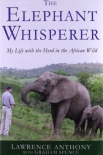

The Elephant Whisperer: My Life With the Herd in the African Wild by Lawrence Anthony (best motivational books .TXT) 📗

- Author: Lawrence Anthony

Book online «The Elephant Whisperer: My Life With the Herd in the African Wild by Lawrence Anthony (best motivational books .TXT) 📗». Author Lawrence Anthony

Max, who had his head out of the passenger’s window, spilled across the cab and onto my lap.

‘Straight, straight!’ shouted Bheki, thumping on the roof to get my attention. Ducking the barbed branches and navigating from his elevated position he directed me through the tangled bush and a few jarring minutes later we arrived at the carcass.

It was a wildebeest, albeit barely recognizable as the corpse had been messily butchered. But that was not why we were here. Lying close to the carcass was a dead vulture and further afield I could see another. Both of them had their heads hacked off.

One of the most accurate indicators of a vibrant game reserve is a healthy vulture population. I remembered when we first arrived at Thula Thula searching vainly for breeding pairs. If you don’t have large numbers of game you’re not going to have resident vultures. In those early days these great, graceful scavengers used to flock in from the Umfolozigame reserve, tiny specks in the sky surfing the thermals at incredible altitudes as they searched for carrion.

Today, with our healthy game population, we had plenty of breeding pairs ensconced in their nests at the top of the great trees lining the river, raising their chicks seasonally and generally doing well for themselves. But now out of the blue, vultures had become top of the poaching hit list and for bizarre reasons that no conservationist could ever have guessed. The once-belittled vulture had become an extremely potent good luck totem among the sangomas.

The reason was simple: money. A national lottery had recently been introduced with huge weekly payouts. If you guessed the six winning Lotto numbers you were an instant millionaire. Most of us know that playing a lottery is pure luck. But in Africa, predicting the winning numbers has become a mysterious art verging on the occult. A growing number of South Africans believed that there was only one way to scoop the pools, and that’s to consult your ancestors. And who was the vital link between mortals and spirits? Why, the sangomas, of course.

This is not just primitive rural superstition; ancestral guidance is practised by all kinds of people, from illiterate herd boys to multi-degreed university professors. If you don’t understand the power of this belief, you will never truly grasp the rich albeit often incomprehensible spirituality of Africa. According to some unscrupulous sangomas, the most powerful Lotto muthi was dried vulture brain. So as the race to become an instant millionaire heated up, the humble vulture was being poached almost to extinction in some game reserves.

Muthi is a collective Zulu term given both to magic spells and to the foul-tasting potions prepared by sangomas. It can be good muthi, or bad muthi, the latter always associated with witchcraft. Dried vulture brain was considered to be very good muthi indeed. So much so that sangomas toldtheir gullible clients that if they placed a slice of it under their pillows at night, their ancestors would whisper the winning Lotto numbers to them in their dreams.

One of the most inconceivable aspects of vulture muthi is how someone blindly places so much faith in something so manifestly unreliable. Thousands of desperately poor peasants, totally ignorant of basic gambling odds, were placing all they could afford into a lottery in which there were precious few winners. Each week, millions lost their hard-earned wages, with or without vulture brains under their pillows.

This translated into big business for sangomas. A tiny sliver of vulture’s brain cost about ten US dollars, which is a lot of money in outback Zululand. Yet despite there being only a few winners, visits to sangomas skyrocketed. And no matter how much they lost, villagers continued forking out wads of cash for more vulture brains, which they religiously placed under their pillows, waiting for their ancestors to murmur the magic numbers.

The end result was distressingly obvious: people squandered lifesavings and vultures continued to die – so much so that in some game reserves breeding pairs were becoming increasingly rare. In fact, the true Lotto winners were the sangomas.

We clambered out of the vehicle, dodged a series of tall brown termite mounds which had blocked the Land Rover’s passage and closely studied the gory remains of the wildebeest, looking for the cause as we always do with an unnatural death. Other vultures, attracted to the carcass like iron filings to a magnet, either circled above or gathered atop nearby trees, disturbed by our presence.

For obvious reasons, a contagious disease fatality is our biggest fear as it can spread in a blink to other animals. We first checked for nasal discharges, tick loads, injuries, and what the overall condition of the animal had been prior to its demise. This wildebeest had been fit and healthy and thecause of death, while not immediately obvious from the hacked remains, seemed to be a bullet.

Bheki and Ngwenya put down their rifles and were moving in to turn over the body so we could inspect the other side, when something made me stop them.

‘Poison,’ I said, slowly realizing what had happened. ‘I think there is poison here. Don’t touch the body until we inspect the vultures.’

They looked up surprised, but said nothing and stepped back, following me as I walked to the first headless bird.

I kept a close eye on Max, ordering him to ‘heel’ often enough to let him know he must not leave my side, not even for a sniff of the dead creatures. A noseful of strychnine, insecticide, or whatever it was they were using would certainly do him no good.

I had never been that close to a white-backed vulture before. With a seven-foot wingspan it is a big, impressive bird by any standards, but how undignified and ignominious it looked in death. This superb sultan of the skies lay there headless, sprawled awkwardly with one huge wing jutting into the grass. There was not a mark on it and judging by the distance from the wildebeest carcass it must have died very

Comments (0)