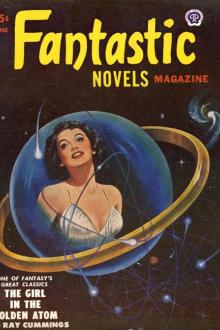

The Girl in the Golden Atom - Raymond King Cummings (good summer reads TXT) 📗

- Author: Raymond King Cummings

- Performer: -

Book online «The Girl in the Golden Atom - Raymond King Cummings (good summer reads TXT) 📗». Author Raymond King Cummings

"'If our country is at war at the time you read this, your duty is plain. I have no fears regarding your course of action. But if not, I do not care to influence unduly your decision about venturing into this unknown other world. The danger into which I personally may have fallen must count for little with you, in a decision to hazard your own lives. I may point out, however, that such a journey successfully accomplished cannot fail but be the greatest contribution to science that has ever been made. Nor can I doubt but that your coming may prove of tremendous benefit to the humanity of this other equally important, though, in our eyes, infinitesimal world.

"'I therefore suggest, gentlemen, that you start your journey into the ring at 8 P. M. on the evening of November 4, 1923. You will do your best to find your way direct to the city of Arite, where, if I am alive, I will be awaiting you.'"

CHAPTER X TESTING THE DRUGSThe Doctor laid his papers on the table and looked up into the white faces of the three men facing him. "That's all, gentlemen," he said.

For a moment no one spoke, and on the face of each was plainly written the evidence of an emotion too deep for words. The Doctor sorted out the papers in silence, glanced over them for a moment, and then reached for a large metal ash tray that stood near him on the table. Taking a match from his pocket he calmly lighted a corner of the papers and dropped them burning into the metal bowl. His friends watched him in awed silence; only the Very Young Man found words to protest.

"Say now, wait," he began, "why——"

The Doctor looked at him. "The letter requests me to do that," he said.

"But I say, the formulas——" persisted the Very Young Man, looking wildly at the burning papers.

The Doctor held up one of the white tin boxes lying on the arm of his chair.

"In these tins," he said, "I have vials containing the specified quantity of each drug. It is ample for our purpose. I have done my best to memorize the formulas. But in any event, I was directed to burn them at the time of reading you the letter. I have done so."

The Big Business Man came out of a brown study.

"Just three weeks from to-night," he murmured, "three weeks from to-night. It's too big to realize."

The Doctor put the two boxes on the table, turned his chair back toward the others, and lighted a cigar.

"Gentlemen, let us go over this matter thoroughly," he began. "We have a momentous decision to make. Either we destroy those boxes and their contents, or three weeks from to-night some or all of us start our journey into the ring. I have had a month to think this matter over; I have made my decision.

"I know there is much for you to consider, before you can each of you choose your course of action. It is not my desire or intention to influence you one way or the other. But we can, if you wish, discuss the matter here to-night; or we can wait, if you prefer, until each of you has had time to think it out for himself."

"I'm going," the Very Young Man burst out.

His hands were gripping the arms of his chair tightly; his face was very pale, but his eyes sparkled.

The Doctor turned to him gravely.

"Your life is at stake, my boy," he said, "this is not a matter for impulse."

"I'm going whether any one else does or not," persisted the Very Young Man. "You can't stop me, either," he added doggedly. "That letter said——"

The Doctor smiled at the youth's earnestness. Then abruptly he held out his hand.

"There is no use my holding back my own decision. I am going to attempt the trip. And since, as you say, I cannot stop you from going," he added with a twinkle, "that makes two of us."

They shook hands. The Very Young Man lighted a cigarette, and began pacing up and down the room, staring hard at the floor.

"I can remember trying to imagine how I would feel," began the Big Business Man slowly, "if Rogers had asked me to go with him when he first went into the ring. It is not a new idea to me, for I have thought about it many times in the abstract, during the past five years. But now that I am face to face with it in reality, it sort of——" He broke off, and smiled helplessly around at his companions.

The Very Young Man stopped in his walk. "Aw, come on in," he began, "the——"

"Shut up," growled the Banker, speaking for the first time in many minutes.

"I'm sure we would all like to go," said the Doctor. "The point is, which of us are best fitted for the trip."

"None of us are married," put in the Very Young Man.

"I've been thinking——" began the Banker. "Suppose we get into the ring—how long would we be gone, do you suppose?"

"Who can say?" answered the Doctor smiling. "Perhaps a month—a year—many years possibly. That is one of the hazards of the venture."

The Banker went on thoughtfully. "Do you remember that argument we had with Rogers about time? Time goes twice as fast, didn't he say, in that other world?"

"Two and a half times faster, if I remember rightly, he estimated," replied the Doctor.

The Banker looked at his skinny hands a moment. "I owned up to sixty-four once," he said quizzically. "Two years and a half in one year. No, I guess I'll let you young fellows tackle that; I'll stay here in this world where things don't move so fast."

"Somebody's got to stay," said the Very Young Man. "By golly, you know if we're all going into that ring it would be pretty sad to have anything happen to it while we were gone."

"That's so," said the Banker, looking relieved. "I never thought of that."

"One of us should stay at least," said the Doctor. "We cannot take any outsider into our confidence. One of us must watch the others go, and then take the ring back to its place in the Museum. We will be gone too long a time for one person to watch it here."

The Very Young Man suddenly went to one of the doors and locked it.

"We don't want any one coming in," he explained as he crossed the room and locked the others.

"And another thing," he went on, coming back to the table. "When I saw the ring at the Biological Society the other day, I happened to think, suppose Rogers was to come out on the underneath side? It was lying flat, you know, just as it is now." He pointed to where the ring lay on the handkerchief before them. "I meant to speak to you about it," he added.

"I thought of that," said the Doctor. "When I had that case built to bring the ring here, you notice I raised it above the bottom a little, holding it suspended in that wire frame."

"We'd better fix up something like that at the Museum, too," said the Very Young Man, and went back to his walk.

The Big Business Man had been busily jotting down figures on the back of an envelope. "I can be in shape to go in three weeks," he said suddenly.

"Bully for you," said the Very Young Man. "Then it's all settled." The Big Business Man went back to his notes.

"I knew what your answer would be," said the Doctor. "My patients can go to the devil. This is too big a thing."

The Very Young Man picked up one of the tin boxes. "Tell us how you made the powders," he suggested.

The Doctor took the two boxes and opened them. Inside each were a number of tiny glass vials. Those in one box were of blue glass; those in the other were red.

"These vials," said the Doctor, "contain tiny pellets of the completed drug. That for diminishing size I have put in the red vials; those of blue are the other drug.

"I had rather a difficult time making them—that is, compared to what I anticipated. Most of the chemicals I bought without difficulty. But when I came to compound those two myself"—the Doctor smiled—"I used to think I was a fair chemist in my student days. But now—well, at least I got the results, but only because I have been working almost night and day for the past month. And I found myself with a remarkably complete experimental laboratory when I finished," he added. "That was yesterday; I spent nearly all last night destroying the apparatus, as soon as I found that the drugs had been properly made."

"They do work?" said the Very Young Man anxiously.

"They work," answered the Doctor. "I tried them both very carefully."

"On yourself?" said the Big Business Man.

"No, I didn't think that necessary. I used several insects."

"Let's try them now," suggested the Very Young Man eagerly.

"Not the big one," said the Banker. "Once was enough for that."

"All right," the Doctor laughed. "We'll try the other if you like."

The Big Business Man looked around the room. "There's a few flies around here if we can catch one," he suggested.

"I'll bet there's a cockroach in the kitchen," said the Very Young Man, jumping up.

The Doctor took a brass check from his pocket. "I thought probably you'd want to try them out. Will you get that box from the check-room?" He handed the check to the Very Young Man, who hurried out of the room. He returned in a moment, gingerly carrying a cardboard box with holes perforated in the top. The Doctor took the box and lifted the lid carefully. Inside, the box was partitioned into two compartments. In one compartment were three little lizards about four inches long; in the other were two brown sparrows. The Doctor took out one of the sparrows and replaced the cover.

"Fine," said the Very Young Man with enthusiasm.

The Doctor reached for the boxes of chemicals.

"Not the big one," said the Banker again, apprehensively.

"Hold him, will you," the Doctor said.

The Very Young Man took the sparrow in his hands.

"Now," continued the Doctor, "what we need is a plate and a little water."

"There's a tray," said the Very Young Man, pointing with his hands holding the sparrow.

The Doctor took a spoon from the tray and put a little water in it. Then he took one of the tiny pellets from a red vial and crushing it in his fingers, sprinkled a few grains into that water.

"Hold that a moment, please." The Big Business Man took the proffered spoon.

Then the Doctor produced from his pocket a magnifying glass and a tiny pair of silver callipers such as are used by jewelers for handling small objects.

"What's the idea?" the Very Young Man wanted to know.

"I thought I'd try and put him on the ring," explained the Doctor. "Now, then hold open his beak."

The Very Young Man did so, and the Doctor poured the water down the bird's throat. Most of it spilled; the sparrow twisted its head violently, but evidently some of the liquid had gone down the bird's throat.

Silence followed, broken after a moment by the scared voice of the Very Young Man. "He's getting smaller, I can feel him. He's getting smaller."

"Hold on to him," cautioned the Doctor. "Bring him over here." They went over to the table by the ring, the Banker and the Big Business Man standing close beside them.

"Suppose he tries to fly when we let go of him," suggested the Very Young Man almost in a whisper.

"He'll probably be too confused," answered the Doctor. "Have you got him?" The sparrow was hardly bigger than a large horse-fly now, and the Very Young

Comments (0)