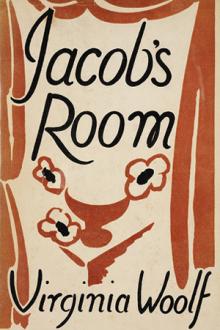

Jacob's Room - Virginia Woolf (polar express read aloud txt) 📗

- Author: Virginia Woolf

- Performer: 0140185704

Book online «Jacob's Room - Virginia Woolf (polar express read aloud txt) 📗». Author Virginia Woolf

Greek boy’s head. But he would respect still. A woman, divining the

priest, would, involuntarily, despise.

Cowan, Erasmus Cowan, sipped his port alone, or with one rosy little

man, whose memory held precisely the same span of time; sipped his port,

and told his stories, and without book before him intoned Latin, Virgil

and Catullus, as if language were wine upon his lips. Only—sometimes it

will come over one—what if the poet strode in? “THIS my image?” he

might ask, pointing to the chubby man, whose brain is, after all,

Virgil’s representative among us, though the body gluttonize, and as for

arms, bees, or even the plough, Cowan takes his trips abroad with a

French novel in his pocket, a rug about his knees, and is thankful to be

home again in his place, in his line, holding up in his snug little

mirror the image of Virgil, all rayed round with good stories of the

dons of Trinity and red beams of port. But language is wine upon his

lips. Nowhere else would Virgil hear the like. And though, as she goes

sauntering along the Backs, old Miss Umphelby sings him melodiously

enough, accurately too, she is always brought up by this question as she

reaches Clare Bridge: “But if I met him, what should I wear?”—and then,

taking her way up the avenue towards Newnham, she lets her fancy play

upon other details of men’s meeting with women which have never got into

print. Her lectures, therefore, are not half so well attended as those

of Cowan, and the thing she might have said in elucidation of the text

for ever left out. In short, face a teacher with the image of the taught

and the mirror breaks. But Cowan sipped his port, his exaltation over,

no longer the representative of Virgil. No, the builder, assessor,

surveyor, rather; ruling lines between names, hanging lists above doors.

Such is the fabric through which the light must shine, if shine it can—

the light of all these languages, Chinese and Russian, Persian and

Arabic, of symbols and figures, of history, of things that are known and

things that are about to be known. So that if at night, far out at sea

over the tumbling waves, one saw a haze on the waters, a city

illuminated, a whiteness even in the sky, such as that now over the Hall

of Trinity where they’re still dining, or washing up plates, that would

be the light burning there—the light of Cambridge.

“Let’s go round to Simeon’s room,” said Jacob, and they rolled up the

map, having got the whole thing settled.

All the lights were coming out round the court, and falling on the

cobbles, picking out dark patches of grass and single daisies. The young

men were now back in their rooms. Heaven knows what they were doing.

What was it that could DROP like that? And leaning down over a foaming

window-box, one stopped another hurrying past, and upstairs they went

and down they went, until a sort of fulness settled on the court, the

hive full of bees, the bees home thick with gold, drowsy, humming,

suddenly vocal; the Moonlight Sonata answered by a waltz.

The Moonlight Sonata tinkled away; the waltz crashed. Although young men

still went in and out, they walked as if keeping engagements. Now and

then there was a thud, as if some heavy piece of furniture had fallen,

unexpectedly, of its own accord, not in the general stir of life after

dinner. One supposed that young men raised their eyes from their books

as the furniture fell. Were they reading? Certainly there was a sense of

concentration in the air. Behind the grey walls sat so many young men,

some undoubtedly reading, magazines, shilling shockers, no doubt; legs,

perhaps, over the arms of chairs; smoking; sprawling over tables, and

writing while their heads went round in a circle as the pen moved—

simple young men, these, who would—but there is no need to think of

them grown old; others eating sweets; here they boxed; and, well, Mr.

Hawkins must have been mad suddenly to throw up his window and bawl:

“Jo—seph! Jo—seph!” and then he ran as hard as ever he could across

the court, while an elderly man, in a green apron, carrying an immense

pile of tin covers, hesitated, balanced, and then went on. But this was

a diversion. There were young men who read, lying in shallow arm-chairs,

holding their books as if they had hold in their hands of something that

would see them through; they being all in a torment, coming from midland

towns, clergymen’s sons. Others read Keats. And those long histories in

many volumes—surely some one was now beginning at the beginning in

order to understand the Holy Roman Empire, as one must. That was part of

the concentration, though it would be dangerous on a hot spring night—

dangerous, perhaps, to concentrate too much upon single books, actual

chapters, when at any moment the door opened and Jacob appeared; or

Richard Bonamy, reading Keats no longer, began making long pink spills

from an old newspaper, bending forward, and looking eager and contented

no more, but almost fierce. Why? Only perhaps that Keats died young—one

wants to write poetry too and to love—oh, the brutes! It’s damnably

difficult. But, after all, not so difficult if on the next staircase, in

the large room, there are two, three, five young men all convinced of

this—of brutality, that is, and the clear division between right and

wrong. There was a sofa, chairs, a square table, and the window being

open, one could see how they sat—legs issuing here, one there crumpled

in a corner of the sofa; and, presumably, for you could not see him,

somebody stood by the fender, talking. Anyhow, Jacob, who sat astride a

chair and ate dates from a long box, burst out laughing. The answer came

from the sofa corner; for his pipe was held in the air, then replaced.

Jacob wheeled round. He had something to say to THAT, though the sturdy

red-haired boy at the table seemed to deny it, wagging his head slowly

from side to side; and then, taking out his penknife, he dug the point

of it again and again into a knot in the table, as if affirming that the

voice from the fender spoke the truth—which Jacob could not deny.

Possibly, when he had done arranging the date-stones, he might find

something to say to it—indeed his lips opened—only then there broke

out a roar of laughter.

The laughter died in the air. The sound of it could scarcely have

reached any one standing by the Chapel, which stretched along the

opposite side of the court. The laughter died out, and only gestures of

arms, movements of bodies, could be seen shaping something in the room.

Was it an argument? A bet on the boat races? Was it nothing of the sort?

What was shaped by the arms and bodies moving in the twilight room?

A step or two beyond the window there was nothing at all, except the

enclosing buildings—chimneys upright, roofs horizontal; too much brick

and building for a May night, perhaps. And then before one’s eyes would

come the bare hills of Turkey—sharp lines, dry earth, coloured flowers,

and colour on the shoulders of the women, standing naked-legged in the

stream to beat linen on the stones. The stream made loops of water round

their ankles. But none of that could show clearly through the swaddlings

and blanketings of the Cambridge night. The stroke of the clock even was

muffled; as if intoned by somebody reverent from a pulpit; as if

generations of learned men heard the last hour go rolling through their

ranks and issued it, already smooth and time-worn, with their blessing,

for the use of the living.

Was it to receive this gift from the past that the young man came to the

window and stood there, looking out across the court? It was Jacob. He

stood smoking his pipe while the last stroke of the clock purred softly

round him. Perhaps there had been an argument. He looked satisfied;

indeed masterly; which expression changed slightly as he stood there,

the sound of the clock conveying to him (it may be) a sense of old

buildings and time; and himself the inheritor; and then to-morrow; and

friends; at the thought of whom, in sheer confidence and pleasure, it

seemed, he yawned and stretched himself.

Meanwhile behind him the shape they had made, whether by argument or

not, the spiritual shape, hard yet ephemeral, as of glass compared with

the dark stone of the Chapel, was dashed to splinters, young men rising

from chairs and sofa corners, buzzing and barging about the room, one

driving another against the bedroom door, which giving way, in they

fell. Then Jacob was left there, in the shallow arm-chair, alone with

Masham? Anderson? Simeon? Oh, it was Simeon. The others had all gone.

“… Julian the Apostate….” Which of them said that and the other

words murmured round it? But about midnight there sometimes rises, like

a veiled figure suddenly woken, a heavy wind; and this now flapping

through Trinity lifted unseen leaves and blurred everything. “Julian the

Apostate”—and then the wind. Up go the elm branches, out blow the

sails, the old schooners rear and plunge, the grey waves in the hot

Indian Ocean tumble sultrily, and then all falls flat again.

So, if the veiled lady stepped through the Courts of Trinity, she now

drowsed once more, all her draperies about her, her head against a

pillar.

“Somehow it seems to matter.”

The low voice was Simeon’s.

The voice was even lower that answered him. The sharp tap of a pipe on

the mantelpiece cancelled the words. And perhaps Jacob only said “hum,”

or said nothing at all. True, the words were inaudible. It was the

intimacy, a sort of spiritual suppleness, when mind prints upon mind

indelibly.

“Well, you seem to have studied the subject,” said Jacob, rising and

standing over Simeon’s chair. He balanced himself; he swayed a little.

He appeared extraordinarily happy, as if his pleasure would brim and

spill down the sides if Simeon spoke.

Simeon said nothing. Jacob remained standing. But intimacy—the room was

full of it, still, deep, like a pool. Without need of movement or speech

it rose softly and washed over everything, mollifying, kindling, and

coating the mind with the lustre of pearl, so that if you talk of a

light, of Cambridge burning, it’s not languages only. It’s Julian the

Apostate.

But Jacob moved. He murmured good-night. He went out into the court. He

buttoned his jacket across his chest. He went back to his rooms, and

being the only man who walked at that moment back to his rooms, his

footsteps rang out, his figure loomed large. Back from the Chapel, back

from the Hall, back from the Library, came the sound of his footsteps,

as if the old stone echoed with magisterial authority: “The young man—

the young man—the young man-back to his rooms.”

What’s the use of trying to read Shakespeare, especially in one of those

little thin paper editions whose pages get ruffled, or stuck together

with sea-water? Although the plays of Shakespeare had frequently been

praised, even quoted, and placed higher than the Greek, never since they

started had Jacob managed to read one through. Yet what an opportunity!

For the Scilly Isles had been sighted by Timmy Durrant lying like

mountain-tops almost a-wash in precisely the right place. His

calculations had worked perfectly, and really the sight of him sitting

there, with his hand on the tiller, rosy gilled, with a sprout of beard,

looking sternly at the stars, then at a

Comments (0)