City at World's End - Edmond Hamilton (best classic books to read .TXT) 📗

- Author: Edmond Hamilton

- Performer: 1419156837

Book online «City at World's End - Edmond Hamilton (best classic books to read .TXT) 📗». Author Edmond Hamilton

The whole mighty past of dead Earth seemed to crush down upon Kenniston. Millions of years, trillions of lives full of pain and hope and struggle, and all for what? For this?

Carol felt it too, for she pressed closer to him. “Are they all dead, Ken? All the human race, but ourselves?”

He and Hubble had the answer for that, too, the answer they would have to give to everyone.

“There’s no reason to assume that. There may be other cities that are still inhabited. If so, we’ll soon contact them.”

She shook her head. “Words, Ken. You don’t even believe them yourself.” She drew away from him. “We’re alone,” she said. “Everything we had is gone, our world, our whole life, and we’re quite alone.”

He put his arms around her. He would have said something to comfort her, but she stood stiff and quivering, and suddenly she said,

“Ken, there are times when I can’t help hating you.”

Utterly shocked, and too bewildered to be angry yet, he let her go. He said, “Carol, you’re wrought up— hysterical—”

Her voice was low and harsh, the words came fast as though they could no longer be held back. “Am I? Maybe. But I can’t help remembering that if you and men like you hadn’t come to Middletown with that secret laboratory, fifty thousand people wouldn’t have had to suffer for it. You brought this on us…”

He began to understand now all that had been behind Carol’s taut manner and unfriendly silences, all the blind resentment that had focused upon himself.

He was for the moment furiously indignant, the more so because what she had said stung him on a sensitive nerve. He stood, almost glaring at her, and then his anger washed away, and he took her by the shoulders and said,

“Carol, you’re not making sense, and you know it! You’re bitter because you’ve lost your home, your way of life, your world, and you’re making me a scapegoat for that. You can’t! We need each other more than ever, and we’re not going to lose each other.”

She stared at him rigidly, then started to sob, and clung to him crying.

“Oh, Ken, don’t let me be a fool! I’m so mixed up, I don’t know my own mind any more.”

“All of us feel like that,” he said. “But it’ll all come right. Forget about it, Carol.”

But as he held her and soothed her and looked up past her at the alien towers and the face of the alien Moon, he knew that she could not completely forget, that that deep resentment would not die easily, and that he would have to fight it. And it would be hard to fight, for there had been the sting of truth in her words, only a partial truth but one he had not wanted ever to face.

Chapter 8— Middletown calling!

When Kenniston awoke, he lay for some time in his blankets looking around the great room, with the same feeling of unreality that he felt now each morning.

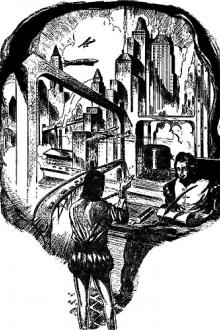

It was quite a large room, with graceful curving walls and ceiling of soft-textured, ivory plastic. But it was not as large as it looked, for the builders of the city had known how to use daringly jutting mezzanines to give two floor levels the spaciousness and loftiness of one.

He looked up at the tall, dusty windows, and wondered what this room had once been. It was part of a big structure on the plaza, for Mayor Garris had insisted that the whole Lab staff be quartered near City Hall. It had obviously been a public building, but except for a few massive tables it had been quite empty, and there was no clue to its function.

He looked around at the others on the row of mattresses. Hubble was still sleeping calmly. So was Beitz, with the slight, groaning stirrings of slumbering age. But Crisci lay wide awake and unmoving, looking up at the ceiling.

Kenniston remembered something, with a sudden pang, something that he had completely forgotten in the rush of events. He went over to Crisci, and whispered, “I’m sorry, Louis. I never thought until now about your girl.”

“Why would you think about that?” Crisci’s low voice was toneless. “Why would you, when all this has happened?” He went on, as tonelessly, “Besides, it was all over a long time ago. For millions of years now, she’s been dead.”

Kenniston lingered a moment, seeking something to say, remembering now Crisci’s eager talk of the girl he was soon to marry— the girl who lived fifty miles away from Middletown. He could find nothing to say. Crisci’s tragedy had been repeated many times among these people— the mother whose son had gone to California, the wife whose husband had been upstate on a business trip, the lovers, the families, the friends, divided forever by the great gulf of time. He felt again a great thankfulness that Carol had come through with him, and a renewed determination to hold her against anything.

Kenniston was lighting his morning cigarette, when the others rose. He paused suddenly, and said, “I just thought—”

Hubble grinned at him. “Yes, I know. You just thought about tobacco. You, and a lot of people, will soon have to do without.”

As they went out to get their breakfast at the nearest community kitchen, Hubble told him what was going forward.

“McLain’s going back to Middletown to bring gasoline engines and pumps. We have to get water flowing in the city’s system at once, and it may be a long time before we can figure out its pumping power. They seem to be atomic engines of some sort, but I’m not sure.”

“What about food rationing?”

“Food and medicine will all go into guarded warerooms. Ration tickets will be printed at once. Use of cars is forbidden, of course. Everybody is restricted to their own Ward district temporarily, to prevent accidents in exploration. We’ve already organized crews to explore the city.”

Kenniston nodded. He drew the last drags of a cigarette suddenly precious, before he spoke.

“That’s all good. But the main problem will be morale, Hubble.” He thought of Carol, as he added, “I don’t believe these people can take it, if they find out they’re the last humans left.” Hubble looked worried. “I know. But there must be people left somewhere. This city wasn’t abandoned because of sudden disaster. They may just have gone to other, better cities.”

“There wasn’t a whisper on the radio from outside Middletown,” Kenniston reminded.

“No. But I believe they used something different from our radio system. That’s what I want you for this morning, Ken. Beitz last night found a communication system in a building near here. It has big apparatus that he thinks was for televisor communication. That’s more in your field than ours.”

Kenniston felt a sharp interest, the interest of the technician that not even world’s end could completely kill. “I’d like to see that.”

As they walked through the cold red morning, Kenniston was surprised by the unexpectedly everyday appearance of this alien city beneath the dome.

Families were trooping toward the community kitchens, with the air of going on picnic. A little band of children whooped down the nearest street, a small, woolly dog racing beside them with frantic barking. A bald, red-faced man in undershirt and trousers smoked his pipe and looked down the mighty street with mild curiosity. Two plump women, one of whom was buttoning a reluctant small boy into his jacket, called to each other from neighboring doorways.

“— and they say that Mrs. Biler’s feeling better now, but her husband’s still poorly—”

“Human beings,” said Hubble, “are adaptable. Thank God for that.”

“But if they’re the last? They won’t be able to adapt to that.”

Hubble shook his head. “No. I’m afraid not.”

After breakfast, Beitz led them to a big square building two blocks off the plaza. Inside was a large, shadowy hall, in which bulked a row of tall, square blocks of apparatus. They were, obviously, televisor instruments. Each had a square screen, a microphone grating, and beneath that a panel of control switches, pointer dials, and other less identifiable instruments.

Kenniston found and opened a service panel in the back of one. Brief examination of the tangled apparatus inside discouraged him badly.

“They were televisor communication instruments, yes. But the principles on which they worked are baffling. They didn’t even use vacuum tubes— they’d apparently got beyond the vacuum tube.”

“Could you start one of them transmitting again?”

Kenniston shook his head. “The video system is absolutely beyond me. No resemblance at all to our primitive television apparatus.”

Hubble asked, “Would it be possible then to use just the audio system— use one of them as a straight sound-radio transmitter?”

Kenniston hesitated. “That might be done. It’d be mostly groping in the dark. But there are some familiar bits of design—” He pondered, then said, “The power leads come from outside. See anything around here that looks like a power station?”

Old Beitz nodded. “Only a block away. Big, shielded atomic turbines of some kind, coupled to generators.”

“We might spend years trying to learn how to operate their atomic machinery,” Kenniston said.

“We could couple gasoline engines to those generators,” Hubble suggested. “It’d furnish power enough to try one of these transmitters.”

Kenniston looked at him. “To call to the other people still left on Earth?”

“Yes. If there are any of them, they’d not hear our kind of radio calls. But this is their own communication setup. They’d hear it.”

Kenniston said finally, “All right Give me power, and I’ll try.”

In the next few days, Kenniston was so immersed in the overmastering fascination of the technical problem set him, that he saw little of how Middletown’s people were adapting to New Middletown. He could hear the trucks rumbling constantly under the dome, as McLain indefatigably pushed the work of bringing supplies from the deserted town beyond the ridge.

They brought the gasoline engines needed, not only to pump water from the great reservoirs but also to turn one of the generators in the power station. Once he had power, Kenniston began to experiment. Realizing the futility of trying to fathom the principles of the strange super-radio transmitters, he tried merely to deduce the ordinary method of operating them.

The trucks brought other things— more food, clothing, furniture, hospital equipment, books. McLain began to talk of organizing a motor expedition to explore the surrounding country. And meanwhile, the crews already organized to explore New Middletown itself were searching every block and building. Already, they had made two surprising discoveries.

Hubble took Kenniston away from his work to see one of these. He led down through a chain of corridors and catacombs underneath the city.

“You know that it’s a few degrees warmer here in New Middletown than the Sun’s retained heat can account for,” Hubble said. “We found big conduits that seem to bring that slightly wanner air up into the city, so I had the men trace the conduits down to their source.”

Kenniston felt sudden excitement. “The source? A big artificial heating plant?”

“No, not that,” Hubble said. “But here we are now. Have a look for yourself.”

They had suddenly emerged onto a railed gallery in a vast underground chamber. The narrow gallery was the brink of an abysmal pit— a great, circular shaft that dropped into unplumbed blackness. Kenniston stared puzzledly. He saw that big conduits led upward out of the pit, and then diverged in all directions. “The slightly warmer air comes up from this shaft,” Hubble said, nodding toward the pit. He added, “I know it sounds impossible, to our engineering experience. But I

Comments (0)