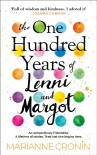

The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot by Marianne Cronin (e reader books txt) 📗

- Author: Marianne Cronin

Book online «The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot by Marianne Cronin (e reader books txt) 📗». Author Marianne Cronin

Whatever grey absence had been dancing in my eyes grew wider until it had taken everything. Where Davey’s sweet, sleeping face should have been was nothing. I closed my eyes and made an appeal to whatever gods in the universe were listening.

I stroked Davey’s head so that he could be sure I was still there, and so that I could be sure he was still there. I rested a hand on his tiny chest and felt the gentle rise and fall of his breathing. How could there be something wrong with his heart when I could feel it beating stronger than my own? I reluctantly closed my eyes. I let the tears spill onto my arm and my sleeve, and I stroked his hair and I kissed his cheek and I told him more stories about the world, about jungles and animals and stars.

When I woke up, the migraine was gone.

Davey was gone too.

Lenni

‘LENNI, CAN YOU hear me?’

‘Lenni, talk to us, sweetheart.’

‘Lenni?’

The bed was laid flat beneath me; there were more voices.

‘It’s okay, Lenni, we’re here. Just stay calm.’

PART TWO

Lenni

WHENEVER I GO under general anaesthetic, I have the most vivid dreams. They are so vivid that in the past I have been accused of inventing them. I remember telling another girl in a different hospital in a different country about my dream, and she didn’t believe it. This dream, though, is incredible and it feels like it lasts for days and days. There is an octopus and we are the fiercest of friends. He is purple, and everything is bright and extraordinary. And I can hear the most wonderful music.

Margot and the Diary

Hello, Lenni, it’s Margot.

I’ve missed you.

Your red-haired nurse came into my ward yesterday. She said you’d asked, before they took you in for the operation, that I be given your diary. She said you write in it all the time and she suspects she might be in it. She said you wanted me to write you something.

I’m honoured you trust me with it, but you should know I’ve only accepted this book as a loan. If this is being bequeathed to me then I want no part of it, young lady.

You’ll take this surgery in your stride, I know it. Nothing scares you. I’m quite the opposite.

But here is a story for you to read when you wake up:

This week in the Rose Room, I painted the first place I lived that I really, truly loved. It was dirty and crooked. Like all the best characters.

The painting itself is fair. I know my old art teacher at school would have said that the perspective isn’t quite right, and the roof gives the impression of slanting backwards, but I’m happy with it nonetheless. The version of me that lives in my memory, the version of me that lives in that tiny flat, is a lot more like you than she is like me.

It starts, like all of my stories so far, in Scotland.

Glasgow to London, February 1959

Margot Docherty is Twenty-Eight Years Old

By the time I was twenty-eight, my father was the only one left. My mother had passed when I was twenty-six. And it had felt like I’d been orphaned when she went. The shellshock – they call it something else now – had eroded my father until he wouldn’t even allow me to sit with him. But sit I did, when the call came. He was already dead, but I sat beside him in the hospital and I memorized his face. I whispered an apology and a good luck wish for the journey, and I felt a severing. I was looking at the final thread on my tightrope, the choking embers of my only candle, the last of the lifeboats. And he was gone – snapped, extinguished, sailed away.

It was sad, but it was also freeing. I was no longer anybody’s. A childless mother and a husbandless wife, a parentless daughter with a small inheritance and no fixed address.

I could go anywhere. I realized I was free to begin again, and I didn’t lose that kernel of hope until I disembarked onto the dirty platform at Euston Station, determined that I would find my husband. The only person left.

I started with the police. It was very early in the morning; I had slept on the train but I felt dazed. My teeth had layers of fuzz when I ran my tongue along them, which, now I had felt the fuzz, I couldn’t stop doing. I’d eaten half a packet of Polo mints, but my mouth was still stale.

As I came out of the station into the light, seeing the rows of cars and red buses, the people pushing past one another on their way to work, it felt as though the suitcases in my hands were the only things tethering me to the ground.

I asked a hassled man in a hat for directions to the nearest police station, and after getting lost along several identical streets, I found it. And in I went, not letting myself stop for even a moment for fear that I might turn back.

There was a secretary at a desk and a row of stained chairs. I’d been rehearsing what I would say in my head when I was on the train.

Comments (0)