Castles and Cave Dwellings of Europe - Sabine Baring-Gould (books to read to improve english TXT) 📗

- Author: Sabine Baring-Gould

Book online «Castles and Cave Dwellings of Europe - Sabine Baring-Gould (books to read to improve english TXT) 📗». Author Sabine Baring-Gould

northern transept that was glued to the rock. The oratory of S. Martin was levelled to the rock on which it stood.

But the fact of the transfer of the monastery to the flat land below the cliff had this effect, that the old caves, the original cradle of Marmoutier, were neglected and forgotten. They were overgrown by brambles, crumbled away, and none visited them.

In 1859 the oratory in which S. Martin had prayed was restored or rather rebuilt from its foundations.

One night when Martin was engaged therein in reading the Scriptures, the door was burst open and in broke a party of masqueraders. They had disguised themselves as Jupiter, Minerva, and Mercury, and some damsel devoid of modesty presented herself before the startled modesty of the bishop without disguise of any sort, as Venus rising from the foam of the sea. Some were dressed as Wood Druses very much like the devils of popular fancy. Mercury was a sharp, shrewd wag, and bothered the saint greatly, as he admitted to Sulpicius, his biographer, but Jupiter was a "stupid sot." At the rebuke of Martin the whole gang good-humouredly withdrew.

I was in this cell on Mid Lent Sunday, when hearing a noise outside, I looked forth and saw a party of masqueraders frolic and frisk past on their way to a tavern where was to be a costume ball. So goes the world. Some fifteen hundred and thirty years ago the Gospel was being preached in Tours, as it is now, men and women were striving to follow its precepts as now, and tomfoolery was rampant in Tours fifteen hundred and thirty years ago as it is now.

And now, as to the remains in the rock of the primitive Marmoutier. The grottoes of S. Gatianus and of the disciples of S. Martin have been cleared out. There is a little arcade of three round-headed unadorned arches cut in the cliff that served as a cloister, and there is the old baptistry where Martin admitted his converts into the Christian Church, sunk in the rock for adult and complete submersion, and the niches in the wall for the sacred oils. Adjoining is the cave in which the neophyte unclothed and afterwards reclothed himself. There are graves sunk in the rock, where some of his disciples were laid, and there is the chapel partly in the rock and partly rebuilt, dedicated later by Gregory of Tours to the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, but of which in after times a different story was told--namely that seven brothers who had been devoted disciples of Martin prayed him when he was dying that they might speedily follow, and on the anniversary of his death they all seven fell asleep.

There is another cave that escaped destruction at the Revolution, though opening out of the transept of the church. It is that of the Penitence of Brice.

Brice had been adopted as a child by Martin, and brought up by him to be a monk. But Brice had no liking for the religious life, and was very disrespectful to his master. One day a sick man came to see Martin and asked of Brice where the saint was. "The fool is yonder," answered he, "staring at the sky like an idiot."

One day Martin rebuked Brice for buying horses and slaves at a high price, and even providing himself with beautiful young girls. Brice was furious, and said. "I am a better Christian than you. I have had an ecclesiastical education from my youth, and you were bred up amidst the license of a camp."

On the death of S. Martin, the people of Tours, tired of having a saint at their head, with proverbial fickleness chose Brice as his successor because rich--he was said to have been the son of the Count of Nevers-- and because he was anything but a saint. As bishop he showed little improvement, and gave great scandal. Lazarus, Bishop of Aix, accused him before several councils. At last a gross outrage on morals was attributed to him, and caused his flight. A nun gave birth to a child, and confessed that she had been seduced by the bishop. Brice either ran away from Tours or was deposed. A priest named Justinian was elected in his room. On the death of Justinian, Armentius succeeded him. Brice remained in exile till the death of Armentius, and then ventured back to Tours to reclaim his episcopal throne. He was allowed to reascend it, and he occupied it for seven years; and the cave in which he did penance for his frailties and the scandal he had caused is intact to this day. He died, after having been nominally bishop for forty-seven years, the greater portion of which time he had spent in exile. The Church of Rome is certainly very charitably disposed in numbering him among the saints. Why he should be regarded as the patron of wool- combers one cannot see, [Footnote: The following prayer is recommended by the Archbishop of Tours to the faithful for use. "Nous vous supplions, Seigneur, par l'intercession de S. Brice, Eveque et Confesseur, de conserver votre peuple qui se confie en votre amour; afin que, par les vertues de notre Saint Pontife, nous meritions de partager avec lui les joies celestes." The virtues of Brice!] but as such he enjoyed some popularity.

There is yet another cave in the Marmoutier rocks that may be mentioned; it is that of S. Leobard. Leobard was a saint of the sixth century, a native of Auvergne, who, coming to pray at the tomb of S. Martin, resolved on spending the rest of his days in one of the cells of Martin's monastery in the rocks. He settled into an untenanted cave, which he enlarged, and lived in it for twenty-two years. At the extremity he dug a deep pit in which he desired to be buried standing with his face to the East, thus to await the coming of the Lord. But although his desire was fulfilled, the monks of Marmoutier would not let his body rest there, but hauled it up, that it might become an object of devotion to the faithful.

The Abbey of Brantome on the Dronne (Dep. Dordogne) was originally, like Marmoutier, a cavern monastery, and like those of Marmoutier, the monks waxing fat, they kicked and abandoned the grottoes for a stately structural monastery. The beautiful Romanesque tower of the church stands on top of a rock that is honeycombed with their cells. The church, consisting of nave only, is of marvellous beauty, early pointed, and built on a curve, as there was but little space to spare between the river and the cliffs. Unhappily church and cloister were delivered over to be "restored" by that arch-wrecker, Abbadie, who has done such incalculable mischief in Perigord and the Angoumois, and his hoof-mark is visible here. The monks, not content with a sumptuous Gothic abbey, pulled it down and built one in the baroque style, and had but just completed it when the Revolution broke out "and the flood came and swept them all away." In the court behind this modern structure is to be seen the cliff perforated with caves; it has, however, been cut back to the detriment of these, so that we have them shorn of their faces. Nevertheless they are interesting. The old monolithic chapel of the monastery remains, turned into a pigeonry, and with the steps left that gave access to the pulpit, and two pieces of sculpture on a very large scale, cut out of the living rock. One represents the Crucifixion with SS. Mary and John; the other has been variously explained as the Last Judgment or the Triumph of Death. It perhaps represents the Triumph of Christ over Death. His figure and the kneeling figures of His Mother and the Beloved Disciple were, however, never completed, and remain in the rough.

Beneath the figure of Christ is Death, figured by a head surmounted by a crown of bones, and a crest representing a spectre armed with a club. On each side is an angel blowing a trumpet. Below are ranged a dozen heads of popes, bishops, princes, knights, and ladies, in boxes to represent graves.

Sculpture in the cave monastery of Brantome. The figure of Christ was never completed. Below is a head crowned with bones, for Death, with Time as crest. Below, in boxes, are the dead, of various degrees.]

In the front of this huge piece of sculpture are trestles planted in the ground to support planks to serve as tables when the Brantomois desire to have a banquet and a dance.

The sculpture above described is not earlier than the sixteenth century. A few paces from it, in the same line and almost under the tower, is another grotto called _La Babayou_--that is to say "of the statue," and it probably at one time enshrined an image of a saint. On the left of the subterranean church is the fountain of the little Cut-throat already mentioned. S. Sicarius, whose relics were the great "draw" to Brantome in the Middle Ages, was supposed to have been one of the Innocents slain by Herod; and the relics were also supposed to have been given to the abbey by Charlemagne. As there was no historic evidence that Charles the Great ever had a set of little bones passed off on him as those of the Innocent, or that he ever made a present to the abbey of a relic, it will be seen that a good deal of supposition goes to the story. As I have said before, how it was that the child of a Hebrew mother acquired a Latin name, and that one so peculiar, we are not informed.

Outside the town gate are other large excavations that are supposed to have formed a temple of Mithras, but this is mere conjecture. The largest is now employed as a _Tir_--a shooting gallery. That there were buildings connected with it is seen by the holes in the rock to receive rafters.

S. Maximus, Bishop of Riez, who died in 460, was born at Chateau Redon, near Digne, and he entered the monastic life on the isle of Lerins, under S. Honoratus, and when that saint was raised in 426 to the episcopal throne of Arles, Maximus succeeded him as Abbot of Lerins. But this monastery was becoming crowded, and Maximus pined for the solitary life, so one day he took a boat, crossed to the mainland, and plunged into the wild country about the river Verdon, that has sawn for itself a chasm through the limestone; where it debouches, he planted himself at a place since called Moustier-Ste-Marie. The lips of the crevasse are linked by a chain, with a gilt star hanging in the midst, little under 690 feet above the bed of the torrent. No one knows when this star was hung there, but it is supposed to have been an _ex voto_ of a chevalier, de Blac. Within the ravine, reached by a narrow goat-path, were caves in the cliffs, and into one of these Maximus retired in 434 and was speedily followed by other solitaries. The caves are still there, the faces walled up, but as at Liguge, and as at Marmoutier, and as at Brantome, so was it here. As the monastery grew rich, the solitaries crawled out of their holes into which the sun never shone, and erected their residence at the opening of the ravine. A chapel remains, founded by Charlemagne, but rebuilt in the fourteenth or fifteenth century, reached by a stair protected by a parapet.

Moustier was famous at the close of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth century for its faience, with elegant designs and good colouring. Specimens are

But the fact of the transfer of the monastery to the flat land below the cliff had this effect, that the old caves, the original cradle of Marmoutier, were neglected and forgotten. They were overgrown by brambles, crumbled away, and none visited them.

In 1859 the oratory in which S. Martin had prayed was restored or rather rebuilt from its foundations.

One night when Martin was engaged therein in reading the Scriptures, the door was burst open and in broke a party of masqueraders. They had disguised themselves as Jupiter, Minerva, and Mercury, and some damsel devoid of modesty presented herself before the startled modesty of the bishop without disguise of any sort, as Venus rising from the foam of the sea. Some were dressed as Wood Druses very much like the devils of popular fancy. Mercury was a sharp, shrewd wag, and bothered the saint greatly, as he admitted to Sulpicius, his biographer, but Jupiter was a "stupid sot." At the rebuke of Martin the whole gang good-humouredly withdrew.

I was in this cell on Mid Lent Sunday, when hearing a noise outside, I looked forth and saw a party of masqueraders frolic and frisk past on their way to a tavern where was to be a costume ball. So goes the world. Some fifteen hundred and thirty years ago the Gospel was being preached in Tours, as it is now, men and women were striving to follow its precepts as now, and tomfoolery was rampant in Tours fifteen hundred and thirty years ago as it is now.

And now, as to the remains in the rock of the primitive Marmoutier. The grottoes of S. Gatianus and of the disciples of S. Martin have been cleared out. There is a little arcade of three round-headed unadorned arches cut in the cliff that served as a cloister, and there is the old baptistry where Martin admitted his converts into the Christian Church, sunk in the rock for adult and complete submersion, and the niches in the wall for the sacred oils. Adjoining is the cave in which the neophyte unclothed and afterwards reclothed himself. There are graves sunk in the rock, where some of his disciples were laid, and there is the chapel partly in the rock and partly rebuilt, dedicated later by Gregory of Tours to the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, but of which in after times a different story was told--namely that seven brothers who had been devoted disciples of Martin prayed him when he was dying that they might speedily follow, and on the anniversary of his death they all seven fell asleep.

There is another cave that escaped destruction at the Revolution, though opening out of the transept of the church. It is that of the Penitence of Brice.

Brice had been adopted as a child by Martin, and brought up by him to be a monk. But Brice had no liking for the religious life, and was very disrespectful to his master. One day a sick man came to see Martin and asked of Brice where the saint was. "The fool is yonder," answered he, "staring at the sky like an idiot."

One day Martin rebuked Brice for buying horses and slaves at a high price, and even providing himself with beautiful young girls. Brice was furious, and said. "I am a better Christian than you. I have had an ecclesiastical education from my youth, and you were bred up amidst the license of a camp."

On the death of S. Martin, the people of Tours, tired of having a saint at their head, with proverbial fickleness chose Brice as his successor because rich--he was said to have been the son of the Count of Nevers-- and because he was anything but a saint. As bishop he showed little improvement, and gave great scandal. Lazarus, Bishop of Aix, accused him before several councils. At last a gross outrage on morals was attributed to him, and caused his flight. A nun gave birth to a child, and confessed that she had been seduced by the bishop. Brice either ran away from Tours or was deposed. A priest named Justinian was elected in his room. On the death of Justinian, Armentius succeeded him. Brice remained in exile till the death of Armentius, and then ventured back to Tours to reclaim his episcopal throne. He was allowed to reascend it, and he occupied it for seven years; and the cave in which he did penance for his frailties and the scandal he had caused is intact to this day. He died, after having been nominally bishop for forty-seven years, the greater portion of which time he had spent in exile. The Church of Rome is certainly very charitably disposed in numbering him among the saints. Why he should be regarded as the patron of wool- combers one cannot see, [Footnote: The following prayer is recommended by the Archbishop of Tours to the faithful for use. "Nous vous supplions, Seigneur, par l'intercession de S. Brice, Eveque et Confesseur, de conserver votre peuple qui se confie en votre amour; afin que, par les vertues de notre Saint Pontife, nous meritions de partager avec lui les joies celestes." The virtues of Brice!] but as such he enjoyed some popularity.

There is yet another cave in the Marmoutier rocks that may be mentioned; it is that of S. Leobard. Leobard was a saint of the sixth century, a native of Auvergne, who, coming to pray at the tomb of S. Martin, resolved on spending the rest of his days in one of the cells of Martin's monastery in the rocks. He settled into an untenanted cave, which he enlarged, and lived in it for twenty-two years. At the extremity he dug a deep pit in which he desired to be buried standing with his face to the East, thus to await the coming of the Lord. But although his desire was fulfilled, the monks of Marmoutier would not let his body rest there, but hauled it up, that it might become an object of devotion to the faithful.

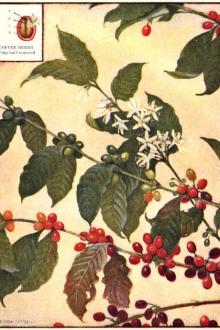

The Abbey of Brantome on the Dronne (Dep. Dordogne) was originally, like Marmoutier, a cavern monastery, and like those of Marmoutier, the monks waxing fat, they kicked and abandoned the grottoes for a stately structural monastery. The beautiful Romanesque tower of the church stands on top of a rock that is honeycombed with their cells. The church, consisting of nave only, is of marvellous beauty, early pointed, and built on a curve, as there was but little space to spare between the river and the cliffs. Unhappily church and cloister were delivered over to be "restored" by that arch-wrecker, Abbadie, who has done such incalculable mischief in Perigord and the Angoumois, and his hoof-mark is visible here. The monks, not content with a sumptuous Gothic abbey, pulled it down and built one in the baroque style, and had but just completed it when the Revolution broke out "and the flood came and swept them all away." In the court behind this modern structure is to be seen the cliff perforated with caves; it has, however, been cut back to the detriment of these, so that we have them shorn of their faces. Nevertheless they are interesting. The old monolithic chapel of the monastery remains, turned into a pigeonry, and with the steps left that gave access to the pulpit, and two pieces of sculpture on a very large scale, cut out of the living rock. One represents the Crucifixion with SS. Mary and John; the other has been variously explained as the Last Judgment or the Triumph of Death. It perhaps represents the Triumph of Christ over Death. His figure and the kneeling figures of His Mother and the Beloved Disciple were, however, never completed, and remain in the rough.

Beneath the figure of Christ is Death, figured by a head surmounted by a crown of bones, and a crest representing a spectre armed with a club. On each side is an angel blowing a trumpet. Below are ranged a dozen heads of popes, bishops, princes, knights, and ladies, in boxes to represent graves.

Sculpture in the cave monastery of Brantome. The figure of Christ was never completed. Below is a head crowned with bones, for Death, with Time as crest. Below, in boxes, are the dead, of various degrees.]

In the front of this huge piece of sculpture are trestles planted in the ground to support planks to serve as tables when the Brantomois desire to have a banquet and a dance.

The sculpture above described is not earlier than the sixteenth century. A few paces from it, in the same line and almost under the tower, is another grotto called _La Babayou_--that is to say "of the statue," and it probably at one time enshrined an image of a saint. On the left of the subterranean church is the fountain of the little Cut-throat already mentioned. S. Sicarius, whose relics were the great "draw" to Brantome in the Middle Ages, was supposed to have been one of the Innocents slain by Herod; and the relics were also supposed to have been given to the abbey by Charlemagne. As there was no historic evidence that Charles the Great ever had a set of little bones passed off on him as those of the Innocent, or that he ever made a present to the abbey of a relic, it will be seen that a good deal of supposition goes to the story. As I have said before, how it was that the child of a Hebrew mother acquired a Latin name, and that one so peculiar, we are not informed.

Outside the town gate are other large excavations that are supposed to have formed a temple of Mithras, but this is mere conjecture. The largest is now employed as a _Tir_--a shooting gallery. That there were buildings connected with it is seen by the holes in the rock to receive rafters.

S. Maximus, Bishop of Riez, who died in 460, was born at Chateau Redon, near Digne, and he entered the monastic life on the isle of Lerins, under S. Honoratus, and when that saint was raised in 426 to the episcopal throne of Arles, Maximus succeeded him as Abbot of Lerins. But this monastery was becoming crowded, and Maximus pined for the solitary life, so one day he took a boat, crossed to the mainland, and plunged into the wild country about the river Verdon, that has sawn for itself a chasm through the limestone; where it debouches, he planted himself at a place since called Moustier-Ste-Marie. The lips of the crevasse are linked by a chain, with a gilt star hanging in the midst, little under 690 feet above the bed of the torrent. No one knows when this star was hung there, but it is supposed to have been an _ex voto_ of a chevalier, de Blac. Within the ravine, reached by a narrow goat-path, were caves in the cliffs, and into one of these Maximus retired in 434 and was speedily followed by other solitaries. The caves are still there, the faces walled up, but as at Liguge, and as at Marmoutier, and as at Brantome, so was it here. As the monastery grew rich, the solitaries crawled out of their holes into which the sun never shone, and erected their residence at the opening of the ravine. A chapel remains, founded by Charlemagne, but rebuilt in the fourteenth or fifteenth century, reached by a stair protected by a parapet.

Moustier was famous at the close of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth century for its faience, with elegant designs and good colouring. Specimens are

Free e-book «Castles and Cave Dwellings of Europe - Sabine Baring-Gould (books to read to improve english TXT) 📗» - read online now

Similar e-books:

Comments (0)