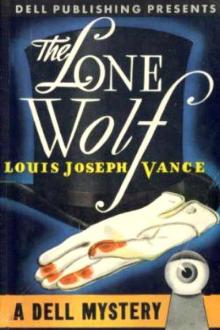

The Lone Wolf - Louis Joseph Vance (year 7 reading list txt) 📗

- Author: Louis Joseph Vance

- Performer: -

Book online «The Lone Wolf - Louis Joseph Vance (year 7 reading list txt) 📗». Author Louis Joseph Vance

something too damnably adventitious in the way she had nailed him,

back there in the corridor of Troyon’s. It was a bit too

coincidental—“a bit thick!”—like that specious yarn of somnambulism

she had told to excuse her presence in his room. Come to examine it,

that excuse had been far too clumsy to hoodwink any but a man

bewitched by beauty in distress.

Who was she, anyway? And what her interest in him? What had she been

after in his room?—this American girl making a first visit to Paris

in company with her venerable ruin of a parent? Who, for that matter,

was Bannon? If her story of sleepwalking were untrue, then Bannon

must have been at the bottom of her essay in espionage—Bannon, the

intimate of De Morbihan, and an American even as the murderer of poor

Roddy was an American!

Was this singularly casual encounter, then, but a cloak for further

surveillance? Had he in his haste and desperation simply played into

her hands, when he burdened himself with the care of her?

But it seemed absurd; to think that she… a girl like her, whose every

word and gesture was eloquent of gentle birth and training…!

Yet—what had she wanted in his room? Somnambulists are sincere

indeed in the indulgence of their failing when they time their

expeditions so opportunely—and arm themselves with keys to fit strange

doors. Come to think of it, he had been rather willfully blind to that

flaw in her excuse…. Again, why should she be up and dressed and so

madly bent on leaving Troyon’s at half-past four in the morning? Why

couldn’t she wait for daylight at least? What errand, reasonable duty

or design could have roused her out into the night and the storm at

that weird hour? He wondered!

And momentarily he grew more jealously heedful of her, critical of

every nuance in her bearing. The least trace of added pressure on his

arm, the most subtle suggestion that she wasn’t entirely indifferent to

him or regarded him in any way other than as the chance-found comrade

of an hour of trouble, would have served to fix his suspicions. For

such, he told himself, would be the first thought of one bent on

beguiling—to lead him on by some intimation, the more tenuous and

elusive the more provocative, that she found his person not altogether

objectionable.

But he failed to detect anything of this nature in her manner.

So, what was one to think? That she was mental enough to appreciate how

ruinous to her design would be any such advances? …

In such perplexity he brought her to the end of the alley and there

pulled up for a look round before venturing out into the narrow, dark,

and deserted side street that then presented itself.

At this the girl gently disengaged her hand and drew away a pace or two;

and when Lanyard had satisfied himself that there were no Apaches in the

offing, he turned to see her standing there, just within the mouth of

the alley, in a pose of blank indecision.

Conscious of his regard, she turned to his inspection a face touched

with a fugitive, uncertain smile.

“Where are we?” she asked.

He named the street; and she shook her head. “That doesn’t mean much to

me,” she confessed; “I’m so strange to Paris, I know only a few of the

principal streets. Where is the boulevard St. Germain?”

Lanyard indicated the direction: “Two blocks that way.”

“Thank you.” She advanced a step or two, but paused again. “Do you

know, possibly, just where I could find a taxicab?”

“I’m afraid you won’t find any hereabouts at this hour,” he replied. “A

fiacre, perhaps—with luck: I doubt if there’s one disengaged nearer

than Montmartre, where business is apt to be more brisk.”

“Oh!” she cried in dismay. “I hadn’t thought of that….

I thought Paris never went to sleep!”

“Only about three hours earlier than most of the world’s capitals….

But perhaps I can advise you—”

“If you would be so kind! Only, I don’t like to be a nuisance—”

He smiled deceptively: “Don’t worry about that. Where do you wish to

go?”

“To the Gare du Nord.”

That made him open his eyes. “The Gare du Nord!” he echoed. “But—I beg

your pardon—”

“I wish to take the first train for London,” the girl informed him

calmly.

“You’ll have a while to wait,” Lanyard suggested. “The first train

leaves about half-past eight, and it’s now not more than five.”

“That can’t be helped. I can wait in the station.”

He shrugged: that was her own look-out—if she were sincere in

asserting that she meant to leave Paris; something which he took the

liberty of doubting.

“You can reach it by the M�tro,” he suggested—“the Underground, you

know; there’s a station handy—St. Germain des Pr�s. If you like, I’ll

show you the way.”

Her relief seemed so genuine, he could have almost believed in it. And

yet—!

“I shall be very grateful,” she murmured.

He took that for whatever worth it might assay, and quietly fell into

place beside her; and in a mutual silence—perhaps largely due to her

intuitive sense of his bias—they gained the boulevard St. Germain. But

here, even as they emerged from the side street, that happened which

again upset Lanyard’s plans: a belated fiacre hove up out of the mist

and ranged alongside, its driver loudly soliciting patronage.

Beneath his breath Lanyard cursed the man liberally, nothing could have

been more inopportune; he needed that uncouth conveyance for his own

purposes, and if only it had waited until he had piloted the girl to

the station of the M�tropolitain, he might have had it. Now he must

either yield the cab to the girl or—share it with her…. But why not?

He could readily drop out at his destination, and bid the driver

continue to the Gare du Nord; and the M�tro was neither quick nor

direct enough for his design—which included getting under cover well

before daybreak.

Somewhat sulkily, then, if without betraying his temper, he signalled

the cocher, opened the door, and handed the girl in.

“If you don’t mind dropping me en route…”

“I shall be very glad,” she said … “anything to repay, even in part,

the courtesy you’ve shown me!”

“Oh, please don’t fret about that….”

He gave the driver precise directions, climbed in, and settled himself

beside the girl. The whip cracked, the horse sighed, the driver swore;

the aged fiacre groaned, stirred with reluctance, crawled wearily off

through the thickening drizzle.

Within its body a common restraint held silence like a wall between the

two.

The girl sat with face averted, reading through the window what corner

signs they passed: rue Bonaparte, rue Jacob, rue des Saints P�res, Quai

Malquais, Pont du Carrousel; recognizing at least one landmark in the

gloomy arches of the Louvre; vaguely wondering at the inept French taste

in nomenclature which had christened that vast, louring, echoing

quadrangle the place du Carrousel, unliveliest of public places in her

strange Parisian experience.

And in his turn, Lanyard reviewed those well-remembered ways in vast

weariness of spirit—disgusted with himself in consciousness that the

girl had somehow divined his distrust….

“The Lone Wolf, eh?” he mused bitterly. “Rather, the Cornered Rat—if

people only knew! Better still, the Errant—no!—the Arrant Ass!”

They were skirting the Palais Royal when suddenly she turned to him in

an impulsive attempt at self-justification.

“What must you be thinking of me, Mr. Lanyard?”

He was startled: “I? Oh, don’t consider me, please. It doesn’t matter

what I think—does it?”

“But you’ve been so kind; I feel I owe you at least some explanation—”

“Oh, as for that,” he countered cheerfully, “I’ve got a pretty definite

notion you’re running away from your father.”

“Yes. I couldn’t stand it any longer—”

She caught herself up in full voice, as though tempted but afraid to

say more. He waited briefly before offering encouragement.

“I hope I haven’t seemed impertinent….”

“No, no!”

Than this impatient negative his pause of invitation evoked no other

recognition. She had subsided into her reserve, but—he fancied—not

altogether willingly.

Was it, then, possible that he had misjudged her?

“You’ve friends in London, no doubt?” he ventured.

“No—none.”

“But—”

“I shall manage very well. I shan’t be there more than a day or

two—till the next steamer sails.”

“I see.” There had sounded in her tone a finality which signified

desire to drop the subject. None the less, he pursued mischievously:

“Permit me to wish you bon voyage, Miss Bannon… and to express my

regret that circumstances have conspired to change your plans.”

She was still eyeing him askance, dubiously, as if weighing the

question of his acquaintance with her plans, when the fiacre lumbered

from the rue Vivienne into the place de la Bourse, rounded that

frowning pile, and drew up on its north side before the blue lights of

the all-night telegraph bureau.

“With permission,” Lanyard said, unlatching the door, “I’ll stop off

here. But I’ll direct the cocher very carefully to the Gare du Nord.

Please don’t even tip him—that’s my affair. No—not another word of

thanks; to have been permitted to be of service—it is a unique

pleasure, Miss Bannon. And so, good night!”

With an effect that seemed little less than timid, the girl offered her

hand.

“Thank you, Mr. Lanyard,” she said in an unsteady voice. “I am sorry—”

But she didn’t say what it was she regretted; and Lanyard, standing

with bared head in the driving mist, touched her fingers coolly,

repeated his farewells, and gave the driver both money and

instructions, and watched the cab lurch away before he approached the

telegraph bureau….

But the enigma of the girl so deeply intrigued his imagination that it

was only with difficulty that he concocted a non-committal telegram to

Roddy’s friend in the Prefecture—that imposing personage who had

watched with the man from Scotland Yard at the platform gates in the

Gare du Nord.

It was couched in English, when eventually composed and submitted to

the telegraph clerk with a fervent if inaudible prayer that he might be

ignorant of the tongue.

_”Come at once to my room at Troyon’s. Enter via adjoining room

prepared for immediate action on important development. Urgent.

Roddy.“_

Whether or not this were Greek to the man behind the wicket, it was

accepted with complete indifference—or, rather, with an interest that

apparently evaporated on receipt of the fees. Lanyard couldn’t see that

the clerk favoured him with as much as a curious glance before he

turned away to lose himself, to bury his identity finally and forever

under the incognito of the Lone Wolf.

He couldn’t have rested without taking that one step to compass the

arrest of the American assassin; now with luck and prompt action on the

part of the Pr�fecture, he felt sure Roddy would be avenged by Monsieur

de Paris…. But it was very well that there should exist no clue

whereby the author of that mysterious telegram might be traced….

It was, then, not an ill-pleased Lanyard who slipped oft into the night

and the rain; but his exasperation was elaborate when the first object

that met his gaze was that wretched fiacre, back in place before the

door, Lucia Bannon leaning from its lowered window, the cocher on his

box brandishing an importunate whip at the adventurer.

He barely escaped choking on suppressed profanity; and for two sous

would have swung on his heel and

Comments (0)