Puppets of Faith: Theory of Communal Strife (A Critical Appraisal of Islamic faith, Indian polity) - BS Murthy (mini ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: BS Murthy

Book online «Puppets of Faith: Theory of Communal Strife (A Critical Appraisal of Islamic faith, Indian polity) - BS Murthy (mini ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author BS Murthy

So to say, with the cessation of the Kshatriya power to protect their swadharma, the Hindus would have been forced to decide whether to embrace Islam or death on offer, and probably Hindustan would have gone the Muhammadan way of Egypt, Persia, Mesopotamia, and such to its eternal hurt. Maybe, the accursed Hindu disunity, exemplified by myriad kingdoms, would have frustrated Maryam Jameelah’s Islamic cause even during Aurangzeb’s zealot mogul regime.

What if the Muslim imposters, prompted by their religious obligation, crossed the Hindu Rubicon and tried to Islamize India by force? Maybe in all probability, it would have proved counterproductive in the land of the sanātana dharma for such an Islamic tabliq would have forged the Hindu unity to the detriment of Muslim continuance in Arya Varta. As history bears witness, the policy of restraint, more so the expediency, of the Sultans, ensured an uneasy peace, in Hindustan that enabled the Sufis to spread the Islamic shadows on the peripheral swadharmas, rather unhindered. All the same, it is worth probing the causative factors that helped Islam to gain a firm foothold in Hindustan that eventually enabled it to carve out Pakistan, for its Musalmans, from what is emotionally a Hindu land.

Sadly, the Brahmans, living in the sanctified arenas of their agrahārās, were impervious to the happenings in their backyards so long as their privileged position in the polity was ensured. Whether the chandālās, living on the Hindu fringes, became Buddhists or embraced Islam, was not something to disturb the Brahman sleep, and it was this intellectual apathy of theirs that failed to foresee the demographic catastrophe in the making that the political cross of Pakistan was eventually crafted in their karma bhōmi.

Added to this was the Hindu complacency that the Muslim invaders too would eventually settle down in one of the caste corners of the pan Hindu fold for, after all, weren’t the alien intruders of yore were neatly tucked into the native caste network at some stage? All this combined to make the Hindus in general and the Brahmans in particular to pay a deaf ear to the azans of the muezzins from the masjids around, wanting the faithful to come over for the congregational prayers.

Thus it would seem that the ‘mlecĥā apathy’ of the Brahmans and the indifference of caste Hindus for the fate of the ‘outcasts’ were the contributing factors for the Islamic outreach in Hindustan as those marginalized became the easy pickings for the Islamic tabliq. Given a chance they would have readily got into the religious fold of the alien rulers as a means to assert their birth right in their coparcener land that the insensitive Hindu caste mores denied them.

Could human history get ironically better? Not even, when an African-American becomes the President of the United States, and indeed Barak Obama did become! Maybe it is this very psychic glee of the Indian Musalmans that could be behind their eagerness to see the Italian Sonia ascend the Dilli gaddi. Besides, it is a travesty of Hindustan that its media is ever at fanning this disaffection of theirs towards the Hindus so as to drive them, once again into a foreign camp, political though; what an irony!

Moreover, fortuitously for Islam, by the time the Sufi saints spread themselves out into the Indian countryside to sow the seeds of the Islamic faith in the hamlets of the untouchables; Buddhism became a spent force in Hindustan. Thus, these erstwhile Buddhists devoid of the guidance of the monks for their Nirvana could have been too eager to seek the paradise Muhammad had promised for the believers. The proposition of the Quran that the purpose of life ‘here’ is not for happiness and enjoyment as its true significance lies in its being a means to reach the ‘Hereafter’ through the Islamic straight path, could have been irresistible for the deprived outcastes of Hindustan.

Moreover, as the Hindu social mores too did not attach any value for their untouchable lives, the precepts of Hindu punar janma (rebirth) held no hope for them either in the births to follow. Oh how the psyche of Islam did sync with the deprived souls of the Indian social fringes to spread its wings, and how the Hindus, in the loss of their land, are condemned to carry the cross of their sins against their fellow humans into eternity! And that’s history.

However, the Musalman rulers’ inability to attract the elite of the land into the Islamic fold could have been two fold; for one, the Brahmans didn’t condescend to descend to suffer their Musalmanic society though some of the Rajputs, as a political expediency, kept them in good humor. And for another, either owing to their inability to rope in the Brahman ministerial talent or being intellectually apathetic towards them, and / or both, the Turkish Sultans and their Afghan minions brought in nobles from theirs, or the Persian, lands to administer their Indian fiefdoms.

So, by and large, this parochial policy of the alien rulers precluded the possibility of the native eminence to embrace Islam even for their self-promotion, and thus, the nepotism of the Musalmans and the prejudices of the caste Hindus led to a lopsided Islamic growth on the caste fringes in the Indian social setting, save some sections of the vaisyas, who opted to get under the Muhammdan banner.

Well, the vaisyas, who always felt aggrieved at being deprived of their rightful exaltation in the Hindu polity, commensurate with their wealth, were ever prone to look for the greener social pastures; first in the Buddhist fold and thereafter under the Islamic order. Moreover, their business interests would have been better served if aligned with the religion of the rulers, isn’t it?

Whatever, by and large, while the foreign nobles manned the Indian Islam, the native converts remained just that, which divide still manifests itself in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Thus, even after eight centuries of rule of the Musalman in Hindustan, and in spite of the lack of a Hindu backlash against its spread in its midst, Islam couldn’t become the majority religion in the Indian subcontinent. But still even as the Turkish rule ruined the body economy of the land, owing to the Wahabism, Islam became cancerous in the end causing the contentious partition of Hindustan.

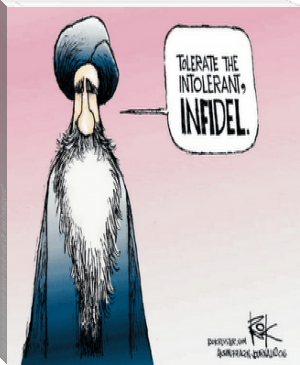

But the ‘secular’ wisdom tends to attribute Islam’s initial sustenance and its latter-day surge in Hindustan to the convenient myth of Hindu religious tolerance. While the false proposition might help embalm the never healing Hindu wounds by rationalizing their defeatist past, India’s minorities have come to decry the resurgent Hindu pride channeled through Hindutva. It’s as if they would like to deny today’s Hindus that which was denied to their forbears – pride in being themselves.

Chapter 23

Winds of Change

The Muhammadan downturn in the 18th Century that enabled the dawn of the British Raj in India turned out to be a godsend to the Hindu upswing. Historically, the parochial character of the myriad kingdoms precluded India’s Hindus from imbibing a sense of belonging to their motherland, which continues to plague the political system of the Union of India that is Bharat.

In the chequered history of Hindustan, its Rajas, and their Sāmants, who came by dime a dozen, saw their adjoining territories as pieces of real estate to be grabbed to boost up their vanity or to satiate their greed, and / or both. So, ironically, Mother India, with its splintered political dominions, would have been a no man’s land to its provincial potentates, and in later years, the Muhammadan usurpers, if anything, saw its riches as their personal endowments to cater to their pleasures and to perpetuate their memory ‘here’ forever through grandiose mausoleums, the Taj Mahal being the apogee. And that was the final nail in the coffin of the Indian economy.

The next victim of the Islamic misrule rule in India, of course, was the intellectuality, the prized possession of the Hindu civilization, nurtured from the times immemorial. With the advent of the Muslim Sultans, and the eclipse of the Hindu Rajas, short of royal patronage, the Brahman intellectual pursuits took a back seat. Besides, the overall downtrend of the Indian economy, brought about by the profligacy of the pleasure-seeking Islamic rulers, dried up the wells of charity affecting the Brahman well-being.

Moreover, their self-restrain from pursuing mundane activities, an anathema to their swadharma, contributed to the Brahman financial gloom, which eventually led to their intellectual decay as well. Hence, their collective sense of despair could have led to the feeling of dissipation that inexorably put them onto the path of laziness and prejudice. What with the Kshatriya power too on the wane, the traditional Hindu leadership remained dispirited and disjointed in the Islamic rule in India, and the Hindus, as though to seek a mass escape from life’s hardships had turned to spirituality, which further distanced them from the social realities. Whatever it may be, the undercurrents of the Hindu-Muslim coexistence in India are their bi-polar interests that even Akbar’s Din-i-Illahi failed to reconcile.

However, all that changed under the aegis of the British Raj that lasted long enough to make a difference to the Hindu self-worth, and when India celebrates its hundredth year of freedom from the British yoke in 2047, its Hindus might heartily wish ‘God bless the Great Britain’. But what could be the feelings of the Indian Musalmans towards the British, who dethroned the moguls to signal the end of the Islamic rule in Hindustan, and yet gave the parting gift of Pakistan to their faith across its borders, time only would tell. Maybe the plight of Pakistan then could shape the mind of the Indian Musalmans but one should be wary of the Muslim penchant to blame the kafirs for the Islamic ills of their own, and that of their God’s, making.

Be that as it may, the Great Britain had wide opened the Indian windows to the developed world, closed for centuries by the Brahman social prejudice and the Islamic religious bigotry, which enabled its populace, the Hindus in particular, to breathe a whiff of fresh air of contemporary Western ideas. Above all, the British lent India their English tongue that gave class to its middle class, and all this led to the advent of the cosmopolitan India. But, on the flip side, the vested interests of the ‘nation of the shopkeepers’, so as to bolster their commercial interests had ensured that whatever left of the Indian enterprise and industry was truly undermined.

Nonetheless, after their initial skepticism about the liberal ways of the British, the Hindus, led by the Brahmans, stepped out of their sanātana cocoons to explore the Western outlook, which eventually resulted in their kids embracing the English secular education in numbers. But on the other hand, the Muhammadan elite allowed themselves to be drawn into the closets of self-recrimination, and fearing religious dilution, shied away from the secular ideas and ideals, and kept their children away from the convent education. That’s how, as the Hindu masses ventured out of their caste closets, even the elite Musalmans stayed put in their mental ghettos and held on to Islam’s obscurantist tenets even more. And in this dual response to the Western cultural infusion lay the revival of the Hindu intellectuality and the beginning of the Muslim despondency.

Thus, while the Muslim dominance of India caused its stagnation, the British deliverance from the same heralded the Hindu socio-political resurgence. The emotional relief of the Hindu to be rid of the political yoke of the Musalmans, after nearly eight centuries, evoked a feel-good in the country’s majority. With the mainstay of the population, so to say, enamored of them, and they too having come to value the ancient Hindu philosophy, which got reduced to mere prejudice by then, the British loved India as best as their own interests would permit them to

Comments (0)