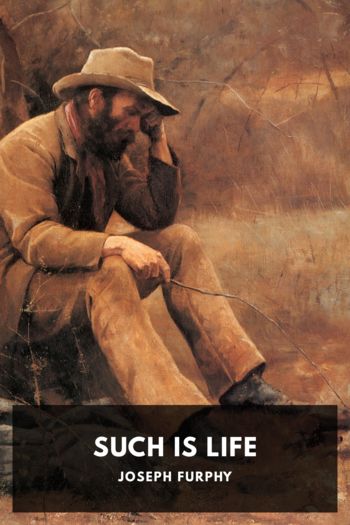

Such Is Life - Joseph Furphy (philippa perry book txt) 📗

- Author: Joseph Furphy

Book online «Such Is Life - Joseph Furphy (philippa perry book txt) 📗». Author Joseph Furphy

My worldly-wise friend, let us draw a lesson from this. If you have never been bushed, your immunity is by no means an evidence of your cleverness, but rather a proof that your experience of the wilderness is small. If you have been bushed, you will remember how, as you struck a place you knew, error was suddenly superseded by a flash of truth; this without volition of judgment on your part, and entirely by force of a presentation of fact which your own personal error—however sincere and stubborn—had never affected, and which you were no longer in a position to repudiate. It has always been my strong impression that this is very much like the revelation which follows death—that is, if conscious individuality be preserved; a thing by no means certain, and, to my mind, not manifestly desirable.

But if, after closing our eyes in death, we open them on an appreciable hereafter—whether one imperceptible fraction of a second, or a million centuries, may intervene—it is as certain as anything can be, that, to most of us, the true east will prove to be our former southwest, and the true west, our former northeast. How many so-called virtues will vanish then; and how many objectionable fads will shine as with the glory of God? This much is certain: that all private wealth, beyond simplest maintenance, will seem as the spoils of the street gutter; that fashion will be as the gilded fly which infests carrion; that “sport” will seem folly that would disgrace an idiot; that military force, embattled on behalf of Royalty, or Aristocracy, or Capital, will seem like—Well, what will it seem like? Already, looking, or rather, squinting, back along our rugged and random track, we perceive that the bloodiest battle ever fought by our badly-bushed forefathers on British soil—and that only one of a series of twelve, in which fathers, sons, brothers, kinsmen, and fellow-slaves exterminated each other—was fought to decide whether a drivelling imbecile or a shameless lecher should bring our said forefathers under the operation of I Samuel, viii. (Read the chapter for yourself, my friend, if you know where you can borrow a Bible; then turn back these pages, and take a second glance at the paragraphs you skimmed over in that unteachable spirit which is the primary element of ignorance—namely, those reflections on the unfettered alternative, followed by rigorous destiny.)

Much more prosaic were my cogitations as I followed the buggy, keeping both switches at work. According to the best calculation I could make, I had ten or twelve miles of country to re-cross, besides the river; and, having no base on the Victorian side, it was a thousand to one against striking my camp on such a night. Of course, I might have groped my way to B⸺’s place; but if you knew Mrs. B⸺’s fatuous appreciation of dilemmas like mine, you would understand that such a thing was not to be thought of. I preferred dealing with strangers alone, and preserving a strict incognito. However, a pair of ⸻ I must have, if nothing else—and that immediately. The buggy was fifteen or twenty yards ahead.

“Archie M⸺!” said I, in a firm, penetrating tone.

The buggy stopped. I repeated my salute.

“All right,” replied Archie. “What’s the matter?”

“Come here; I want you.”

The quadrant of light swept round as the young fellow turned his buggy.

“Leave your buggy, and come alone!” I shouted, careering in a circular orbit, with the light at my very heels.

“Well, I must say you’re hard to please, whoever you are,” remarked Archie, stopping the horse. “Hold the reins, sweetest.”

“Who is it?” asked the damsel, with apprehension in her tone.

“Don’t know, sweetest. Sounds like the voice of one crying in the wilderness.” And the light flashed on him as he felt downward for the step.

“Don’t go!” she exclaimed.

“Never mind her, Archie!” I called out. “She’s a fool. Come on!”

“What on earth’s the matter with you?” asked Archie, addressing the darkness in my direction.

“I’m clothed in tribulation. Can’t explain further. Come on! O, come on!”

“Don’t go, I tell you, Archie!” And in the bright light of the off lamp, I saw her clutch the after part of his coat as he stood on the footboard.

“I must go, sweetest—”

“Good lad!” I exclaimed.

“I’ll be back in a minute. Let go, sweetest.”

“Don’t leave me, Archie. I’m frightened. Just a few minutes ago, I saw a white thing gliding past.”

“Spectral illusion, most likely. There was a hut-keeper murdered here by the blacks, thirty years ago, and they say he walks occasionally. But he can’t hurt you, even if he tried. Now let go, sweetest, and I’ll say you’re a good girl.”

“Archie, you’re cruel; and I love you. Don’t leave me. Fn-n-n, ehn-n-n, ehn-n-n!” Sweetest was in tears.

“This is ridiculous!” I exclaimed. “Come on, Archie; I won’t keep you a minute. The mountain can’t go to Muhammad; and to state the alternative would be an insult to your erudition. Come on!”

“O, Archie, let’s get away out of this fearful place,” sobbed the wretched obstruction. “Do what I ask you this once, and I’ll be like a slave the rest of my life.”

“Well, mind you don’t forget when the fright’s over,” replied Archie, resuming his seat. “That poor beggar has something on his mind, whoever he is; but he’ll have to pay the penalty of his dignity.”

“Too true,” said I to myself, as Archie started off at a trot; “for the dignity is like that of Pompey’s statue, ‘th’ austerest form of naked majesty’—a dignity I would gladly

Comments (0)