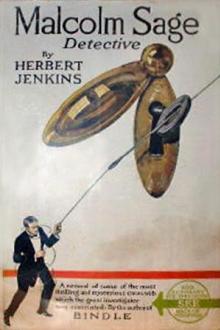

Malcolm Sage, Detective - Herbert George Jenkins (books to read to get smarter txt) 📗

- Author: Herbert George Jenkins

- Performer: -

Book online «Malcolm Sage, Detective - Herbert George Jenkins (books to read to get smarter txt) 📗». Author Herbert George Jenkins

"On the contrary, he is an extremely stupid creature," was the reply.

"He is continually losing himself. Only yesterday morning I myself

found him wandering about the corridor leading to my own bedroom.

Walters has also mentioned the matter to me."

Sir Lyster then passed on to the guests. They comprised Mrs. Selton, an aunt of Sir Lyster; Sir Jeffrey and Lady Trawlor, old friends of their hostess; Lady Whyndale and her two daughters. There were also Mr. Gerald Nash, M. P., and Mr. and Mrs. Richard Winnington, old friends of Sir Lyster and Lady Grayne.

"Later, I may require a list of the guests," said Malcolm Sage, when Sir Lyster had completed his account. "You said, I think, that the key of the safe was sometimes left in an accessible place?"

"Yes, in a drawer."

"So that anyone having access to the room could easily have taken a wax impression."

"Sir Lyster flushed slightly.

"There is no one——" he began.

"There is always a potential someone," corrected Malcolm Sage, raising his eyes suddenly and fixing them full upon Sir Lyster.

"The question is, Sage," broke in Mr. Llewellyn John tactfully, "what are we to do?"

"I should first like to see the inside of the safe and the dummy packet," said Malcolm Sage, rising. "No, I will open it myself if you will give me the key," he added, as Sir Lyster rose and moved over to the safe.

Taking the key, Malcolm Sage kneeled before the safe door and, by the light of an electric torch, surveyed the whole of the surface with keen-sighted eyes. Then placing the key in the lock he turned it, and swung back the door, revealing a long official envelope as the sole contents. This he examined carefully without touching it, his head thrust inside the safe.

"Is this the same envelope as that in which the document was enclosed?" he enquired, without looking round.

The three men had risen and were grouped behind Malcolm Sage, watching him with keen interest.

"It's the same kind of envelope, but——" began

Sir Lyster, when Lord Beamdale interrupted.

"It's the envelope itself," he said. "I noticed that the right-hand top corner was bent in rather a peculiar manner."

Malcolm Sage rose and, taking out the envelope, carefully examined the damaged corner, which was bent and slightly torn.

"Yes, it's the same," cried Mr. Llewellyn John. "I remember tearing it myself when putting in the document."

"How many leaves of paper were there?" enquired Malcolm Sage.

"Eight, I think," replied Sir Lyster.

"Nine," corrected Lord Beamdale. "There was a leaf in front blank but for the words, 'Plans Department.'"

"Have you another document from the same Department?" enquired

Malcolm Sage of Sir Lyster.

"Several."

"I should like to see one."

Sir Lyster left the room, and Malcolm Sage removed the contents of the envelope. Carefully counting nine leaves of blank white foolscap, he bent down over the paper, with his face almost touching it.

When Sir Lyster re-entered with another document in his hand Malcolm Sage took it from him and proceeded to subject it to an equally close scrutiny, holding up to the light each sheet in succession.

"I suppose, Sir Lyster, you don't by any chance use scent?" enquired

Malcolm Sage without looking up.

"Mr. Sage!" Sir Lyster was on his dignity.

"I see you don't," was Malcolm Sage's calm comment as he resumed his examination of the dummy document. Replacing it in the envelope, he returned it to the safe, closed the door, locked it, and put the key in his pocket.

"Well! what do you make of it?" cried Mr. Llewellyn John eagerly.

"We shall have to take the Postmaster-general into our confidence."

"Woldington!" cried Mr. Llewellyn John in astonishment. "Why."

Sir Lyster looked surprised, whilst Lord Beamdale appeared almost interested.

"Because we shall probably require his help."

"How?" enquired Sir Lyster.

"Well, it's rather dangerous to tamper with His Majesty's mails without the connivance of St. Martins-le-Grand," was the dry retort.

"But——" began Mr. Llewellyn John, when suddenly he stopped short.

Malcolm Sage had walked over to where his overcoat lay, and was deliberately getting into it.

"You're not going, Mr. Sage?" Sir Lyster's granite-like control seemed momentarily to forsake him. "What do you advise us to do?"

"Get some sleep," was the quiet reply.

"But aren't you going to search for——?" He paused as Malcolm Sage turned and looked full at him.

"A search would involve the very publicity you are anxious to avoid," was the reply.

"But——" began Mr. Llewellyn John, when Malcolm Sage interrupted him.

"The only effective search would be to surround the house with police, and allow each occupant to pass through the cordon after having been stripped. The house would then have to be gone through; carpets and boards pulled up; mattresses ripped open; chairs——"

"I agree with Mr. Sage," said Sir Lyster, looking across at the

Prime Minister coldly.

"Had I been a magazine detective I should have known exactly where to find the missing document," said Malcolm Sage. "As I am not"—he turned to Sir Lyster—"it will be necessary for you to leave a note for your butler telling him that you have dropped somewhere about the house the key of this safe, and instructing him to have a thorough search made for it. You might casually mention the loss at breakfast, and refer to an important document inside the safe which you must have on Monday morning. Perhaps the Prime Minister will suggest telephoning to town for a man to come down to force the safe should the key not be found."

Malcolm Sage paused. The others were gazing at him with keen interest.

"Leave the note unfolded in a conspicuous place where anyone can see it," he continued.

"I'll put it on the hall-table," said Sir Lyster.

Malcolm Sage nodded.

"It is desirable that you should all appear to be in the best of spirits." There was a fluttering at the corners of Malcolm Sage's mouth, as he lifted his eyes for a second to the almost lugubrious countenance of Lord Beamdale. "Under no circumstances refer to the robbery, even amongst yourselves. Try to forget it."

"But how will that help?" enquired Mr. Llewellyn John, whose nature rendered him singularly ill-adapted to a walking-on part.

"I will ask you, sir," said Malcolm Sage, turning to him, "to give me a letter to Mr. Woldington, asking him to do as I request. I will give him the details."

"But why is it necessary to tell him?" demanded Sir Lyster.

"That I will explain to you to-morrow. That will be Monday," explained Malcolm Sage, "earlier if possible. A few lines will do," he added, turning to Mr. Llewellyn John.

"I suppose we must," said the Prime Minister, looking from Sir

Lyster to Lord Beamdale.

"I hope to call before lunch," said Malcolm Sage, "but as Mr. Le Sage from the Foreign Office. You will refuse to discuss official matters until Monday. I shall probably ask you to introduce me to everyone you can. It may happen that I shall disappear suddenly."

"But cannot you be a little less mysterious?" said Sir Lyster, with a touch of asperity in his voice.

"There is nothing mysterious," replied Malcolm Sage. "It seems quite obvious. Everything depends upon how clever the thief is." He looked up suddenly, his gaze passing from one to another of the bewildered Ministers.

"It's by no means obvious to me," cried Mr. Llewellyn John, complainingly.

"By the way, Sir Lyster, how many cars have you in the garage?" enquired Malcolm Sage. "In case we want them," he added.

"I have two, and there are"—he paused for a moment—"five others," he added; "seven in all."

"Any carriages, or dog-carts?"

"No. We have no horses."

"Bicycles?"

"A few of the servants have them," replied Sir Lyster, a little impatiently.

"The bicycles are also kept in the garage, I take it?"

"They are." This time there was no mistaking the note of irritation in Sir Lyster's voice.

"There may be several messengers from Whitehall to-morrow," said Malcolm Sage, after a pause. "Please keep them waiting until they show signs of impatience. It is important. Whatever happens here, it would be better not to acquaint the police—whatever happens," he added with emphasis. "And now, sir"—he turned to Mr. Llewellyn John—"I should like that note to the Postmaster-general."

Mr. Llewellyn John sat down reluctantly at a table and wrote a note.

"But suppose the thief hands the document to an accomplice?" said

Sir Lyster presently, with something like emotion in his voice.

"That's exactly what I am supposing," was Malcolm Sage's reply and, taking the note that Mr. Llewellyn John held out to him, he placed it in his breast pocket, buttoned up his overcoat, and walked across to the window through which he had entered. With one hand upon the curtain he turned.

"If I call you may notice that I have acquired a slight foreign accent," he said, and with that he slipped behind the curtain. A moment later the sound was heard of the window being quietly opened and then shut again.

"Well, I'm damned!" cried Lord Beamdale, and for the moment Mr.

Llewelyln John and Sir Lyster forgot their surprise at Malcolm

Sage's actions in their astonishment at their colleague's remark.

When Mr. Walters descended the broad staircase of The Towers on the Sunday morning he found two things to disturb him—Sir Lyster's note on the hall-table, and the Japanese valet "lost" in the conservatory.

He read the one with attention, and rebuked the other with acrimony.

Having failed to find the missing key himself, he proceeded to the

housekeeper's room, and poured into the large and receptive ear of

Mrs. Eames the story of his woes.

"And this a Sunday too," the housekeeper was just remarking, in a fat, comfortable voice, when Richards, the chauffeur, burst unceremoniously into the room.

"Someone's taken the pencils from all the magnetos," he shouted angrily, his face moist with heat and lubricant.

"Is that your only excuse for bursting into a lady's room without knocking?" enquired Mr. Walters, with an austere dignity he had copied directly from Sir Lyster. "If you apply to me presently I will lend you a pencil. In the meantime——"

"But it's burglars. They've broken into the garage and taken the pencils from every magneto, every blinkin' one," he added by way of emphasis.

At the mention of the word "burglars," Mr. Walters's professional composure of feature momentarily forsook him, and his jaw dropped. Recovering himself instantly, however, he hastened out of the room, closely followed by Richards, leaving Mrs. Eames speechless, the oval cameo locket heaving up and down upon her indignant black-silk bosom. A man had sworn in her presence and had departed unrebuked.

On reaching the garage Mr. Walters gazed vaguely about him. He was entirely unversed in mechanics, and Richards persisted in pouring forth technicalities that bewildered him. The chauffeur also cursed loudly and with inspiration, until reminded that it was Sunday, when he lowered his voice, at the same time increasing the density of his language.

Mr. Walters was frankly disappointed. There, was no outward sign of burglars. At length he turned interrogatingly to Richards.

"Just a-goin' to tune 'em up I was," explained Richards for the twentieth time, "when I found the bloomin' engines had gone whonky, then——"

"Found the engines had gone what?" enquired Mr. Walters.

"Whonky, dud, na-poo," explained Richards illuminatingly, whilst Mr. Walters gazed at him icily. "Then in comes Davies," he continued, nodding in the direction of a little round-faced man, with "chauffeur" written on every inch of him "and 'e couldn't get 'is blinkin' 'arp to 'urn neither. Then we starts a-lookin' round, when lo and be'old! what do we find? Some streamin', saturated son of sin an' whiskers 'as pinched the ruddy pencils out of the scarlet magnetos."

"The float's gone from my carburettor."

The voice came from a long, lean man who appeared suddenly out of the shadows at the far-end of the garage.

Without a word Richards and Davies dashed each to a car. A minute later two yells announced that the floats from their carburettors also had disappeared.

Later Richards told how that morning he had found the door of the garage unfastened, although he was certain that he had locked it the night before.

This was sufficient for Mr. Walters. Fleeing from the bewildering flood of technicalities and profanity of the three chauffeurs, he made his way direct to Sir Lyster's room. Here he told his tale, and was instructed instantly to telephone to the police.

At the telephone further trouble awaited him.

Comments (0)