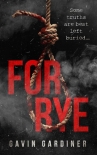

For Rye by Gavin Gardiner (books for 10th graders txt) 📗

- Author: Gavin Gardiner

Book online «For Rye by Gavin Gardiner (books for 10th graders txt) 📗». Author Gavin Gardiner

Nothing.

She heaved again, desperately ignoring the agony of her torn hands and, worse, the hair hanging over her face, but the lid didn’t move. Whether by the passing of decades or a deliberate effort before burial, the wood was sealed. She threw the shovel from the pit and reached out for the smaller spade, lightning exploding over her chasm, rain pouring down its walls in black waterfalls. She wedged the steel of the child-sized implement under the rim and began working the lid.

The coffin creaked in protest until its cover finally snapped free. She raised the panel, groaning at its weight as she straightened her legs and leant it against the rear wall of the pit. She stood with her back to the open box, eyes closed, panting for breath, running her bloody hands over her hair again and again and again. Lightning flickered, a lightbulb expiring, then a dying growl of thunder from across the fields as the rain calmed. The storm stepped back.

Then the smell hit her.

She sprayed vomit over the upturned panel, steadying herself against the glutinous walls. The stench was somehow physical, making itself known even as she held her breath, tangling around her like a net. She spat the taste from her mouth. It was time.

She turned around.

Its hands lay clasped. Dinky shoes pointed to the sky. The suit was in superb condition. A box of liquefied human would have yielded no answers. Luckily, this was something else.

Two pots of black fluid marked hollow, bubbling eye sockets. In place of a nose was a tunnel boring through the centre of its face. Gleaming baby teeth, cleaned to a shine by the rain, huddled behind what used to be seven-year-old lips. Poking out from the tiny open mouth was undertaker’s thread, dancing in the wind, its mouth-shutting duties now as expired as the lips they once bound.

And still, after all these years, those damned red curls.

Renata spotted something wriggling behind its curtain of teeth and dropped the spade. It clattered against steel. She looked down and saw it lying on top of another small spade, also red, also child-sized. She peered down at the engraving on its face:

To our dearest Noah: keep digging.

It was him. Her eyes passed from its desiccated hands to the tiny mouth. There was more she needed to see.

Noah looked almost mummified, skin tight and leathered. Millbury Peak’s frosty seasons had no doubt played a part in the cadaver’s relative preservation, the cold earth having prevented the liquefying she’d half-anticipated. The skull itself, despite the ruined lips and mouth, still held in near perfect form. This was to be the fruit of her labours.

She knelt, knees planted on either side of the blank vessel that had been her brother. The rain, now calmed to a steady drizzle, had rinsed off a little of Noah’s hair, as well as some of the scum encrusted upon the skull, but not enough.

It had to be cleaned completely.

She held out her trembling hands and reached for her brother’s face, his head propped up on a small cushion. The rain renewed its efforts, prompting an eye socket to overflow and weep its thick treacle lazily down into the almost-smiling mouth. The leathery, stiff face looked up at her, empty eyes pleading as they had that fateful night.

The crispy curls snapped in her fingers as she began crudely massaging its dried-out hair, the smooth scalp eventually lying bare beneath her hands. She switched relentlessly from gnawing on her lips to gritting her teeth. Gnawing on lips, gritting her teeth. Back and forth, to and fro. Gnawing, gritting. Gritting, gnawing.

Her fingers, still tangled with a few strands, continued kneading the scum-laden skull until bony white finally emerged through the film of decomposition. She peered closer through the low light at intricate streaks of pink across the pale scalp.

She worked the skull harder, further revealing the pastiche of plastic, rosy-coloured blotches. Running a scum-coated finger over the patterns, she discerned a world map of white oceans and pink landmasses, the very blueprint of the boy’s end. She reached for the spade, not the replica but the spade, and lined its blade against the plastic markings in the bone.

It fit.

The embalmer had done a fine job. Noah’s skull had been patched up and smoothed to perfection. With his curls, there would have been no evidence of the cranial trauma the seven-year-old had suffered. Tonight, the repair job was horrendously visible. She went round the hardened plastic stuffing with the spade head, lining it up to each crack. This had indeed been the instrument of his demise.

Quentin had spoken the truth.

Lightning flashed, but this time in her head.

Pain seared, the usual pain, except it didn’t die. She threw her hands to the sides of her head against rain-plastered hair, teeth clamped. Distantly, she realised this was the end. A brain aneurysm perhaps, or some kind of seizure. Images began falling through the rain.

She looked to the sky, clasping her head through the blinding light of agony.

Through the storm she saw the boy in the road. She felt the accelerator underfoot as her fists tightened around the wheel, then an impact against the bonnet, the yellow raincoat disappearing over the roof. She felt the car skid to a halt, and, in the immensity of the tempest, saw the twisted shape of her brother flat on the gravel. She saw the spade slicing down upon the boy; the red steel before her appear to melt as moonlit, jet-black blood trickled from its blade, covering her hands like tar; the child lying in the middle of the road, dead. She battered her fists against the

Comments (0)