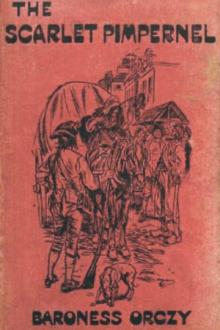

The Triumph of the Scarlet Pimpernel - Baroness Orczy (the little red hen read aloud .txt) 📗

- Author: Baroness Orczy

Book online «The Triumph of the Scarlet Pimpernel - Baroness Orczy (the little red hen read aloud .txt) 📗». Author Baroness Orczy

“Nay: you need have no fear, fair one! I am a lover of sport. I’ll not betray you.”

She frowned, really puzzled this time.

“I do not understand,” she murmured.

“Let us get back to The Fisherman’s Rest,” he retorted with characteristic irrelevance. “Shall we?”

“Milor,” she insisted, “will you explain?”

“There is nothing to explain, dear lady. You have asked me—nay! challenged me—not to betray you to anyone, not even to Lady Blakeney. Very well! I accept your challenge. That is all.”

“You will not tell anyone—anyone, mind you!—that Mme. de Fontenay and Theresia Cabarrus are one and the same?”

“You have my word for that.”

She drew a scarce perceptible sigh of relief.

“Very well then, milor,” she rejoined. “Since I am allowed to go to London, we shall meet there, I hope.”

“Scarcely, dear lady,” he replied, “since I go to France tomorrow.”

This time she gave a little gasp, quickly suppressed—for she hoped milor had not noticed.

“You go to France tomorrow, milor?” she asked.

“As I had the honour to tell you, I go to France tomorrow, and I leave you a free hand to come and go as you please.”

She chose not to notice the taunt; but suddenly, as if moved by an uncontrollable impulse, she said resolutely:

“If you go, I shall go too.”

“I am sure you will, dear lady,” he retorted with a smile. “So there really is no reason why we should linger here. Our mutual friend M. Chauvelin must be impatient to hear the result of this interview.”

She gave a cry of horror and indignation.

“Oh! You—you still think that of me?”

He stood there, smiling, looking down on her with that half-amused, lazy glance of his. He did not actually say anything, but she felt that she had her answer. With a moan of pain, like a child who has been badly hurt, she turned abruptly, and burying her face in her hands she sobbed as if her heart would break. Sir Percy waited quietly for a moment or two, until the first paroxysm of grief had quieted down, and he said gently:

“Madame, I entreat you to compose yourself and to dry your tears. If I have wronged you in my thoughts, I humbly crave your pardon. I pray you to understand that when a man holds human lives in his hands, when he is responsible for the life and safety of those who trust in him, he must be doubly cautious and in his turn trust no one. You have said yourself that now at last in this game of life and death, which I and my friends have played so successfully these last three years, I hold the losing cards. Then must I watch every trick all the more closely, for a sound player can win through the mistakes of his opponent, even if he hold a losing hand.”

But she refused to be comforted.

“You will never know, milor—never—how deeply you have wounded me,” she said through her tears. “And I, who for months past—ever since I knew!—have dreamed of seeing the Scarlet Pimpernel one day! He was the hero of my dreams, the man who stood alone in the mass of self-seeking, vengeful, cowardly humanity as the personification of all that was fine and chivalrous. I longed to see him—just once—to hold his hand—to look into his eyes—and feel a better woman for the experience. Love? It was not love I felt, but hero-worship, pure as one’s love for a starlit night or a spring morning, or a sunset over the hills. I dreamed of the Scarlet Pimpernel, milor; and because of my dreams, which were too vital for perfect discretion, I had to flee from home, suspected, vilified, already condemned. Chance brings me face to face with the hero of my dreams, and he looks on me as that vilest thing on earth: a spy!—a woman who could lie to a man first and send him afterwards to his death!”

Her voice, though more passionate and intense, had nevertheless become more steady. She had at last succeeded in controlling her tears. Sir Percy had listened—quite quietly, as was his wont—to her strange words. There was nothing that he could say to this beautiful woman who was so ingenuously avowing her love for him. It was a curious situation, and in truth he did not relish it—would have given quite a great deal to see it end as speedily as possible. Theresia, fortunately, was gradually gaining the mastery over her own feelings. She dried her eyes, and after a moment or two, of her own accord, she started once more on her way.

Nor did they speak again with one another until they were under the porch of The Fisherman’s Rest. Then Theresia stopped, and with a perfectly simple gesture she held out her hand to Sir Percy.

“We may never meet again on this earth, milor,” she said quietly. “Indeed, I shall pray to le bon Dieu to keep me clear of your path.”

He laughed good-humouredly.

“I very much doubt, dear lady,” he said, “that you will be in earnest when you utter that prayer!”

“You choose to suspect me, milor; and I’ll no longer try to combat your mistrust. But to one more word you must listen: Remember the fable of the lion and the mouse. The invincible Scarlet Pimpernel might one day need the help of Theresia Cabarrus. I would wish you to believe that you can always count on it.”

She extended her hand to him, and he took it, the while his inveterately mocking glance challenged her earnest one. After a moment or two he stooped and kissed her fingertips.

“Let me rather put it differently, dear lady,” he said. “One day the exquisite Theresia Cabarrus—the Egeria of the Terrorists, the fiancée of the Great Tallien—might need the help of the League of the Scarlet Pimpernel.”

“I would sooner die than seek your help, milor,” she protested earnestly.

“Here in Dover, perhaps … but in France? … And you said you were going back to France, in spite of Chauvelin and his pale eyes, and his suspicions

Comments (0)