An Introduction to Philosophy - George Stuart Fullerton (i can read book club TXT) 📗

- Author: George Stuart Fullerton

- Performer: -

Book online «An Introduction to Philosophy - George Stuart Fullerton (i can read book club TXT) 📗». Author George Stuart Fullerton

85. THE VALUE OF DIFFERENT POINTS OF VIEW.—The man who has not read is like the man who has not traveled—he is not an intelligent critic, for he has nothing with which to compare what falls within the little circle of his experiences. That the prevailing architecture of a town is ugly can scarcely impress one who is acquainted with no other town. If we live in a community in which men's manners are not good, and their standard of living not the highest, our attention does not dwell much upon the fact, unless some contrasted experience wakes within us a clear consciousness of the difference. That to which we are accustomed we accept uncritically and unreflectively. It is difficult for us to see it somewhat as one might see it to whom it came as a new experience.

Of course, there may be in the one town buildings of more and of less architectural beauty; and there may be in the one community differences of opinion that furnish intellectual stimulus and keep awake the critical spirit. Still, there is such a thing as a prevalent type of architecture, and there is such a thing as the spirit of the times. He who is carried along by the spirit of the age may easily conclude that what is, is right, because he hears few raise their voices in protest.

To estimate justly the type of thought in which he has been brought up, he must have something with which to compare it. He must stand at a distance, and try to judge it as he would judge a type of doctrine presented to him for the first rime. And in the accomplishment of this task he can find no greater aid than the study of the history of philosophy.

It is at first something of a shock to a man to discover that assumptions which he has been accustomed to make without question have been frankly repudiated by men quite as clever as he, and, perhaps, more critical. It opens the eyes to see that his standards of worth have been weighed by others and have been found wanting. It may well incline him to reexamine reasonings in which he has detected no flaw, when he finds that acute minds have tried them before, and have declared them faulty.

Nor can it be without its influence upon his judgment of the significance of a doctrine, when it becomes plain to him that this significance can scarcely be fully comprehended until the history of the doctrine is known. For example, he thinks of the mind as somehow in the body, as interacting with it, as a substance, and as immaterial. In the course of his reading it begins to dawn upon his consciousness that he has not thought all this out for himself; he has taken these notions from others, who in turn have had them from their predecessors. He begins to realize that he is not resting upon evidence independently found in his own experience, but has upon his hands a sheaf of opinions which are the echoes of old philosophies, and whose rise and development can be traced over the stretch of the centuries. Can he help asking himself, when he sees this, whether the opinions in question express the truth and the whole truth? Is he not forced to take the critical attitude toward them?

And when he views the succession of systems which pass in review before him, noting how a truth may be dimly seen by one writer, denied by another, taken up again and made clearer by a third, and so on, how can he avoid the reflection that, as there was some error mixed with the truth presented in earlier systems, so there probably is some error in whatever may happen to be the form of doctrine generally received in his own time? The evolution of humanity is not yet at an end; men still struggle to see clearly, and fall short of the ideal; it must be a good thing to be freed from the dogmatic assumption of finality natural to the man of limited outlook. In studying the history of philosophy sympathetically we are not merely calling to our aid critics who possess the advantage of seeing things from a different point of view, but we are reminding ourselves that we, too, are human and fallible.

86. PHILOSOPHY AS POETRY, AND PHILOSOPHY AS SCIENCE.—The recognition of the truth that the problems of reflection do not admit of easy solution and that verification can scarcely be expected as it can in the fields of the special sciences, need not, even when it is brought home to us, as it is apt to be, by the study of the history of philosophy, lead us to believe that philosophies are like the fashions, a something gotten up to suit the taste of the day, and to be dismissed without regret as soon as that taste changes.

Philosophy is sometimes compared with poetry. It is argued that each age must have its own poetry, even though it be inferior to that which it has inherited from the past. Just so, it is said, each age must have its own philosophy, and the philosophy of an earlier age will not satisfy its demands. The implication is that in dealing with philosophy we are not concerned with what is true or untrue in itself considered, but with what is satisfying to us or the reverse.

Now, it would sound absurd to say that each age must have its own geometry or its own physics. The fact that it has long been known that the sum of the interior angles of a plane triangle is equal to two right angles, does not warrant me in repudiating that truth; nor am I justified in doing so, and in believing the opposite, merely because I find the statement uninteresting or distasteful. When we are dealing with such matters as these, we recognize that truth is truth, and that, if we mistake it or refuse to recognize it, so much the worse for us.

Is it otherwise in philosophy? Is it a perfectly proper thing that, in one age, men should be idealists, and in another, materialists; in one, theists, and in another, agnostics? Is the distinction between true and false nothing else than the distinction between what is in harmony with the spirit of the times and what is not?

That it is natural that there should be such fluctuations of opinion, we may freely admit. Many things influence a man to embrace a given type of doctrine, and, as we have seen, verification is a difficult problem. But have we here, any more than in other fields, the right to assume that a doctrine was true at a given time merely because it seemed to men true at that time, or because they found it pleasing? The history of science reveals that many things have long been believed to be true, and, indeed, to be bound up with what were regarded as the highest interests of man, and that these same things have later been discovered to be false—not false merely for a later age, but false for all time; as false when they were believed in as when they were exploded and known to be exploded. No man of sense believes that the Ptolemaic system was true for a while, and that then the Copernican became true. We say that the former only seemed true, and that the enthusiasm of its adherents was a mistaken enthusiasm.

It is well to remember that philosophies are brought forward because it is believed or hoped that they are true. A fairy tale may be recited and may be approved, although no one dreams of attaching faith to the events narrated in it. But a philosophy attempts to give us some account of the nature of the world in which we live. If the philosopher frankly abandons the attempt to tell us what is true, and with a Celtic generosity addresses himself to the task of saying what will be agreeable to us, he loses his right to the title. It is not enough that he stirs our emotions, and works up his unrealities into something resembling a poem. It is not primarily his task to please, as it is not the task of the serious worker in science to please those whom he is called upon to instruct. Truth is truth, whether it be scientific truth or philosophical truth. And error, no matter how agreeable or how nicely adjusted to the temper of the times, is always error. If it is error in a field in which the detection and exposure of error is difficult, it is the more dangerous, and the more should we be on our guard against it.

We may, then, accept the lesson of the history of philosophy, to wit, that we have no right to regard any given doctrine as final in such a sense that it need no longer be held tentatively and as subject to possible revision; but we need not, on that account, deny that philosophy is, what it has in the past been believed to be, an earnest search for truth. A philosophy that did not even profess to be this would not be listened to at all. It would be regarded as too trivial to merit serious attention. If we take the word "science" in the broad sense to indicate a knowledge of the truth more exact and satisfactory than that which obtains in common life, we may say that every philosophy worthy of the name is, at least, an attempt at scientific knowledge. Of course, this sense of the word "science" should not be confused with that in which it has been used elsewhere in this volume.

87. HOW TO READ THE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY.—He who takes up the history of philosophy for the first time is apt to be impressed with the fact that he is reading something that might not inaptly be called the history of human error.

It begins with crude and, to the superficial spectator, seemingly childish attempts in the field of physical science. There are clever guesses at the nature of the physical world, but the boldest of speculations are entered upon with no apparent recognition of the difficulty of the task undertaken, and with no realization of the need for caution. Somewhat later a different class of problems makes its appearance—the problems which have to do with the mind and with the nature of knowledge, reflective problems which scarcely seem to have come fairly within the horizon of the earliest thinkers.

These problems even the beginner may be willing to recognize as philosophical; but he may conscientiously harbor a doubt as to the desirability of spending time upon the solutions which are offered. System rises after system, and confronts him with what appear to be new questions and new answers. It seems as though each philosopher were constructing a world for himself independently, and commanding him to accept it, without first convincing him of his right to assume this tone of authority and to set up for an oracle. In all this conflict of opinions where shall we seek for truth? Why should we accept one man as a teacher rather than another? Is not the lesson to be gathered from the whole procession of systems best summed up in the dictum of Protagoras: "Man is the measure of all things"—each has his own truth, and this need not be truth to another?

This, I say, is a first impression and a natural one. I hasten to add: this should not be the last impression of those who read with thoughtful attention.

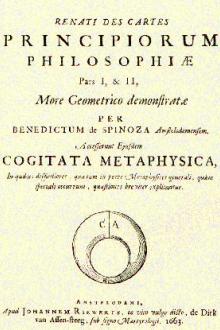

One thing should be emphasized at the outset: nothing will so often bear rereading as the history of philosophy. When we go over the ground after we have obtained a first acquaintance with the teachings of the different philosophers, we begin to realize that what we have in our hands is, in a sense, a connected whole. We see that if Plato and Aristotle had not lived, we could not have had the philosophy which passed current in the Middle Ages and furnished a foundation for the teachings of the Church. We realize that without this latter we could not have had Descartes, and without Descartes we could not have had Locke and Berkeley and Hume. And had not these lived, we should not have had Kant and his successors. Other philosophies we should undoubtedly have had, for

Comments (0)