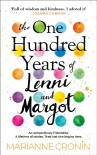

The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot by Marianne Cronin (e reader books txt) 📗

- Author: Marianne Cronin

Book online «The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot by Marianne Cronin (e reader books txt) 📗». Author Marianne Cronin

This time, nobody fell asleep and I didn’t feel like laughing. I wanted to stop the clocks. I wanted Arthur to stay. And I was worried for Arthur – what would happen to him? Did he have a pension? Would Mrs Hill still make him those egg and cress sandwiches when he was no longer a priest? And what in God’s name was he going to do all day?

All too soon, it was over.

‘Go in peace to love and serve the Lord,’ he said. And I didn’t realize I was clapping until I was already doing it. From further down the pew, Margot joined in and the clap grew, until a ripple of applause was emanating from the various artists of the Rose Room.

Arthur blushed and nodded. ‘Thank you.’

As we made our way, oh so slowly, to the door, Arthur asked Pippa, ‘Can I have a word with Lenni? It won’t take a second.’

Pippa agreed and shuffled out with the others.

‘You know,’ Margot said to Else as they made their way to the door, ‘Father Arthur looks very familiar, but I can’t quite put my finger on it. Do you think he’s been on the television?’

‘Well, it was a very unusual service,’ I heard Else saying from the corridor. ‘My first husband was an Anglican, my second a Methodist and my third a Catholic, and it seemed like a mix of all three.’ I didn’t get to hear whether anyone agreed with her or not, because the heavy door closed behind them.

I walked back down the aisle to see Father Arthur with a sad smile.

‘Thank you,’ he said.

‘For what?’

‘I’m going to miss you, Lenni.’

I reached out and gave him a hug. His robes smelled of fabric conditioner, which was an absurdly homely smell for sacred robes. ‘Thanks for everything, Father Arthur,’ I said into his shoulder.

He drew back.

‘Can I come and visit?’ he asked.

‘If you don’t, I’ll never forgive you,’ I said. I reached out a hand to lean on the pew beside me because everything was hurting. I had (on pain of death) forced Pippa to leave ‘my’ wheelchair outside the chapel.

‘I promise I will visit,’ he said, and then he stopped. ‘You asked me, Lenni, to tell you something true, when we’d only just met. Do you remember?’

‘I do.’

‘Well, this is my final truth: if I had a granddaughter, I would want her to be exactly like you.’

And because he was about to cry, I held out my right hand. He looked confused.

‘It started with a handshake.’ I smiled.

Understanding, he put his hand in mine.

‘Until the next time, Lenni,’ he said, shaking me by the hand.

And when I had taken back my hand from his, he said, ‘Take care,’ with such force that it was as though he thought the more emphatically he said it, the more likely it was to happen. That if only I could just bloody take care of myself, I might not die.

I was putting a lot of work into not crying, so I left him standing in the chapel and managed to make it to the wheelchair without stumbling. Taking care, as he hoped I would.

And then it was over. Pippa very kindly wheeled my chair for me, and we occupants of the Rose Room made our way back to our art supplies. ‘Thank you,’ I said to them, and when they told me it had been no trouble, I had to stare up at the bright lights on the ceiling of the corridor to keep from crying.

Sixty

NEW NURSE WHEELED me to the Rose Room to celebrate the latest of our landmark numbers. We forgot to celebrate fifty, the half-century, so sixty would have to suffice.

‘I’m having trouble knowing where to store them,’ Pippa said to nobody in particular, as she pulled the bigger pieces down from one of the shelves over the sink and laid them on the table. She placed them carefully around the room, seeming to have some preferred order. The colours were what struck me most. A night sky over a cottage in Henley-in-Arden, a chicken with most of its feathers missing, my terrible rendering of my sparsely attended tenth birthday party.

‘Is this one of yours, Lenni?’ New Nurse said, pointing to Margot’s painting of the green park where she’d sat and waited for The Professor to leave.

‘Well, now you’re just being mean.’

‘What?’

‘Of course it isn’t mine!’

I got up out of the wheelchair and waited for New Nurse to try and stop me. When she didn’t, I wanted to push my luck, to try running, or skipping, or sitting on one of the tables swinging my legs. I stood by my painting of my mother and a waiting taxi, as viewed from a great height.

‘It’s amazing,’ New Nurse said.

‘What is?’

‘All of it,’ New Nurse replied, a serious look clouding her face. ‘You’ve done something amazing here. And Margot too, of course.’

‘It was all Lenni’s idea,’ Margot said.

‘She’s a bright one.’ Pippa smiled.

I realized then that but for sixty pictures, some art supplies and my still-beating heart, they could have been at my funeral, discussing me, talking of my achievements with a sentimental over-exaggeration of my good qualities, nursing stale sandwiches on their plates and wondering what I might have done with my life if only I’d lived.

That was all I could think. Not, Hey, we’ve painted sixty pictures, but, This is it. This mothering, sombre way that they’ll talk about me when I’m … wherever I end up. I wanted there to be more. I wanted there to be so much more. But maybe everyone wants that.

I wanted them to be able to say,

Comments (0)