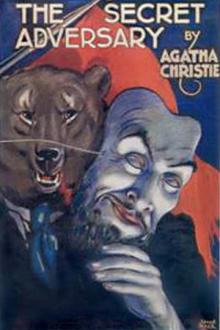

The Secret Adversary - Agatha Christie (good english books to read .txt) 📗

- Author: Agatha Christie

- Performer: 0451201205

Book online «The Secret Adversary - Agatha Christie (good english books to read .txt) 📗». Author Agatha Christie

“Whichever way you decide, good luck to you.

“Your sincere friend,

“MR. CARTER.”

Tuppence’s spirits rose mercurially. Mr. Carter’s warnings passed unheeded. The young lady had far too much confidence in herself to pay any heed to them.

With some reluctance she abandoned the interesting part she had sketched out for herself. Although she had no doubts of her own powers to sustain a role indefinitely, she had too much common sense not to recognize the force of Mr. Carter’s arguments.

There was still no word or message from Tommy, but the morning post brought a somewhat dirty postcard with the words: “It’s O.K.” scrawled upon it.

At ten-thirty Tuppence surveyed with pride a slightly battered tin trunk containing her new possessions. It was artistically corded. It was with a slight blush that she rang the bell and ordered it to be placed in a taxi. She drove to Paddington, and left the box in the cloak room. She then repaired with a handbag to the fastnesses of the ladies’ waiting-room. Ten minutes later a metamorphosed Tuppence walked demurely out of the station and entered a bus.

It was a few minutes past eleven when Tuppence again entered the hall of South Audley Mansions. Albert was on the look-out, attending to his duties in a somewhat desultory fashion. He did not immediately recognize Tuppence. When he did, his admiration was unbounded.

“Blest if I’d have known you! That rig-out’s top-hole.”

“Glad you like it, Albert,” replied Tuppence modestly. “By the way, am I your cousin, or am I not?”

“Your voice too,” cried the delighted boy. “It’s as English as anything! No, I said as a friend of mine knew a young gal. Annie wasn’t best pleased. She’s stopped on till to-day—to oblige, she said, but really it’s so as to put you against the place.”

“Nice girl,” said Tuppence.

Albert suspected no irony.

“She’s style about her, and keeps her silver a treat—but, my word, ain’t she got a temper. Are you going up now, miss? Step inside the lift. No. 20 did you say?” And he winked.

Tuppence quelled him with a stern glance, and stepped inside.

As she rang the bell of No. 20 she was conscious of Albert’s eyes slowly descending beneath the level of the floor.

A smart young woman opened the door.

“I’ve come about the place,” said Tuppence.

“It’s a rotten place,” said the young woman without hesitation. “Regular old cat—always interfering. Accused me of tampering with her letters. Me! The flap was half undone anyway. There’s never anything in the waste-paper basket—she burns everything. She’s a wrong ‘un, that’s what she is. Swell clothes, but no class. Cook knows something about her—but she won’t tell—scared to death of her. And suspicious! She’s on to you in a minute if you as much as speak to a fellow. I can tell you——”

But what more Annie could tell, Tuppence was never destined to learn, for at that moment a clear voice with a peculiarly steely ring to it called:

“Annie!”

The smart young woman jumped as if she had been shot.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Who are you talking to?”

“It’s a young woman about the situation, ma’am.”

“Show her in then. At once.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Tuppence was ushered into a room on the right of the long passage. A woman was standing by the fireplace. She was no longer in her first youth, and the beauty she undeniably possessed was hardened and coarsened. In her youth she must have been dazzling. Her pale gold hair, owing a slight assistance to art, was coiled low on her neck, her eyes, of a piercing electric blue, seemed to possess a faculty of boring into the very soul of the person she was looking at. Her exquisite figure was enhanced by a wonderful gown of indigo charmeuse. And yet, despite her swaying grace, and the almost ethereal beauty of her face, you felt instinctively the presence of something hard and menacing, a kind of metallic strength that found expression in the tones of her voice and in that gimlet-like quality of her eyes.

For the first time Tuppence felt afraid. She had not feared Whittington, but this woman was different. As if fascinated, she watched the long cruel line of the red curving mouth, and again she felt that sensation of panic pass over her. Her usual self-confidence deserted her. Vaguely she felt that deceiving this woman would be very different to deceiving Whittington. Mr. Carter’s warning recurred to her mind. Here, indeed, she might expect no mercy.

Fighting down that instinct of panic which urged her to turn tail and run without further delay, Tuppence returned the lady’s gaze firmly and respectfully.

As though that first scrutiny had been satisfactory, Mrs. Vandemeyer motioned to a chair.

“You can sit down. How did you hear I wanted a house-parlourmaid?”

“Through a friend who knows the lift boy here. He thought the place might suit me.”

Again that basilisk glance seemed to pierce her through.

“You speak like an educated girl?”

Glibly enough, Tuppence ran through her imaginary career on the lines suggested by Mr. Carter. It seemed to her, as she did so, that the tension of Mrs. Vandemeyer’s attitude relaxed.

“I see,” she remarked at length. “Is there anyone I can write to for a reference?”

“I lived last with a Miss Dufferin, The Parsonage, Llanelly. I was with her two years.”

“And then you thought you would get more money by coming to London, I suppose? Well, it doesn’t matter to me. I will give you £50—£60—whatever you want. You can come in at once?”

“Yes, ma’am. To-day, if you like. My box is at Paddington.”

“Go and fetch it in a taxi, then. It’s an easy place. I am out a good deal. By the way, what’s your name?”

“Prudence Cooper, ma’am.”

“Very well, Prudence. Go away and fetch your box. I shall be out to lunch. The cook will show you where everything is.”

“Thank you, ma’am.”

Tuppence withdrew. The smart Annie was not in evidence. In the hall below a magnificent hall porter had relegated Albert to the background. Tuppence did not even glance at him as she passed meekly out.

The adventure had begun, but she felt less elated than she had done earlier in the morning. It crossed her mind that if the unknown Jane Finn had fallen into the hands of Mrs. Vandemeyer, it was likely to have gone hard with her.

CHAPTER X. ENTER SIR JAMES PEEL EDGERTON

TUPPENCE betrayed no awkwardness in her new duties. The daughters of the archdeacon were well grounded in household tasks. They were also experts in training a “raw girl,” the inevitable result being that the raw girl, once trained, departed elsewhere where her newly acquired knowledge commanded a more substantial remuneration than the archdeacon’s meagre purse allowed.

Tuppence had therefore very little fear of proving inefficient. Mrs. Vandemeyer’s cook puzzled her. She evidently went in deadly terror of her mistress. The girl thought it probable that the other woman had some hold over her. For the rest, she cooked like a chef, as Tuppence had an opportunity of judging that evening. Mrs. Vandemeyer was expecting a guest to dinner, and Tuppence accordingly laid the beautifully polished table for two. She was a little exercised in her own mind as to this visitor. It was highly possible that it might prove to be Whittington. Although she felt fairly confident that he would not recognize her, yet she would have been better pleased had the guest proved to be a total stranger. However, there was nothing for it but to hope for the best.

At a few minutes past eight the front door bell rang, and Tuppence went to answer it with some inward trepidation. She was relieved to see that the visitor was the second of the two men whom Tommy had taken upon himself to follow.

He gave his name as Count Stepanov. Tuppence announced him, and Mrs. Vandemeyer rose from her seat on a low divan with a quick murmur of pleasure.

“It is delightful to see you, Boris Ivanovitch,” she said.

“And you, madame!” He bowed low over her hand.

Tuppence returned to the kitchen.

“Count Stepanov, or some such,” she remarked, and affecting a frank and unvarnished curiosity: “Who’s he?”

“A Russian gentleman, I believe.”

“Come here much?”

“Once in a while. What d’you want to know for?”

“Fancied he might be sweet on the missus, that’s all,” explained the girl, adding with an appearance of sulkiness: “How you do take one up!”

“I’m not quite easy in my mind about the soufflé,” explained the other.

“You know something,” thought Tuppence to herself, but aloud she only said: “Going to dish up now? Right-o.”

Whilst waiting at table, Tuppence listened closely to all that was said. She remembered that this was one of the men Tommy was shadowing when she had last seen him. Already, although she would hardly admit it, she was becoming uneasy about her partner. Where was he? Why had no word of any kind come from him? She had arranged before leaving the Ritz to have all letters or messages sent on at once by special messenger to a small stationer’s shop near at hand where Albert was to call in frequently. True, it was only yesterday morning that she had parted from Tommy, and she told herself that any anxiety on his behalf would be absurd. Still, it was strange that he had sent no word of any kind.

But, listen as she might, the conversation presented no clue. Boris and Mrs. Vandemeyer talked on purely indifferent subjects: plays they had seen, new dances, and the latest society gossip. After dinner they repaired to the small boudoir where Mrs. Vandemeyer, stretched on the divan, looked more wickedly beautiful than ever. Tuppence brought in the coffee and liqueurs and unwillingly retired. As she did so, she heard Boris say:

“New, isn’t she?”

“She came in to-day. The other was a fiend. This girl seems all right. She waits well.”

Tuppence lingered a moment longer by the door which she had carefully neglected to close, and heard him say:

“Quite safe, I suppose?”

“Really, Boris, you are absurdly suspicious. I believe she’s the cousin of the hall porter, or something of the kind. And nobody even dreams that I have any connection with our—mutual friend, Mr. Brown.”

“For heaven’s sake, be careful, Rita. That door isn’t shut.”

“Well, shut it then,” laughed the woman.

Tuppence removed herself speedily.

She dared not absent herself longer from the back premises, but she cleared away and washed up with a breathless speed acquired in hospital. Then she slipped quietly back to the boudoir door. The cook, more leisurely, was still busy in the kitchen and, if she missed the other, would only suppose her to be turning down the beds.

Alas! The conversation inside was being carried on in too low a tone to permit of her hearing anything of it. She dared not reopen the door, however gently. Mrs. Vandemeyer was sitting almost facing it, and Tuppence respected her mistress’s lynx-eyed powers of observation.

Nevertheless, she felt she would give a good deal to overhear what was going on. Possibly, if anything unforeseen had happened, she might get news of Tommy. For some moments she reflected desperately, then her face brightened. She went quickly along the passage to Mrs. Vandemeyer’s bedroom, which had long French windows leading on to a balcony that ran the length of the flat. Slipping quickly through the window, Tuppence crept noiselessly along till she reached the boudoir window. As she had thought it stood a little ajar, and the voices within were plainly audible.

Tuppence listened attentively, but there was no mention of anything that could be twisted to apply to Tommy. Mrs. Vandemeyer and the Russian seemed to be at variance over some matter, and finally the latter exclaimed bitterly:

“With your persistent recklessness, you will end by ruining us!”

“Bah!” laughed the woman. “Notoriety of the right kind is the best way of disarming suspicion. You will realize that one of these days—perhaps sooner than you think!”

“In the meantime, you are going about everywhere with Peel Edgerton. Not only is he, perhaps, the most celebrated K.C. in England, but his special hobby is criminology! It is madness!”

“I know

Comments (0)