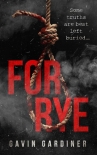

For Rye by Gavin Gardiner (books for 10th graders txt) 📗

- Author: Gavin Gardiner

Book online «For Rye by Gavin Gardiner (books for 10th graders txt) 📗». Author Gavin Gardiner

‘No, you don’t want to be here at all,’ she’d spoken into Samson’s pitiful face. ‘Let’s get you out of here.’

And so here she is, in a woodland clearing some half hour’s walk past the church and through the fields. With the firs, pines, and cedars towering on all sides, rippling in the breeze, the crippled dog lies on some flattened undergrowth with the girl standing over him, foot poised.

She doesn’t want to put her foot through his skull, but she knows she has to.

It’s not the jealousy, she keeps telling herself. This isn’t about the jealousy. It’s about putting Samson out of his misery, since she’s the only one besides Mr Milton who seems to care what happens to him. It doesn’t matter how much trouble she gets in, or what Father will do. She’ll tell him Samson escaped again when she let him out into the back garden. Actually, she won’t bother. She’ll be punished no matter what she says. And besides, the thing can barely walk, let alone ‘escape’. No, she’ll do it and face whatever she’s made to face. One quick stomp (he probably won’t even feel it) and the pain will be over. She’ll have saved a living creature a torturous existence.

It isn’t about the jealousy.

The sun casts distorted shadows of criss-crossing branches and foliage from the forest ceiling. The girl looks around the clearing, spotting a squirrel dashing up a tree, then a magpie hopping from a fallen trunk. The tapestry of sound is soothing. Tweeting and rustling, chirping and stirring, distant squawking, and the gentle afternoon breeze flowing amongst the flora: it all moves through her with a calming influence. She lowers her gaze to the quivering creature beneath her poised foot.

Samson’s one good eye looks up at her.

One…

Two…

Three…

The mongrel sighs, then lowers his head to the moss.

Nope, not happening. The girl admits defeat and eventually heaves the thing back to the house, cursing herself for thinking she’d ever be able to follow through with such a deed. Samson’s suffering will just have to continue. It’s because she’s just a little girl – a sweet, innocent little girl. That’s why she couldn’t do it, not because of the terrible vision in the moments before she lowered her foot in resignation, the vision of her father’s twitching fist.

Little girls aren’t meant to cave in skulls, that’s all.

Having returned to the back garden, the girl lowers Samson to the grass and closes the gate. She steps up to the back door which leads into the kitchen and slots the key into the lock, shaking her head at the thought of having lost an entire afternoon of reading. She opens the door, thinking about how many chapters of Doctor Zhivago she could have torn through in the time it had taken to—

‘Father?’

‘Step inside, Renata.’

The girl places the key in her father’s outstretched, quivering hand, then glimpses the walk-in larder door lying ajar behind him. It’s never left ajar. She lowers her gaze as he steps to the window and looks out at Samson curled on the grass.

‘Couldn’t do it, could you?’ he says. ‘I had your punishment all ready, too.’ He glances through the open kitchen door to the bookcase in the lounge.

Not the Bible, please. Not again.

‘I’m going back to the hospital. Your mother’s due any day now.’

‘Can I come, Father?’

Thomas Wakefield’s eyes deepen, his face reddening as if his daughter has spoken some terrible insult. She takes a step back as his fists tighten and his chest rises. Suddenly he lashes like a cobra, grabbing her by the wrist – that agonising grip – and drags her to the larder. He swings the door open and flings the girl inside, where she trips and lands in a heap before him.

‘Trust me, child,’ he growls down at her, ‘this is a mercy.’

He pulls her up then drives her into a wooden chair in the middle of the larder. Her eyes dart around at the towers of tinned foods, mountains of branded packets, and walls of Tupperware, indifferent and uncaring. She realises in a panic that the chair is fixed, unmoving. Looking below she sees it’s bolted to the floor.

Help me Mother I’m not like you I don’t have any flood in me I’m not strong I can’t do it I can’t I—

‘I’ve tried so hard with you,’ he says, straightening out four lengths of rope in his hands. The girl grips the arms of the chair, face white with terror. ‘No matter what I teach you, no matter how many hours I make you study the holy book, you just don’t learn, do you?’

She stands up then is pushed back down so hard that all the air is knocked from her lungs. Through her choking for air, she feels those clamp-like hands on one of her wrists, followed by the tightening of rope. Her other hand, frantically wiping away the tears obscuring her vision, is wrenched down and also tied in place. She thrashes her legs as her father drops to his knees, ignoring the kicking, and ties her ankles into position. The man takes a step back as she lashes and writhes against the ropes.

‘I HATE YOU,’ the girl screams, face red with fury. ‘I’LL KILL YOU.’

Father and daughter turn to stone, he in the doorway, she bound in the chair. They stare into one another’s eyes for a moment that transcends fear or anger, instead infused with some kind of tension, a promise of possibility. Something unfolds inside both of their minds – part revelation, part reminder – that in this world anything is possible.

Thomas Wakefield breaks from his daughter’s stare and, in a moment the girl will never forget, drops his

Comments (0)