The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling - Henry Fielding (top ten ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Henry Fielding

Book online «The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling - Henry Fielding (top ten ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Henry Fielding

This particular we thought ourselves obliged to mention, as it may account for our hero’s temporary neglect of his fair companion, who eat but very little, and was indeed employed in considerations of a very different nature, which passed unobserved by Jones, till he had entirely satisfied that appetite which a fast of twenty-four hours had procured him; but his dinner was no sooner ended than his attention to other matters revived; with these matters therefore we shall now proceed to acquaint the reader.

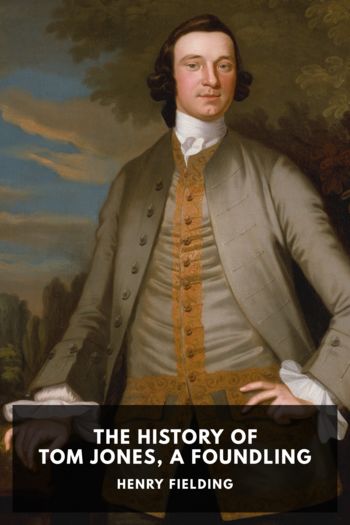

Mr. Jones, of whose personal accomplishments we have hitherto said very little, was, in reality, one of the handsomest young fellows in the world. His face, besides being the picture of health, had in it the most apparent marks of sweetness and good-nature. These qualities were indeed so characteristical in his countenance, that, while the spirit and sensibility in his eyes, though they must have been perceived by an accurate observer, might have escaped the notice of the less discerning, so strongly was this good-nature painted in his look, that it was remarked by almost everyone who saw him.

It was, perhaps, as much owing to this as to a very fine complexion that his face had a delicacy in it almost inexpressible, and which might have given him an air rather too effeminate, had it not been joined to a most masculine person and mien: which latter had as much in them of the Hercules as the former had of the Adonis. He was besides active, genteel, gay, and good-humoured; and had a flow of animal spirits which enlivened every conversation where he was present.

When the reader hath duly reflected on these many charms which all centered in our hero, and considers at the same time the fresh obligations which Mrs. Waters had to him, it will be a mark more of prudery than candour to entertain a bad opinion of her because she conceived a very good opinion of him.

But, whatever censures may be passed upon her, it is my business to relate matters of fact with veracity. Mrs. Waters had, in truth, not only a good opinion of our hero, but a very great affection for him. To speak out boldly at once, she was in love, according to the present universally-received sense of that phrase, by which love is applied indiscriminately to the desirable objects of all our passions, appetites, and senses, and is understood to be that preference which we give to one kind of food rather than to another.

But though the love to these several objects may possibly be one and the same in all cases, its operations however must be allowed to be different; for, how much soever we may be in love with an excellent sirloin of beef, or bottle of Burgundy; with a damask rose, or Cremona fiddle; yet do we never smile, nor ogle, nor dress, nor flatter, nor endeavour by any other arts or tricks to gain the affection of the said beef, etc. Sigh indeed we sometimes may; but it is generally in the absence, not in the presence, of the beloved object. For otherwise we might possibly complain of their ingratitude and deafness, with the same reason as Pasiphae doth of her bull, whom she endeavoured to engage by all the coquetry practised with good success in the drawing-room on the much more sensible as well as tender hearts of the fine gentlemen there.

The contrary happens in that love which operates between persons of the same species, but of different sexes. Here we are no sooner in love than it becomes our principal care to engage the affection of the object beloved. For what other purpose indeed are our youth instructed in all the arts of rendering themselves agreeable? If it was not with a view to this love, I question whether any of those trades which deal in setting off and adorning the human person would procure a livelihood. Nay, those great polishers of our manners, who are by some thought to teach what principally distinguishes us from the brute creation, even dancing-masters themselves, might possibly find no place in society. In short, all the graces which young ladies and young gentlemen too learn from others, and the many improvements which, by the help of a looking-glass, they add of their own, are in reality those very spicula et faces amoris so often mentioned by Ovid; or, as they are sometimes called in our own language, the whole artillery of love.

Now Mrs. Waters and our hero had no sooner sat down together than the former began to play this artillery upon the latter. But here, as we are about to attempt a description hitherto unassayed either in prose or verse, we think proper to invoke the assistance of certain aërial beings, who will, we doubt not, come kindly to our aid on this occasion.

“Say then, ye Graces! you that inhabit the heavenly mansions of Seraphina’s countenance; for you are truly divine, are always in her presence, and well know all the arts of charming; say, what were the weapons now used to captivate the heart of Mr. Jones.”

“First, from two lovely blue eyes, whose bright orbs flashed lightning at their discharge, flew forth two pointed ogles; but, happily for our hero, hit only a vast piece of beef which he was then conveying into his plate, and harmless spent their force. The fair warrior perceived their miscarriage, and immediately from her fair bosom drew forth a deadly sigh. A sigh which none could have heard unmoved, and which was sufficient at once to have swept off a dozen beaus; so soft, so sweet, so tender, that the insinuating air must have found its subtle way to the heart of our hero, had it not luckily been driven from his ears by the coarse bubbling of some bottled ale, which at that time he was pouring forth.

Comments (0)