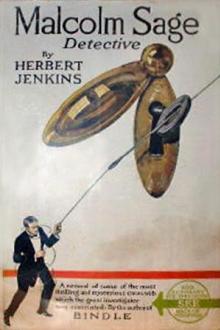

Malcolm Sage, Detective - Herbert George Jenkins (books to read to get smarter txt) 📗

- Author: Herbert George Jenkins

- Performer: -

Book online «Malcolm Sage, Detective - Herbert George Jenkins (books to read to get smarter txt) 📗». Author Herbert George Jenkins

The inspector merely stared. Words had forsaken him for the moment.

"It was then necessary to wait until the ink in Miss Crayne's pen had become exhausted, and she had to replenish her supply of paper from her father's study. After that discovery was inevitable."

"But suppose she had denied it?" questioned the inspector.

"There was the ink which she alone used, and which I could identify," was the reply.

"Why did you ask Gray to be present?" enquired Freynes.

"As his name had been associated with the scandal it seemed only fair," remarked Malcolm Sage, then turning to Inspector Murdy he said, "I shall leave it to you, Murdy, to see that a proper confession is obtained. The case has had such publicity that Mr. Blade's innocence must be made equally public."

"You may trust me, Mr. Sage," said the inspector. "But why did the curate refuse to say anything?"

"Because he is a high-minded and chivalrous gentleman," was the quiet reply.

"He knew?" cried Freynes.

"Obviously," said Malcolm Sage. "It is the only explanation of his silence. I taxed him with it after the girl had been taken away, and he acknowledged that his suspicions amounted almost to certainty."

"Yet he stayed behind," murmured the inspector with the air of a man who does not understand. "I wonder why?"

"To minister to the afflicted, Murdy," said Malcolm Sage. "That is the mission of the Church."

"I suppose you meant that French case when you referred to the 'master-key,'" remarked the inspector, as if to change the subject.

Malcolm Sage nodded.

"But how do you account for Miss Crayne writing such letters about herself?" enquired the inspector, with a puzzled expression in his eyes. "Pretty funny letters some of them for a parson's daughter."

"I'm not a pathologist, Murdy," remarked Malcolm Sage drily, "but when you try to suppress hysteria in a young girl by sternness, it's about as effectual as putting ointment on a plague-spot."

"Sex-repression?" queried Freynes.

Malcolm Sage shrugged his shoulders; then after a pause, during which he lighted the pipe he had just re-filled, he added:

"When you are next in Great Russell Street, drop in at the British Museum and look at the bust of Faustina. You will see that her chin is similar in modelling to that of Miss Crayne. The girl was apparently very much attracted to Blade, and proceeded to weave what was no doubt to her a romance, later it became an obsession. It all goes to show the necessity for pathological consideration of certain crimes."

"But who was Faustina?" enquired the inspector, unable to follow the drift of the conversation.

"Faustina," remarked Malcolm Sage, "was the domestic fly in the philosophical ointment of an emperor," and Inspector Murdy laughed; for, knowing nothing of the marriage or the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, it seemed to him the only thing to do.

CHAPTER XV THE MISSING HEAVYWEIGHT I"Mr. Doulton, sir. Very important." Rogers had carefully assimilated his master's theory of the economy of words, sometimes even to the point of obscuring his meaning.

Taking the last piece of toast from the rack, Malcolm Sage with great deliberation proceeded to butter it. Then, with a nod to the waiting Rogers, he poured out the last cup of coffee the pot contained.

A moment later the door opened to admit a clean-shaven little man of about fifty, prosperous in build and appearance; but obviously labouring under some great excitement. His breath came in short, spasmodic gasps. His thin sandy hair had clearly not been brushed since the day before, whilst his chin and upper lip bore obvious traces of a night's growth of beard. He seemed on the point of collapse.

"He's gone—disappeared!" he burst out, as Rogers closed the door behind him. Malcolm Sage rose, motioned his caller to a chair at the table, and resumed his own seat.

"Had breakfast?" he enquired quietly, resuming his occupation of getting the toast carefully and artistically buttered.

"Good God, man!" exploded Mr. Doulton, almost hysterically. "Don't you understand? Burns has disappeared!"

"I gathered as much," said Malcolm Sage calmly, as he reached for the marmalade.

"Pond telephoned from Stainton," continued Mr. Doulton. "I was in Fed. I got dressed, and came round here at once. I——" he stopped suddenly, as Rogers entered with a fresh relay of coffee. Without a word he proceeded to pour out a cup for Mr. Doulton, who, after a moment's hesitation, drank it greedily.

Rogers glanced interrogatingly from the dish that had contained eggs and bacon to Malcolm Sage, who nodded.

When he had withdrawn, Mr. Doulton opened his mouth to speak, then closed it again and gazed at Malcolm Sage, who, having superimposed upon the butter a delicate amber film of marmalade, proceeded to cut up the toast into a series of triangles. Apparently it was the only thing in life that interested him.

For weeks past the British and American sporting world had thought and talked of nothing but the forthcoming fight between Charley Burns and Bob Jefferson for the heavyweight championship of the world. The event was due to take place two days hence at the Olympia for a purse of 40,000 pounds offered by Mr. Montague Doulton, the prince of impresarios.

Never had a contest been looked forward to with greater eagerness than the Burns v. Jefferson match. A great change had come over public opinion in regard to prize-fighting, thanks to the elevating influence of Mr. Doulton. It was no longer referred to as "brutalising" and "debasing." Refined and nice-minded people found themselves mildly interested and patriotically hopeful that Charley Burns, the British champion, would win. In two years Mr. Doulton had achieved what the National Sporting Club had failed to do in a quarter of a century.

Long and patiently he had laboured to bring about this match, which many thought would prove the keystone to the arch of Burns's fame, incidentally to that of the impresario himself.

"And now he's disappeared—clean gone." Mr. Doulton almost sobbed.

"Tell me."

Malcolm Sage looked up from his plate, the last triangle of toast poised between finger and thumb.

In short staccatoed sentences, like bursts from a machine-gun, Mr.

Doulton proceeded to tell his story.

That morning at six o'clock, when Alf Pond, Burns's trainer, had entered his room to warn him that it was time to get up, he found it unoccupied. At first he thought that Burns had gone down before him; but immediately his eye fell on the bed, and he saw that it had not been slept in, he became alarmed.

Going to the bedroom door, he had shouted to the sparring-partners, and soon the champion's room was filled with men in various stages of déshabille.

Only for a moment, however, had they remained inactive. At Alf Pond's word of command they had spread helter-skelter over the house and grounds, causing the early morning air to echo with their shouts for "Charley."

When at length he became assured that Burns had disappeared, Alf

Pond telephoned first to Mr. Doulton and then to Mr. Papwith,

Burns's backer.

"I told Pond to do nothing and tell no one," said Mr. Doulton, in conclusion, "and when I left my rooms my man was trying to get through to Papwith to ask him to keep the story to himself."

Malcolm Sage nodded approval.

"Now, what's to be done?" He looked at Malcolm Sage with the air of a man who has just told a doctor of his alarming symptoms, and almost breathlessly awaits the verdict.

"Breakfast, a shave, then we'll motor down to Stainton," and Malcolm Sage proceeded to fill his briar, his whole attention absorbed in the operation.

A moment later Rogers entered with a fresh supply of eggs and bacon. Mr. Doulton shook his head. Instinctively his hand had gone up to his unshaven chin. It was probably the first time in his life that he had sat at table without shaving. He prided himself upon his personal appearance. In his younger days he had been known as "Dandy Doulton."

"The car in half an hour, Rogers," said Malcolm Sage, as he rose from the table. "When you've finished," he said, turning to Mr. Doulton, "Rogers will give you hot water, a razor and anything else you want. By the time you have shaved I shall be ready."

"But don't you see——Think what it——" began Mr. Doulton.

"An empty stomach neither sees nor thinks," was Malcolm Sage's oracular retort, and he went over to the window and seated himself at his writing-table.

For the next half-hour he was engaged with his correspondence, and in telephoning instructions to his office.

By the time Mr. Doulton had breakfasted and shaved, the car was at the door.

During the run to Stainton both men were silent. Mr. Doulton was speculating as to what would happen at the Olympia on the following night if Burns failed to appear, whilst Malcolm Sage was occupied with thoughts, the object of which was to prevent such a catastrophe.

"They're sure to say it's a yellow streak," Mr. Doulton burst out on one occasion; but, as Malcolm Sage took no notice of the remark, he subsided into silence, and the car hummed its way along the Portsmouth Road.

Burns's training-quarters were situated at Stainton, near Guildford. Here, under the vigilant eye of Alf Pond, and with the help of a large retinue of sparring-partners, he was getting himself into what had come to be called "Burns's condition," which meant that he would enter the ring trained to the minute. Never did athlete work more conscientiously than Charley Burns.

As the car turned into a side road, flanked on either hand by elms,

Mr. Doulton tapped on the wind-screen, and Tims pulled up. Malcolm

Sage had requested that the car be stopped a hundred yards before it

reached "The Grove," where the training quarters were situated.

"Wait for me here," he said, as he got out.

"It's the first gate on the right," said Mr. Doulton.

Walking slowly away from the car, Malcolm Sage examined with great care the road itself. Presently he stopped and, taking from his pocket a steel spring-measure, he proceeded to measure a portion of the surface of the dusty roadway. Having made several entries in a note-book, he then turned back to the car, his eyes still on the road.

Instructing Tims to remain where he was, Malcolm Sage motioned to Mr.

Doulton to get out.

"This way," said Malcolm Sage, leading him to the extreme left-hand side of the road. Turning into the gates of "The Grove," they walked up the drive towards the house. In front stood a group of men in various and nondescript costumes.

As Malcolm Sage and Mr. Doulton approached, a man in a soiled white sweater and voluminous grey flannel trousers, generously turned up at the extremities, detached himself from the group and came towards them. He was puffy of face, with pouched eyes and a moist skin; yet in his day Alf Pond had been an unbeatable middle-weight, and the greatest master of ring-craft of his time; but that was nearly a generation ago.

In agonised silence he looked from Mr. Doulton to Malcolm Sage, then back again to Mr. Doulton. There was in his eyes the misery of despair.

The preliminary greetings over, Alf Pond led the way round to a large coach-house in the rear, which had been fitted up as a gymnasium. Here were to be seen all the appliances necessary to the training of a boxer for a great contest, including a roped ring at one end.

"He was here only yesterday." There was a world of tragedy and pathos in Alf Pond's tone. Something like a groan burst from the sparring-partners.

With a quick, comprehensive glance, Malcolm Sage seemed to take in every detail.

"It's a bad business, Pond," said Mr. Doulton, who found the mute despair of these hard-living, hard-hitting men rather embarrassing.

"What'd I better do?" queried Alf Pond.

"I've put the

Comments (0)