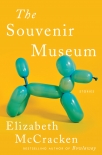

The Souvenir Museum by Elizabeth McCracken (essential books to read .txt) 📗

- Author: Elizabeth McCracken

Book online «The Souvenir Museum by Elizabeth McCracken (essential books to read .txt) 📗». Author Elizabeth McCracken

But Louis: Louis had forgotten where he was again. This was his secret. These days, when he daydreamed (dreamy Louis, all the time), he lost himself. His brain went along its track and when coming around did not recognize the station. Still, a station: you could make sense of it, you could navigate any train station in the world, despite the language, the local customs. Train stations obeyed. Keep tight till you know where you are, you’ll be all right. Outside the boat, the water flashed, bent, bulged, and fish—fish! He said it to his son, “Fish!”

“Dolphins!” said David. “Look!”

Blue sky and dolphins, the wind battering their ears, a laughing girl, a picnic at their feet: a triumph.

“Will there definitely be puffins?” a tall Swedish woman asked.

“Were yesterday,” said Robby.

“Is it guaranteed?”

“Puffins yesterday, most likely puffins today,” Robby said. “Sir!”

Louis was leaning over the side of the boat, kneeling on the bench and staring at the water. The Swedish woman grabbed him by the collar of his coat. “Upla,” she said, gentling Louis back on his seat.

“Hey,” said Robby to David. “Look after your father.”

“He’s—”

“Look after him,” said Robby.

“All right, folks,” said the voice of God. “We’re going to go take a closer look at our friends on that rock.”

The rocks in a line on the larger rock lifted their heads and revealed themselves to be seals.

“Oh, the sweet things,” said Louis, and the laughing girl gasped, went silent, laughed again. “Puffin,” Louis said suddenly; he thrust his finger skyward at a flying bird—“Puffin, puffin.”

“Puffin,” the girl agreed.

“Puffins can’t fly,” said David.

“Yes, they can,” said several voices in several accents.

“You’re thinking of penguins,” said Robby.

“I thought—”

“Puffins fly,” said Robby firmly. Then he leaned in and said in David’s ear, so the children couldn’t hear, “Don’t confuse them with penguins. They fuckin’ hate that.”

The website for the tour had said that the path to the puffins was rocky. What they meant was boulderous. Each rock was the size of a human head or larger, and loose, and shifted when you stepped. “Look for the flat ones!” called Robby, who would stay on the boat. People stood on their rocks, trying to figure out which way might not kill them. Disaster, thought David. He tried to keep the picnic bag on his back, but it kept swinging to his front and knocking him off balance. His mother might have been delighted by a fancy picnic; every morning for years his father had stuck a deviled ham sandwich in his back pocket and sat on it till lunchtime, when it was warm and flat and ready to eat. He needed, he had always needed, so little. David started crawling over the rocks on all fours, the bag a ringing bell of stupidity. His father was seventy-seven. They had no business here. The tour company should have warned him.

“Are you all right?” the Englishwoman called.

David straightened up to see his father standing like a statue on a rock, facing a little inlet. Marooned. He’d gone the wrong direction.

“Do you need a hand, Dad?”

No answer. His father could do this sometimes, get lost in thought, but in an armchair. What happened if an old man broke his hip on the Treshnish Isles? Would he be airlifted to safety? Buried at sea?

“Dad!” David shouted, then all around him, the voices of his fellow passengers like birdcall: “Sir!” “Sir!” “Hey!” “Buddy!” “My friend!” “Sir!”

Slowly, his father pivoted. He gave a fluttering wave with the back of his hand and made his way tightroperly across the rocks.

On the shore, they were confronted with a muddy path straight up a hill. David struggled with the bag. Ahead of him, Louis walked up at an angle, as though against the wind, dipping his fingertips in the mud. Then they stood on a wide green plateau. David turned and regarded the view: blue sky above, slate sea below, grass and—

—his father said, in a fond voice, “Oh, little brothers. Look, Davey, look at them.”

White-breasted, orange-beaked, hopping along the ground, birds the size of books: puffins, dozens of them, so many you couldn’t count, or see them as individuals; they constituted mere puffinosity. People walked right up and took pictures. They were not seagulls nor pigeons, who begged for food or stole it: they were merely the locals, accustomed to the seasonal influx of gawkers. Patient, accessible, aloof. They could fly but chose not to. David pulled out his phone. He almost laughed when the bird in front of him appeared on the screen.

“I didn’t think they’d be so close,” he said. “Why aren’t they afraid?”

“Because their predators are,” said Louis. This fact was a shard of pottery: it lay there; he snatched it up. “The puffins know that if humans are near, their predators won’t be. They live in burrows. See them hopping in and out?”

“They’re so sweet,” said David wonderingly. He wanted to pick one up, dandle it on his knee. There was more island to scale—the voice of God had told them that the views from the top of Lunga were astonishing—but why risk it when they were here and already astonished? He set down the bag. The puffins were endearing and ridiculous, with expressions that suggested they thought the same of you, coming all this way to gawk at puffins. He pulled out the cheese in

Comments (0)