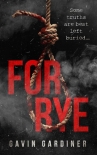

For Rye by Gavin Gardiner (books for 10th graders txt) 📗

- Author: Gavin Gardiner

Book online «For Rye by Gavin Gardiner (books for 10th graders txt) 📗». Author Gavin Gardiner

He points through the open door of the kitchen to the bucket and spade. ‘Wolms,’ he says.

‘No worms,’ the girl replies. ‘No digging tonight. You’re staying in.’

The boy lowers his hand. To her relief, he shuffles over to an abandoned toy fire engine and begins rolling it back and forth on the carpet by the fireplace.

An hour passes. The girl sets her pencil down and rises from the chair, walking to her bedroom window. The summer’s evening has turned to night. Her eyes follow the country roads that outline each of the surrounding fields. In the distance, the church. By the church, her clock tower. Everywhere else, an endless patchwork of fields.

She descends the staircase and looks into the living room.

The boy is gone.

‘Noah?’

No sound, no sign.

She returns upstairs and opens his bedroom door, cartoon bears and elephants chuckling in her face.

The boy is gone.

She runs back downstairs and swings open the dining room door: the boy is gone. Even the closet under the stairs: the boy is gone. Back to the living room: the boy is gone. The kitchen: the bucket and spade are gone.

Wolms.

Damn it.

For a moment, her mind’s eye is filled with the face of her father discovering his daughter’s allowing of Noah to go into the fields to play at night. ‘Lenata let me. Lenata said I could go, Daddy.’ She can hear it now. ‘I was scaled, Daddy. It was so scaly. Lenata said I could go, Daddy.’

Damn him.

She opens the back door into the empty garden.

Gone.

She steps into the night and looks out over the low-cut hedge across a sea of grass, the narrow country roads intersecting as they trace the perimeter of each field. He could have ended up in any of them in the hour since she last saw him. She would never be able to get round the fields fast enough to find the boy before her parents returned, and he knows it. The boy knows it. He knows she doesn’t have time to find him. He knows their father will hold her responsible. He knows she knows.

Hatred floods her veins.

Suddenly her mind’s eye turns from the future to the past, to the driving lessons.

Unbelieving of what her mind is telling her body to do, she walks across the living room and into the hall. On a hook by the front door are the keys to the Cortina. She takes them.

It’s dangerous, no question. Aside from wrapping the thing around a tree, as little as a scratch would be enough to push her father into a whole new realm of rage. She steps outside and looks at the car.

It’s covered in scratches.

They etch like roadmaps over the doors, the bonnet, the fenders, even the windows. It’s like an autopsy, metal and glass veins exposed to the cool summer air. She can see what happened as if it’s happening right now: the boy running around the car, scraping the spade across its paintwork, giggling that machine gun giggle.

‘Ee-ee-eeee!’

However this plays out, it won’t be in her favour. Could she draw attention to the scrape marks in the spade as proof of the boy’s guilt?

No, the girl used the spade to set him up.

Could she hide in her room, feign ignorance, and lay the act of vandalism, as well as his wandering into the night, upon him?

No, their little cherub would never do that.

Could she follow through with her original plan, use the car to find the boy, return him, and deal ‘only’ with the repercussions of the scratches? Damage limitation. The roads would be dry. The car wouldn’t get dirtied. There’d be no evidence of its outing into the night, only the scratches. Who knows, maybe they would believe her? She may survive the vandalism enquiry. A missing Noah she would not.

She clenches her fist around the keys and stares at the gleaming Ford Cortina, her father’s pride and joy.

Damn it.

She’s jostled as the car hits a pothole. She yanks the wheel to straighten the vehicle, watching the road for alignment. Keeping a steady speed (‘ABC: accelerator, brake, clutch, Rennie.’) she rolls the Ford along the track (‘Mirror, signal, manoeuvre, Rennie.’) while squinting out the side windows for any sign of her brother.

Moonlight blankets the swaying grass. Trees tremble in the distance. The night is quivering in apprehension. She skids the car to a halt as she spots something in a rippling pasture. Just a scarecrow. She eases the vehicle back into motion.

She hears rain pattering on the roof; tapping, as if her father’s incessantly tapping finger had been multiplied into an army of drumming digits sent to taunt her. She prays this sudden summer downpour will delay his return, not hasten it. Soon, the rain becomes bullets firing through the headlights. She turns left at an intersection between fields, cringing as a puddle splashes onto the side of the car.

The Cortina gains speed as she presses the tip of her outstretched foot into the accelerator. The wheel feels as heavy as a manhole cover, the car cumbersome, but the seventeen-year-old maintains control. She has lots of ground to cover. She can handle this thing. She presses harder.

It occurs to her that, since the brat was wanting to dig for worms with that stupid bucket and spade, he’d probably be hunkered down in the mud out of her line of sight. She should have locked him in the larder like he did to her.

Her eyes drift from the fields back to the hailstorm of bullets shooting strips through the beams of the headlights. Strips, like cut up paper in a dog bowl.

Damn him.

The intersections fly past as she presses harder.

Comments (0)