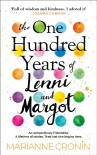

The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot by Marianne Cronin (e reader books txt) 📗

- Author: Marianne Cronin

Book online «The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot by Marianne Cronin (e reader books txt) 📗». Author Marianne Cronin

‘I have to go,’ I said, barely above a whisper.

‘Well, goodbye then, Margot,’ he said, ‘and thank you for the kiss.’ And he winked.

Several months later, Humphrey James passed away peacefully in his sleep, sitting beside his telescope in his armchair by the window.

Morning

West Midlands, May 1998

Margot James is still Sixty-Seven Years Old

purple is the colour of morning

the moment

when the sullen sphere rolls around

and there’s a shift

from black to biro blue

light,

dawn,

day.

the space of sunlight

that we predict will last a few minutes longer than the one

before

and we’ll call it wednesday

but it isn’t wednesday, not one in seven,

but new,

a gap of light between

the darkness

and who can say for certain

that it will come again?

in this light, they carry the coffin

on this wednesday, we say goodbye

our sadness a gap of darkness between

the light

and a priest in robes of violet and white

informs us,

‘purple is the colour of mourning’

Humphrey’s funeral was very well attended – all the staff from the observatory and several from overseas were there; his side of the family came in great numbers, led by his sister, who stayed with me for the week before to help with the preparations. Even the nurse with the cardigan from the care home came to say goodbye.

At the funeral, I read the Sarah Williams poem he’d written down for me after our first meeting, because my own words didn’t suffice. I wrote him his own personal poem the night after the funeral, when sleep evaded me and all I could do to calm myself was look at the stars.

And then, everything was done. His sister had to go back home and I found myself alone. Doing the washing up.

I’d put the radio on to distract myself from thinking about him – about the haunting knowledge that his body had been there in the box in the church where we were all sitting. That inside that box he was lying, cold, as though he were sleeping. The radio was playing a pop song. So I sang. I sang along with a song I hadn’t even realized I knew the words to. And when the images of his coffin being lowered into the ground swam into my vision, I sang louder. When the sight of his sister crying and throwing her fistful of dirt into the open grave came into my mind, I sang louder still. And then I was no longer at the funeral but in the care home, in The Field. And I had his face in my hands, and he was looking up at me.

I’d kissed him.

And then he’d said …

A plate I’d just balanced on top of a saucepan on the drying rack slipped out of its spot and shattered on the floor.

And I found myself on the floor beside the plate, because I knew then, in my bones, that the last time I saw Humphrey James he hadn’t forgotten me. He’d been pretending.

He’d kissed me back. He’d smiled. ‘It’s a once-in-a-lifetime astral event,’ he’d said. A once-in-a-lifetime astral event.

And more than that: when he told me to find my love, he told me to ‘find him … or her’, when just the day before he’d asked me about Meena, though we hadn’t spoken of her in years.

That terrible, wonderful man had pretended not to know me so that he could say goodbye while he still knew who I was. He’d saved me from those visits, and in his own way he had set me free. And, no doubt, he was able to check if I really would keep my promise.

I laughed for about twenty minutes because the idea of Humphrey pretending not to know me was so infuriating and silly and so very him. And then I cried.

Light … Dawn … Day

MY FATHER IS standing at the end of my bed.

Or he isn’t.

(I haven’t been well.)

He looks smaller than I remember.

I go to talk and become aware of a mask on my face. My words echo back at me. I pull the mask off, and recall a conversation I had with a nurse. It’s to help me sleep, or to keep me awake. To help me live, or to help me die. One of those.

He says something in Swedish. The verbs don’t agree and neither do I.

‘Hi, pickle,’ he says, holding my hand and rubbing his thumb over the cannula where it burrows in. Back and forth, like a rhythm. It hurts, but I can’t remember the words in either language to get him to stop.

You would think after all this time there would be a lot to say, that I would be bursting with stories of my adventures and he would be bursting with his. But nobody says anything. Maybe it is a dream, after all, and my brain is struggling to generate his voice. What was it like? High? Low?

‘Lenni,’ I tell him, and then immediately wonder why, but I’ve said it now and I have to watch his face crumple in confusion. My father grabs the arm of a passing blur and asks me to repeat what I’ve said, but I don’t remember.

‘Is it about my mother? She’s eighty-three. We’re almost one hundred.’

‘The anaesthetic can cause some confusion,’ the blur says to him, and he sits down.

‘Did you go to Poland?’ I think I ask.

He nods and shows me a black and grey picture of a bean, I think.

‘I had to tell you as soon as we were sure,’ he says, ‘you’re going to be a big sister.’

‘It’s Arthur,’ I say.

‘What is?’

I shake my head and then wonder what exactly we both think we’re talking about.

‘It’s Father Arthur.’

My father turns to Agnieszka and says with panic, ‘She doesn’t recognize me.’

‘She wears purple for Humphrey,’ I say, connecting the thoughts at last. ‘Because she’s mourning. And it’s morning. That’s why she always wears purple.’

‘Lenni?’

And then Agnieszka is

Comments (0)