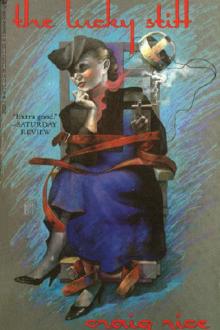

Lucky Stiff - Craig Rice (good book club books .TXT) 📗

- Author: Craig Rice

- Performer: -

Book online «Lucky Stiff - Craig Rice (good book club books .TXT) 📗». Author Craig Rice

When I’m sitting in the gloom

Of my lonely little room—

Jake turned his back to the stage and tried to forget the first time he’d heard that song, in the old Haywire Club, now the Orchid Bowl, sung by a girl with an untrained, off-key voice, a girl with tawny hair and big, gray-blue, almost smoky, eyes. He signaled the waiter for two more vodka collins, then looked at his wrist watch. Twenty-five minutes to twelve.

The audience objected loudly to Milly Dale’s leaving the stage, but they calmed down a little when the chorus romped down the steps onto the dance floor. They howled appreciatively at the comedians who followed the chorus. Then Milly Dale came back, in a black satin dress that fitted her like adhesive tape, struck a pose, and began to sing:

Dear jury,

If you think I’m the girl with the gun,

You can search me.

Dear jury—

“Jake!” Helene whispered. “I’ve just remembered—Jake, listen—”

“You can tell me when we get home,” Jake said. He rose. “Finish your drink and let’s get out of here.” His voice was harsh.

Helene took one quick glance at his face, slid her wrap over her shoulders, and rose without another word.

They paused for a moment at the bar. Milly Dale had gone through half of her strip act before an imaginary jury and was now down to the black satin bathing suit.

If you think I hid those letters,

Try and find them,

If you think I—

“Darling, “Helene said. “That song. Doesn’t it remind you of something—”

“It does,” Jake said, “and shut up.” It reminded him of that off-key voice. He said to the bartender, “A double rye, and quick.”

Helene glanced at him and added to the bartender, “Same for me, and please have our car brought around to the side door.”

When they left Milly Dale’s voice followed them.

Dear Jury—

If you—

“Hell!” Jake said, and slammed the car door when they got in.

There was silence all the way to the apartment building, all the way through the lobby and up the elevator. Once inside the apartment Helene let the dark green wool cape slide off her shoulders. “Coffee?” she asked. “Champagne? Or just a drink?”

“Never mind,” Jake said. He walked across the room and turned on the radio for the late news broadcast.

There was the buzz as the radio warmed up, and a commercial for a credit dentist. The station break, then the news announcer:

“Anna Marie St. Clair died in the electric chair at one minute after midnight this morning, with a smile on her lips— “

Jake switched it off and sank down on the couch.

“She was innocent,” Helene whispered. “I could have proved it.”

“A drink,” Jake said. “Get me a drink.”

He downed the glass of rye she put in his hand. Then he looked up at the pleasant, familiar room. There were flowers everywhere, the flowers he’d ordered and picked out for this occasion. There was, he knew, champagne being iced in the kitchenette. There was Helene in her pale green dress.

He hadn’t wanted their wedding anniversary to be like this. He’d wanted roses and champagne and laughter.

If only he could tell Helene the whole story. Anna Marie. The Clark Street saloon on the night of the murder. But he couldn’t. Not even to Helene could he give away the reason he’d kept his mouth shut all these weeks.

She looked at him, at the silent radio, and back at him again. Suddenly she caught her breath. So that was it. Helene made several unpleasant remarks to herself about being both tactless and an idiot.

“Jake. Darling.” She sat down beside him. He looked at her, his eyes full of misery.

“Don’t think about it. Don’t brood about it. It’s all over and done with.” She paused to light a cigarette for him. “After all, you said yourself there wasn’t anything we—you— could have done.”

Jake turned away. “That’s just the trouble,” he said. “There was.”

“You had us in a spot,” Jesse Conway said, “and you know it. We had to give in to your crazy scheme. But what’s in your mind? What comes next?”

“I don’t know,” Anna Marie said lightly. She sounded as though she didn’t care.

She looked out through the window of Jesse Conway’s limousine at the lights of Chicago’s streets flashing by. Funny to see lights again. Lights and people and automobiles. There was the marquee of a theater. Perhaps tomorrow she’d go to a movie. Funny to be able to go to a movie. Funny to be out of the cell. Funny to be alive at all.

“What time is it?” she asked.

“Quarter of eleven,” Jesse Conway said. “Now, look here, Anna Marie—”

“In an hour and fifteen minutes,” she said with a little laugh, “I’ll be dead.”

Jesse Conway started to speak, changed his mind, and shrugged his shoulders. At last he said, “Well, where do you want to go?”

“My apartment first,” Anna Marie said. “I suppose I can still get in.”

Jesse Conway cleared his throat in an embarrassed fashion. “I still have the key, you know. Tomorrow I was to go in and get all your clothes, and send them to your Aunt Bess out in Grove Junction.”

“I remember,” Anna Marie said coldly, “and you can go ahead as per schedule. Only I’m afraid Aunt Bess will have to wait.” She was silent for a few minutes, thinking. “I’ll find a safe hide-out in the morning. You can bring me the clothes and some other things, and money. I don’t suppose I can touch my own dough.”

“Hardly,” Jesse Conway said.

Anna Marie laughed. “That’s the hell of being a ghost. Oh, well. You can advance me whatever I need, and I’ll give it back to you when I’m through with this monkey business.”

“Whatever you say,” he said wearily. “But why the hide-out? Nobody’ll try to take you back to jail.”

“Because ghosts never appear in the daytime,” she told him.

The car stopped in front of a modest apartment building. The street was dark and deserted, but Anna Marie glanced around for possible spectators before she crossed the sidewalk. Jesse Conway unlocked a side entrance on the ground floor and turned on the lights. Anna Marie paused just inside the door and looked.

There was a thin film of dust on the yellow brocade love seat, with its wickedly simpering carved cupids. There was dust on the thick pile carpet, on the deep-cushioned chairs, and on the built-in bar. Some news photographer had left a flash bulb on the gilt coffee table.

“Big Joe Childers did me proud,” Anna Marie said. “Too bad some son-of-a-bitch killed him.”

She told Jesse Conway to wait for her and went on into the bedroom, which she had perversely decorated with muslin and dimity, a young girl’s four-poster bed, hooked rugs, and big, pale pink ribbon bows on the curtains. In it, her flamboyant beauty stood out like a firecracker in an old-fashioned garden, and she knew it.

While Jesse Conway waited impatiently and apprehensively in the next room, she poured handfuls of perfumed salts into the tub, ran in steaming water, and took a long, luxurious bath. Then she dressed, slowly and meticulously, reveling as much in the privacy as in the comforts of her room. To bathe and dress without one of those weasel-eyed female wardens watching—that was something!

Half an hour later she came back into the living room. Jesse Conway looked up, and gasped.

She wore a close-fitting, obviously costly, pale gray suit. The jacket was collarless, and fastened at her throat with a dull gold clasp. The skirt flared very slightly between her hip and her knee. Her tiny slippers were gray, and her incredibly sheer stockings were the exact color of her skin. There was a little gray pillbox hat on the back of her tawny head, and from it floated an immense, graceful, bright pink veil. She carried bright pink gloves, and the purse under her arm was made of wide, diagonal stripes of pink suede and gold kid.

“Good God!” Jesse Conway said. Then he took out his handkerchief, sponged his brow, and said, “But that’s the—those are the clothes—”

“It’s what I had on the night I was supposed to have shot Big Joe,” she said, smiling. “Becoming outfit, isn’t it?”

Jesse Conway said, “Very.” He looked at her again, closely. She’d made up her lovely face so that it was very pale. The lipstick she’d used was almost lavender. There was a deep smudge of purplish eye shadow on her lids.

“You look white as death,” Jesse Conway said. He bit the last word off suddenly.

“That’s the idea,” Anna Marie told him. Now give me about twenty bucks and you can tell me good night. Tomorrow come in and get all my clothes out of here, and all the make-up and stuff I left on top of the dresser. I’ll let you know where to send it, along with some more money.”

He rose and stood looking at her, twisting his hat brim between his fingers. At last he said, “Anna Marie, you’re insane.”

“Maybe,” she said lightly. She shrugged her shoulders, took a cigarette from her pink enamel case and lit it. “People have been known to go insane, waiting for weeks to be led to the electric chair.” She blew out a cloud of smoke and looked at him through it, her eyes narrowed. “And you know, I bet you’d never have come near me tonight except for that lucky accident of the confession—which you had nothing to do with.”

He tried to meet her eyes, failed, and sank down on the yellow brocade love seat, looking at the floor, wordless. Anna Marie stood for a moment, watching him. It was hard not to feel sorry for a man who seemed so anxious, so dejected—and so guilty.

Jesse Conway was middle-aged, well dressed, and dignified. His hair was gray, but it was still heavy, and carefully brushed. He had a handsome, deeply lined face, though the eyes were just a trifle bloodshot, and the lips twitched ever so little when they should have been in repose. A fine figure of a man, his friends said.

“Believe me,” he muttered, “believe me, Anna Marie, it was none of my doing. I couldn’t help it. I knew you were being framed.”

“And you helped them frame me,” she said without bitterness, almost gaily. “My own lawyer.”

“No,” he said, looking at the floor. “No, that isn’t true. But my hands were tied, and you know it. Why, you were convicted before I was even engaged as your lawyer. And even then”—he crumpled a handkerchief between his palms, looked away—“you had the wrong lawyer, that’s all.”

Anna Marie remembered the weeks she’d spent in the death cell and laughed harshly. “That’s no news to me.”

“You don’t understand,” he said dully. “That isn’t what I meant at all. There’s one lawyer who might have spared you this. He’s not afraid of anything or anybody. They say he’s as crooked as a worm in an apple, but nobody can buy him if he doesn’t want to be bought. At your trial the judge and the jury were fixed, but even with that he might have come up with something. I even thought”—he paused—“it’s a damned shame that”—paused again and finally said, looking up, “I mean

Comments (0)