workers, particularly of Hollingworth, with whose statement, that "caffein, when taken with food in moderate amount is not in the least deleterious," the report was quoted as being in entire agreement.

At the annual convention of the National Coffee Roasters Association, November 2, 1921, Professor Prescott made a further report, in which he stated that investigations on coffee brewing had disclosed that coffee made with water between 185° and 200° was to be preferred to coffee made with the water at actual boiling temperature (212°), that the chemical action was far less vigorous, and that the resulting infusion retained all the fine flavors and was freer from certain bitter or astringent flavors than that made at the higher temperature. Professor Prescott announced also that the best materials for coffee-making utensils were glass (including agate-ware, vitrified ware, porcelain, etc.), aluminum, nickel or silver plate, copper, and tin plate, in the order named[381].

The Joint Coffee Trade Publicity Committee's booklet on Coffee and Coffee Making, issued in 1921, was very guarded in its observations on grinding and brewing. It avoided all controversial points, but it did go so far as to say on the general subject of brewing:

Chemists have analyzed the coffee bean and told us that the only part of it which should go into our coffee cups for drinking is an aromatic oil. This aromatic element is extracted most efficiently only by fresh boiling water. The practice of soaking the grounds in cold water, therefore, is to be condemned. It is a mistake also to let the water and the grounds boil together after the real coffee flavor is once extracted. This extraction takes place very quickly, especially when the coffee is ground fine. The coarser the granulation the longer it is necessary to let the grounds remain in contact with the boiling water. Remember that flavor, the only flavor worth having, is extracted by the short contact of boiling water and coffee grounds and that after this flavor is extracted, the coffee grounds become valueless dregs.

The report contained also the following helpful generalities on coffee service and the various methods of brewing in more or less common use in the United States in 1921:

Although the above rules are absolutely fundamental to good Coffee Making, their importance is so little appreciated that in some households the lifeless grounds from the breakfast Coffee are left in the pot and resteeped for the next meal, with the addition of a small quantity of fresh coffee. Used coffee grounds are of no more value in coffee making than ashes are in kindling a fire.

After the coffee is brewed the true coffee flavor, now extracted from the bean, should be guarded carefully. When the brewed liquid is left on the fire or overheated this flavor is cooked away and the whole character of the beverage is changed. It is just as fatal to let the brew grow cold. If possible, coffee should be served as soon as it is made. If service is delayed, it should be kept hot but not overheated. For this purpose careful cooks prefer a double boiler over a slow flre. The cups should be warmed beforehand, and the same is true of a serving pot, if one is used. Brewed coffee, once injured by cooling, cannot be restored by reheating.

Unsatisfactory results in coffee brewing frequently can be traced to a lack of care in keeping utensils clean. The fact that the coffee pot is used only for coffee making is no excuse for setting it away with a hasty rinse. Coffee making utensils should be cleansed after each using with scrupulous care. If a percolator is used pay special attention to the small tube through which the hot water rises to spray over the grounds. This should be scrubbed with the wire-handled brush that comes for the purpose.

In cleansing drip or filter bags use cool water. Hot water "cooks in" the coffee stains. After the bag is rinsed keep it submerged in cool water until time to use it again. Never let it dry. This treatment protects the cloth from the germs in the air which cause souring. New filter bags should be washed before using to remove the starch or sizing.

Drip (or Filter) Coffee. The principle behind this method is the quick contact of water at full boiling point with coffee ground as fine as it is practical to use it. The filtering medium may be of cloth or paper, or perforated chinaware or metal. The fineness of the grind should be regulated by the nature of the filtering medium, the grains being large enough not to slip through the perforations.

The amount of ground coffee to use may vary from a heaping teaspoonful to a rounded tablespoonful for each cup of coffee desired, depending upon the granulation, the kind of apparatus used and individual taste. A general rule is the finer the grind the smaller the amount of dry coffee required.

The most satisfactory grind for a cloth drip bag has the consistency of powdered sugar and shows a slight grit when rubbed between thumb and finger. Unbleached muslin makes the best bag for this granulation. For dripping coffee reduced to a powder, as fine as flour or confectioner's sugar, use a bag of canton flannel with the fuzzy side in. Powdered coffee, however, requires careful manipulation and cannot be recommended for everyday household use.

Put the ground coffee in the bag or sieve. Bring fresh water to a full boil and pour it through the coffee at a steady, gradual rate of flow. If a cloth drip bag is used, with a very finely ground coffee, one pouring should be enough. No special pot or device is necessary. The liquid coffee may be dripped into any handy vessel or directly into the cups. Dripping into the coffee cups, however, is not to be recommended unless the dripper is moved from cup to cup so that no one cup will get more than its share of the first flow, which is the strongest and best.

The brew is complete when it drips from the grounds, and further cooking or "heating up" injures the quality. Therefore, since it is not necessary to put the brew over the fire, it is possible to make use of the hygienic advantages of a glassware, porcelain or earthenware serving pot.

Boiled (or Steeped) Coffee. For boiling (or steeping) use a medium grind. The recipe is a rounded tablespoonful for each cup of coffee desired or—as some cooks prefer to remember it—a tablespoonful for each cup and "one for the pot." Put the dry coffee in the pot and pour over it fresh water briskly boiling. Steep for five minutes or longer, according to taste, over a low fire. Settle with a dash of cold water or strain through muslin or cheesecloth and serve at once.

Percolated Coffee. Use a rounded tablespoonful of medium fine ground coffee to each cupful of water. The water may be poured into the percolator cold or at the boiling point. In the latter case, percolation begins at once. Let the water percolate over the grounds for five or ten minutes depending upon the intensity of the heat and the flavor desired.

In response to a request by the author, Charles W. Trigg has contributed the following discussion of coffee making:

Various Aspects of Scientific Coffee Brewing

Before converting it into the beverage form, coffee must be carefully selected and blended, and skillfully roasted, in order thus far to assure obtaining a maximum efficiency of results. No matter how accurately all this be done, improper brewing of the roasted bean will nullify the previous efforts and spoil the drink; for roasted coffee is a delicate material, very susceptible to deterioration and of doubtful worth as the source of a beverage unless properly handled.

Comments (0)