All About Coffee - William H. Ukers (best novel books to read .TXT) 📗

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Book online «All About Coffee - William H. Ukers (best novel books to read .TXT) 📗». Author William H. Ukers

In countries like India and Africa, the birds and monkeys eat the ripe coffee berries. The so-called "monkey coffee" of India, according to Arnold, is the undigested coffee beans passed through the alimentary canal of the animal.

The pulp surrounding the coffee beans is at present of no commercial importance. Although efforts have been made at various times by natives to use it as a food, its flavor has not gained any great popularity, and the birds are permitted a monopoly of the pulp as a food. From the human standpoint the pulp, or sarcocarp, as it is scientifically called, is rather an annoyance, as it must be removed in order to procure the beans. This is done in one of two ways. The first is known as the dry method, in which the entire fruit is allowed to dry, and is then cracked open. The second way is called the wet method; the sarcocarp is removed by machine, and two wet, slimy seed packets are obtained. These packets, which look for all the world like seeds, are allowed to dry in such a way that fermentation takes place. This rids them of all the slime; and, after they are thoroughly dry, the endocarp, the so-called parchment covering, is easily cracked open and removed. At the same time that the parchment is removed, a thin silvery membrane, the silver skin, beneath the parchment, comes off, too. There are always small fragments of this silver skin to be found in the groove of the coffee bean contained within the parchment packet.

From a photograph made at Dramaga, Preanger, Java, in 1907

We have said that the coffee tree yields from one to twelve pounds a year, but of course this varies with the individual tree and also with the region. In some countries the whole year's yield is less than 200 pounds per acre, while there is on record a patch in Brazil which yields about seventeen pounds to the tree, bringing the yield per acre much higher.

The beans do not retain their vitality for planting for any considerable length of time; and, if they are thoroughly dried, or are kept for longer than three or four months, they are useless for that purpose. It takes the seed about six weeks to germinate and to appear above ground. Trees raised from seed begin to blossom in about three years; but a good crop can not be expected of them for the first five or six years. Their usefulness, save in exceptional cases, is ended in about thirty years.

The coffee tree can be propagated in a way other than by seeds. The upright branches can be used as slips, which, after taking root, will produce seed-bearing laterals. The laterals themselves can not be used as slips. In Central America the natives sometimes use coffee uprights for fences and it is no uncommon sight to see the fence posts "growing."

The wood of the coffee tree is used also for cabinet work, as it is much stronger than many of the native woods, weighing about forty-three pounds to the cubic foot, having a crushing strength of 5,800 pounds per square inch, and a breaking strength of 10,900 pounds per square inch.

The propagation of the coffee plant by cutting has two distinct advantages over propagation by seed, in that it spares the expense of seed production, which is enormous, and it gives also a method of hybridization, which, if used, might lead not only to very interesting but also to very profitable results.

The hybridization of the coffee plant was taken up in a thoroughly scientific manner by the Dutch government at the experimental garden established at Bangelan, Java, in 1900. In his studies, twelve varieties of Coffea arabica are recognized by Dr. P.J.S. Cramer[95], namely:

Laurina, a hybrid of Coffea arabica with C. mauritiana, having small narrow leaves, stiff, dense branches, young leaves almost white, berry long and narrow, and beans narrow and oblong.

Murta, having small leaves, dense branches, beans as in the typical Coffea arabica, and the plant able to stand bitter cold.

Menosperma, a distinct type, with narrow leaves and bent-down branches resembling a willow, the berries seldom containing more than one seed.

This is a comparatively new species, discovered in the Tchad Lake district of West Africa in 1905. It is a small-beaned variety of Coffea liberica

Mokka (Coffea Mokkæ), having small leaves, dense foliage, small round berries, small round beans resembling split peas, and possessed of a stronger flavor than Coffea arabica.

Purpurescens, a red-leaved variety, comparable with the red-leaved hazel and copper beech, a little less productive than the Coffea arabica.

Variegata, having variegated leaves striped and spotted with white.

Amarella, having yellow berries, comparable with the white-fruited variety of the strawberry, raspberry, etc.

Bullata, having broad, curled leaves; stiff, thick, fragile branches, and round, fleshy berries containing a high percentage of empty beans.

Angustifolia, a narrow-leaved variety, with berries somewhat more oblong and, like the foregoing, a poor producer.

Erecta, a variety that is sturdier than the typical arabica, better suited to windy places, and having a production as in the common arabica.

Maragogipe, a well-defined variety with light green leaves having colored edges: berries large, broad, sometimes narrower in the middle; a light bearer, the whole crop sometimes being reduced to a couple of berries per tree.[96]

Columnaris, a vigorous variety, sometimes reaching a height of 25 feet, having leaves rounded at the base and rather broad, but a shy bearer, recommended for dry climates.

Coffea Stenophylla

Coffea arabica has a formidable rival in the species stenophylla. The flavor of this variety is pronounced by some as surpassing that of arabica. The great disadvantage of this plant is the fact that it requires so long a time before a yield of any value can be secured. Although the time required for the maturing of the crop is so long, when once the plantation begins to yield, the crop is as large as that of Coffea arabica, and occasionally somewhat larger. The leaves are smaller than any of the species described, and the flowers bear their parts in numbers varying from six to nine. The tree is a native of Sierra Leone, where it grows wild.

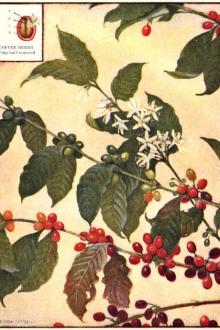

Copyright, 1909, by The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal

NEAR VIEW OF COFFEE BERRIES OF COFFEA ARABICA

Coffea Liberica

The bean of Coffea arabica, although the principal bean used in commerce, is not the only one; and it may not be out of place here to describe briefly some of the other varieties that are produced commercially. Coffea liberica is one of these plants. The quality of the beverage made from its berries is inferior to that of Coffea arabica, but the plant itself offers distinct advantages in its hardy growing qualities. This makes it attractive for hybridization.

Mantsaka or Café Sauvage—Madagascar

The Coffea liberica tree is much larger and sturdier than the Coffea arabica, and in its native haunts it reaches a height of 30 feet. It will grow in a much more torrid climate and can stand exposure to strong sunlight. The leaves are about twice as long as those of arabica, being six to twelve inches in length, and are very thick, tough, and leathery. The apex of the leaf is acute. The flowers are larger than those of arabica, and are borne in dense clusters. At any time during the season, the same tree may bear flowers, white or pinkish, and fragrant, or even green, together with fruits, some green, some ripe and of a brilliant red. The corolla has been known to have seven segments, though as a rule it has five. The fruits are large, round, and dull red; the pulps are not juicy, and are somewhat bitter. Unlike Coffea arabica, the ripened drupes do not fall from the trees, and so the picking can be delayed at the planter's convenience.

Col. I. Mature bean. Col. II. Embryo.

A. Coffea arabica, R. Coffea robusta, L. Coffea liberica

Among the allied Liberian species Dr. Cramer recognizes:

Abeokutæ, having small leaves of a bright green, flower buds often pink just before opening (in Liberian coffee never), fruit smaller with sharply striped red and yellow shiny skin, and producing somewhat smaller beans than Liberian coffee, but beans whose flavor and taste are praised by brokers;

Dewevrei, having curled edged leaves, stiff branches, thick-skinned berries, sometimes pink flowers, beans generally smaller than in C. liberica, but of little interest to the trade;

Arnoldiana, a species near to Coffea Abeokutæ having darker foliage and the even colored small berries;

Laurentii Gillet, a species not to be confused with the C. Laurentii belonging to the robusta coffee, but standing near to C. liberica, characterized by oblong rather than thin-skinned berries;

Excelsa, a vigorous, disease-resisting species discovered in 1905 by Aug. Chevalier in West Africa, in the region of the Chari River, not far from Lake Tchad. The broad, dark-green leaves have an under side of light green with a bluish tinge; the flowers are large and white, borne in axillary clusters of one to five; the berries are short and broad, in color crimson, the bean smaller than robusta, very like Mocha, but in color a bright yellow like liberica. The caffein content of the coffee is high, and the aroma is very pronounced;

Dybowskii, another disease-resisting variety similar to excelsa, but having different leaf and fruit characteristics;

Lamboray, having bent gutter-like leaves, and soft-skinned, oblong fruit;

Wanni Rukula, having large leaves, a vigorous growth, and small berries;

Coffea aruwimensis, being a mixture of different types.

Comments (0)