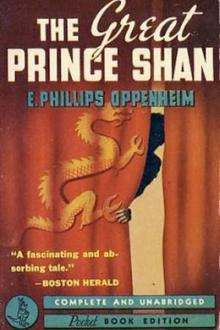

The Great Prince Shan - E. Phillips Oppenheim (top books of all time .txt) 📗

- Author: E. Phillips Oppenheim

- Performer: -

Book online «The Great Prince Shan - E. Phillips Oppenheim (top books of all time .txt) 📗». Author E. Phillips Oppenheim

"It depends upon Prince Shan," she replied. "The terms were Immelan's, but the method was his."

"Do you believe," he asked a little abruptly, "that the attempt on Prince Shan's life last night was made by Immelan?"

There was a touch, perhaps, of her Muscovite ancestry in the cool indifference with which she considered the matter.

"I should think it most likely," she decided. "Prince Shan never changes his mind, and I believe that he has decided against Immelan's scheme. Immelan's only chance would be in Prince Shan's successor."

"Why is China so necessary?" Nigel asked.

She turned and smiled at her companion.

"Alas!" she sighed, "we have reached an impasse. The great English diplomat asks too many questions of the simple Russian girl."

"It is unfortunate," he replied, in the same vein, "because I feel like asking more."

"As, for example?"

"Whether you would be content to live for the rest of your life in any other country except Russia."

"A woman is content to live anywhere, under certain circumstances," she murmured.

Karschoff, discreetly announced, entered the room with flamboyant ease.

"It is well to be young!" he exclaimed, as he bent over Naida's fingers. "You look, my far-away but much beloved cousin, as though you had slept peacefully through the night and spent the morning in this soft, sunlit air, with perhaps, if one might suggest such a thing, an hour at a Bond Street beauty parlour. Here am I with crow's-feet under my eyes and ghosts walking by my side. Yet none the less," he added, as the door opened and Maggie appeared, "looking forward to my luncheon and to hear all the news."

"There is no news," Naida declared, as the butler announced the service of the meal. "We have reached the far end of the ways. The next disclosures, if ever they are made, will come from others. At luncheon we are going to talk of the English country, the seaside, the meadows, and the quiet places. The time arrives when I weary, weary, of the brazen ticking of the clock of fate."

"I shall tell you," Nigel declared, "of a small country house I have in Devonshire. There are rough grounds stretching down to the sea and crawling up to the moors behind. My grandfather built it when he was Chancellor of England, or rather he added to an old farmhouse. He called it the House of Peace."

"My father built a house very much in the same spirit," Naida told them. "He called it after an old Turkish inscription, engraven on the front of a villa in Stamboul—'The House of Thought and Flowers.'"

Maggie smiled across the table approvingly.

"I like the conversation," she said. "Naida and I are, after all, women and sentimentalists. We claim a respite, an armistice—call it what you will. Prince Karschoff, won't you tell me of the most beautiful house you ever dwelt in?"

"Always the house I am hoping to end my days in," he answered. "But let me tell you about a villa I had in Cannes, fifteen years ago. People used to speak of it as one of the world's treasures."

When the two men were seated alone over their coffee, Nigel passed Chalmers' note and the enclosure across to his companion.

"You remember I told you about Chalmers' friend, Jesson, the secret service man who came over to us?" he said. "Chalmers has just sent me round this."

Karschoff nodded and studied the message through his great horn-rimmed eyeglass.

"I thought that he was going to Russia for you," he said.

"So he did. He must have gone on from there."

"And the message comes from Southern China," Prince Karschoff reflected.

Nigel was deep in thought. China, Russia, Germany! Prince Shan in England, negotiating with Immelan! And behind, sinister, menacing, mysterious—Japan!

"Supposing," he propounded at last, "there really does exist a secret treaty between China and Japan?"

"If there is," Prince Karschoff observed, "one can easily understand what Immelan has been at. Prince Shan can command the whole of Asia. I know they are afraid of something of the sort in the States. An American who was in the club yesterday told us they had spent over a hundred millions on their west coast fortifications in the last two years."

"One can understand, too, in that case," Nigel continued, "why Japan left the League of Nations. That stunt of hers about being outside the sphere of possible misunderstandings never sounded honest."

"It was unfortunate," Prince Karschoff said, "that America was dominated for those few months by an honest but impractical idealist. He had the germ of an idea, but he thrust it on the world before even his own country was ready for it. In time the nations would certainly have elaborated something more workable."

"You cannot keep a full-blooded man from clenching his fist if he's insulted," Nigel pointed out, "and nations march along the same lines as individuals. Its existence has never for a single moment weakened Germany's hatred of England, and the stronger she grows, the more she flaunts its conditions. France guards her frontiers, night and day, with an army ten times larger than she is allowed. Russia has become the country of mysteries, with something up her sleeve, beyond a doubt, and there are cities in modern China into which no European dare penetrate. Japan quite frankly maintains an immense army, the United States is silently following suit—and God help us all if a war does come!"

"You are right," Karschoff assented gloomily. "The last glamour of romance has gone from fighting. There were remnants of it in the last war, especially in Palestine and Egypt and when we first overran Austria. To-day, science would settle the whole affair. The war would be won in the laboratory, the engine room and the workshop. I doubt whether any battleship could keep afloat for a week, and as to the fighting in the air, if a hundred airships were in action, I do not suppose that one of them would escape. Then they say that France has a gun which could carry a shell from Amiens to London, and more mysterious than all, China has something up her sleeve which no one has even a glimmering of."

"Except Jesson," Nigel muttered.

"And Jesson's gleam of knowledge, or suspicion," Prince Karschoff remarked, "seems to have brought him to the end of his days. Can anything be done with Prince Shan about him, do you think?"

"Only indirectly, I am afraid," Nigel replied. "Maggie is seeing him this afternoon. As a matter of fact, I believe she telephoned to him before luncheon, but I haven't heard anything yet. When a man goes out on that sort of a job, he burns his boats. And Jesson isn't the first who has turned eastwards, during the last few months. I heard only yesterday that France has lost three of her best men in China—one who went as a missionary and two as merchants. They've just disappeared without a word of explanation."

The telephone extension bell rang. Nigel walked over to the sideboard and took down the receiver.

"Is that Lord Dorminster?" a man's voice asked.

"Speaking," Nigel replied.

"I am David Franklin, private secretary to Mr. Mervin Brown," the voice continued. "Mr. Mervin Brown would be exceedingly obliged if you would come round to Downing Street to see him at once."

"I will be there in ten minutes," Nigel promised.

He laid down the receiver and turned to Karschoff.

"The Prime Minister," he explained.

"What does he want you for?"

"I think," Nigel replied, "that the trouble cloud is about to burst."

Mr. Mervin Brown on this occasion did not beat about the bush. His old air of confident, almost smug self-satisfaction, had vanished. He received Nigel with a new deference in his manner, without any further sign of that good-natured tolerance accorded by a busy man to a kindly crank.

"Lord Dorminster," he began, "I have sent for you to renew a conversation we had some little time since. I will be quite frank with you. Certain circumstances have come to my notice which lead me to believe that there may be more truth in some of the arguments you brought forward than I was willing at the time to believe."

"I must confess that I am relieved to hear you say so," Nigel replied. "All the information which I have points to a crisis very near at hand."

The Prime Minister leaned a little across the table.

"The immediate reason for my sending for you," he explained, "is this. My friend the American Ambassador has just sent me a copy of a wireless dispatch which he has received from China from one of their former agents. The report seems to have been sent to him for safety, but the sender of it, of whose probity, by the by, the American Ambassador pledges himself, appears to have been sent to China by you."

"Jesson!" Nigel exclaimed. "I have heard of this already, sir, from a friend in the American Embassy."

"The dispatch," Mr. Mervin Brown went on, "is in some respects a little vague, but it is, on the other hand, I frankly admit, disturbing. It gives specific details as to definite military preparations on the part of China and Russia, associated, presumably, with a third Power whose name you will forgive my not mentioning. These preparations appear to have been brought almost to completion in the strictest secrecy, but the headquarters of the whole thing, very much to my surprise, I must confess, seems to be in southern China."

"In that case," Nigel pointed out, "if you will permit me to make a suggestion, sir, you have a very simple course open to you."

"Well?"

"Send for Prince Shan."

"Prince Shan," the Prime Minister replied, with knitted brows, "is not over in this country officially. He has begged to be excused from accepting or returning any diplomatic courtesies."

"Nevertheless," Nigel persisted, "I should send for Prince Shan. If it had not been," he went on slowly, "for the complete abolition of our secret service system, you would probably have been informed before now that Prince Shan has been having continual conferences in this country with one of the most dangerous men who ever set foot on these shores—Oscar Immelan."

"Immelan has no official position in this country," the Prime Minister objected.

"A fact which makes him none the less dangerous," Nigel insisted. "He is one of those free lances of diplomacy who have sprung up during the last ten or fifteen years, the product of that spurious wave of altruism which is responsible for the League of Nations. Immelan was one of the first to see how his country might benefit by the new régime. It is he who has been pulling the strings in Russia and China, and, I fear, another country."

"What I want to arrive at," Mr. Mervin Brown said, a little impatiently, "is something definite."

"Let me put it my own way," Nigel begged. "A very large section of our present-day politicians—you, if I may say so, amongst them, Mr. Mervin Brown—have believed this country safe against any military dangers, because of the connections existing between your unions of working men and similar bodies in Germany. This is a great fallacy for two reasons: first because Germany has always intended to have some one else pull the chestnuts out of the fire for her, and second because we cannot internationalise labour. English and German workmen may come together on matters affecting their craft and the conditions of their labour, but at heart one remains a German and one an Englishman, with separate interests and a separate outlook."

"Well, at the end of it all," Mr. Mervin Brown said, "the bogey is war. What sort of a war? An invasion of England is just as impossible to-day as it was twenty years ago."

Nigel nodded.

"I cannot answer your question," he admitted. "I was looking to Jesson's report to give us an idea as to that."

"You shall see it to-morrow," Mr. Mervin Brown promised. "It is round at the War Office at the present moment."

"Without seeing it," Nigel went on, "I expect I can tell you one startling feature

Comments (0)