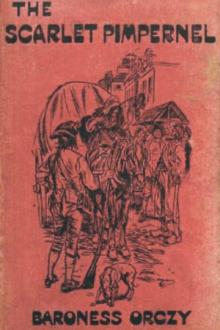

The Triumph of the Scarlet Pimpernel - Baroness Orczy (the little red hen read aloud .txt) 📗

- Author: Baroness Orczy

Book online «The Triumph of the Scarlet Pimpernel - Baroness Orczy (the little red hen read aloud .txt) 📗». Author Baroness Orczy

She stood for a moment, gazing mechanically on the retreating figure of the asthmatic giant. The next moment she heard her name spoken, and turned quickly with a little cry of joy.

“Régine!”

A young man was hurrying towards her, was soon by her side and took her hand.

“I have been waiting,” he said reproachfully, “for more than an hour.”

In the twilight his face appeared pinched and pale, with dark, deep-sunken eyes that told of a troubled soul and a consuming, inward fire. He wore cloth clothes that were very much the worse for wear, and boots that were down at heel. A battered tricorne hat was pushed back from his high forehead, exposing the veined temples with the line of brown hair, and the arched, intellectual brows that proclaimed the enthusiast rather than the man of action.

“I am sorry, Bertrand,” the girl said simply. “But I had to wait such a long time at Mother Théot’s, and—”

“But what were you doing now?” he queried with an impatient frown. “I saw you from a distance. You came out of yonder house, and then stood here like one bewildered. You did not hear when first I called.”

“I have had quite a funny adventure,” Régine explained; “and I am very tired. Sit down with me, Bertrand, for a moment. I’ll tell you all about it.”

A flat refusal hovered palpably on his lips.

“It is too late—” he began, and the frown of impatience deepened upon his brow. He tried to protest, but Régine did look very tired. Already, without waiting for his consent, she had turned into the little porch, and Bertrand perforce had to follow her.

The shades of evening now were fast gathering in, and the lengthened shadows stretched out away, right across the street. The last rays of the sinking sun still tinged the roofs and chimney pots opposite with a crimson hue. But here, in the hallowed little trysting-place, the kingdom of night had already established its sway. The darkness lent an air of solitude and of security to this tiny refuge, and Régine drew a happy little sigh as she walked deliberately to its farthermost recess and sat down on the wooden bench in it extreme and darkest angle.

Behind her, the heavy oaken door of the church was closed. The church itself, owning to the contumaciousness of its parish priest, had been desecrated by the ruthless hands of the Terrorists and left derelict, to fall into decay. The stone walls themselves appeared cut off from the world, as if ostracised. But between them Régine felt safe, and when Bertrand Moncrif somewhat reluctantly sat down beside her, she also felt almost happy.

“It is very late,” he murmured once more, ungraciously.

She was leaning her head against the wall, looked so pale, with eyes closed and bloodless lips, that the young man’s heart was suddenly filled with compunction.

“You are not ill, Régine?” he asked, more gently.

“No,” she replied, and smiled bravely up at him. “Only very tired and a little dizzy. The atmosphere in Catherine Théot’s rooms was stifling, and then when I came out—”

He took her hand, obviously making an effort to be patient and to be kind; and she, not noticing the effort or his absorption, began to tell him about her little adventure with the asthmatic giant.

“Such a droll creature,” she explained. “He would have frightened me but for that awful, churchyard cough.”

But the matter did not seem to interest Bertrand very much; and presently he took advantage of a pause in her narrative to ask abruptly:

“And Mother Théot, what had she to say?”

Régine gave a shudder.

“She foretells danger for us all,” she said.

“The old charlatan!” he retorted with a shrug of the shoulders. “As if everyone was not in danger these days!”

“She gave me a powder,” Régine went on simply, “which she thinks will calm Joséphine’s nerves.”

“And that is folly,” he broke in harshly. “We do not want Joséphine’s nerves to be calmed.”

But at his words, which in truth sounded almost cruel, Régine roused herself with a sudden air of authority.

“Bertrand,” she said firmly, “you are doing a great wrong by dragging the child into your schemes. Joséphine is too young to be used as a tool by a pack of thoughtless enthusiasts.”

A bitter, scornful laugh from Bertrand broke in on her vehemence.

“Thoughtless enthusiasts!” he exclaimed roughly. “Is that how you call us, Régine? My God! where is your loyalty, your devotion? Have you no faith, no aspirations? Do you no longer worship God or reverence your King?”

“In heaven’s name, Bertrand, take care!” she whispered hoarsely, looked about her as if the stone walls of the porch had ears and eyes fixed upon the man she loved.

“Take care!” he rejoined bitterly. “Yes! that is your creed now. Caution! Circumspection! You fear—”

“For you,” she broke in reproachfully; “for Joséphine; for maman; for Jacques—not for myself, God knows!”

“We must all take risks, Régine,” he retorted more composedly. “We must all risk our miserable lives in order to end this awful, revolting tyranny. We must have a wider outlook, think not only of ourselves, of those immediately round us, but of France, of humanity, of the entire world. The despotism of a bloodthirsty autocrat has made of the people of France a people of slaves, cringing, fearful, abject—swayed by his word, too cowardly now to rebel.”

“And what are you? My God!” she cried passionately. “You and your friends, my poor young sister, my foolish little brother? What are you, that you think you can stem the torrent of this stupendous Revolution? How think you that your feeble voices will be heard above the roar of a whole nation in the throws of misery and of shame?”

“It is the still small voice,” Bertrand replied, in the tone of a visionary, who sees mysteries and who dreams dreams, “that is heard by its persistence even above the fury of thousands in

Comments (0)