City at World's End - Edmond Hamilton (best classic books to read .TXT) 📗

- Author: Edmond Hamilton

- Performer: 1419156837

Book online «City at World's End - Edmond Hamilton (best classic books to read .TXT) 📗». Author Edmond Hamilton

His voice trailed off. The five pairs of alien eyes regarded him, the five alien bodies breathed and stirred, and the crest of white fur on the proud one’s skull lifted in a way so beastlike that it was impossible for Kenniston to pretend any longer to accept them as human. Doubt, distrust, and just a hint of fear crept into his face. Piers Eglin frowned a little, and started to speak.

With the suddenness of a bat darting out in the evening, one of the lean dark brothers whipped wide his wings and made a little spring at Kenniston, uttering a cry that sounded very much like “Boo!”

Kenniston leaped backward, startled almost out of his skin. And the lean one promptly doubled up with laughter, which was echoed by the others. Even the large grey creature smiled. They all looked at Kenniston and laughed, and presently Hubble got it and began to laugh too, and after that there was nothing for Kenniston to do but join in. The joke was on him, at that. They had known perfectly well how he felt about them, and the lean one had paid him back in his own coin, but with humor and not malice.

And somehow, after they had laughed together, the tension was gone. Laughter is a human sort of thing. Kenniston mumbled something, and Gorr Holl slapped his shoulder, nearly putting him on his face.

But when he approached the dusty generators, Gorr Holl changed abruptly from a shambling, good-natured creature into a highly efficient technician. He operated hidden catches, and had a shield panel off one of the big mechanisms before Kenniston saw how he did it. He drew a flat pocket flash from a pouch on his harness, and used it for light as he poked his hairy bullet-shaped head inside the machine. His low, rumbling comments came out of the bowels of the generator. Finally Gorr Holl withdrew his head from the machine, and spoke disgustedly.

Eglin translated, “He says this old installation is badly designed and in poor condition. He says he would like to get his hands on the technician who would do a job like this.”

Kenniston laughed again. The big, furry Capellan sounded like a blood brother to every repair technician on old Earth. While Gorr Holl examined the other generators, Piers Eglin fastened onto Hubble and Kenniston, deluging them with questions about their own remote time. They managed at last to ask a question of their own, one that was big in their minds but that they’d had no chance to ask before.

“Why is Earth lifeless now? What happened to all its people?”

Piers Eglin said, “Long ago, Earth’s people went out to other worlds. Not so much to the other planets of this System— the outer ones were cold, and watery Venus had too small a land surface— but to the worlds of other stars, across the galaxy.”

“But surely some of them would have stayed on Earth?” said Kenniston.

Eglin shrugged. “They did, until it grew so cold that even in these domed cities life was difficult. Then the last of them went, to the worlds of warmer Suns.”

Kenniston said, “In our day, we hadn’t even reached the Moon.” He felt a little dazed by it all. “…to the worlds of other stars, across the galaxy…”

Gorr Holl finally came back to them and rumbled lengthily. Eglin translated, “He thinks they can get the generators going. But it’ll take time, and he’ll need materials— copper, magnesium, some platinum—”

They listened carefully, and Hubble nodded and said, “We can get all those for you in old Middletown.”

“The old city?” cried Piers Eglin eagerly. “I will go with you! Let us start at once!”

The little historian was afire for a look at the old town. He fidgeted until he and Hubble and Kenniston, in a jeep; were driving across the cold ocher wasteland.

“I shall see, with my own eyes, a town of the pre-atomic age!” he exulted.

It was strange to come upon old Middletown, standing so silent in the midst of desolation. The houses were as he had last seen them, the doors locked, the empty porch swings rocking in the cold wind. The streets were drifted thick with dust. The trees were bare, and the last small blade of grass had died.

Kenniston saw that Hubble’s eyes were misted, and his own heart contracted with a terrible pang of longing. He wished that he had not come. Back in that other city, absorbed in the effort to survive, one could almost forget that there had been a life before.

He drove the jeep through those deathly streets, and memory spoke to him strongly of lost summers— girls in bright frocks, catalpa trees heavy with blossom, the quarreling of wrens, and the lights and sounds of human voices in the drowsy evening. Piers Eglin was speechless with joy, lost in a historian’s dream as he walked the streets and looked into shops and houses.

“It must be preserved,” Eglin whispered. “It is too precious. I will have them build a dome and seal it all— the signs, the artifacts, the beautiful scraps of paper!”

Hubble said abruptly, “There’s someone here ahead of us.” Kenniston saw the small bullet-shaped car that stood outside the old Lab. Out of the building came Norden Lund and Varn Allan.

She spoke to Eglin, and he translated, “They have been gathering data for her report to Government Center.”

Kenniston saw the distaste in the woman’s clearcut face as her blue eyes rested on the panorama of grimy mills, the towering stacks black with forgotten smokes, the rustling rails of the sidings, the drab little houses huddled along the narrow streets. He resented it, and said defiantly. “Ask her what she thinks of our little city?”

Eglin did, and Varn Allan answered incisively. The little historian looked uneasy when Kenniston asked him to interpret.

“Varn Allan says that it is unbelievable people could live in a place so pitiful and sordid.”

Lund laughed. Kenniston flushed hot, and for a moment he detested this woman for her cool, imperious superiority. She looked at old Middletown as one might look at an unclean apes’ den.

Hubble saw his face, and laid a hand on his arm. “Come on, Ken. We have work to do.”

He followed the older man into the Lab, Piers Eglin trailing along. He said, “Why the hell would they put a haughty blonde in authority?”

Hubble said, “Presumably because she is competent to fill the job. Don’t tell me old-fashioned masculine vanity is bothering you?”

Piers Eglin had understood what they were saying, for he chuckled. “That’s not such an old-fashioned feeling. Norden Lund doesn’t much like being Sub for a girl.”

When they came out of the building with the materials Gorr Holl had requested, Varn Allan and Lund were gone.

They found, upon their return to New Middletown, that Gorr Holl and his crew were already at work disassembling the generators. Bellowing orders, thundering deep-chested Capellan profanity, attacking each generator as though it were a personal enemy, Gorr Holl drove his hard-handed spacemen into performing miracles of effort.

Kenniston, in the days that followed, forgot all sense of strangeness in the intense technical interest of the work. Laboring as he could, eating and sleeping with these star-worlders though the long days and nights, he began to pick up the language with amazing speed. Piers Eglin was eager to help him, and after Kenniston discovered that the basic structure of the tongue was that of his own English, things went more easily.

He discovered one day that he was working beside the humanoids as naturally as though he had always done it. It no longer seemed strange that Magro, the handsome white-furred Spican, was an electronics expert whose easy unerring work left Kenniston staring.

The brothers, Ban and Bal, were masters at refitting. Kenniston envied their deftness with outworn parts, the swift ease with which their wiry bodies flitted batlike among the upper levels of the towering machines, where it was hard for men to go.

And Lal’lor, the old grey stodgy one of the massive body, who spoke little but saw much from wise little eyes, had an amazing mathematical genius. Kenniston discovered it when Lal’lor went with him and Hubble and Piers Eglin to look at the big heat shaft that seemed to go down to the bowels of Earth.

The historian nodded comprehendingly as he looked at the great shaft and its conduits. It descended, he said, to Earth’s inmost core.

“It was a great work. It and others like it, in these domed cities, kept Earth habitable ages longer than would otherwise have been the case. But there is no more heat in Earth’s core to tap, now.” He sighed. “The doom of all planets, sooner or later. Even after their Sun has waned they can live while their interior heat keeps them warm. But when that interior planetary heat dies the planet must be abandoned.”

Lal’lor spoke in his throaty, husky voice. “But Jon Arnol, as you know, claims that a dead, cold planet can be revived. And his equations seem unassailable.”

And the bulk gray Miran— for that star had bred him, Kenniston had learned— repeated a staggering series of equations that Kenniston could not even begin to follow.

Piers Eglin, for some reason, looked oddly uncomfortable. He seemed to avoid Lal’lor’s gaze as he said hastily, “Jon Arnol is an enthusiast, a fanatic theorist. You know what happened when he tried a test.”

As soon as Kenniston could make himself understood in the new tongue, Piers Eglin considered that his duty was done and he departed for Old Middletown, to shiver and freeze and root joyfully among the archaic treasures that abounded in every block. Left alone with the star-worlders, Kenniston found himself more and more forgetting differences of time and culture and race as he worked with them to force life back into the veins of the city.

They had New Middletown’s water system in full operation again, and the luxury of opening one of the curious taps and seeing water gush forth in endless quantities was a wonderful thing. Many of the great atomic generators were functioning now, including a tremendous auxiliary heating system which made the air inside the dome several degrees warmer. And Gorr Holl and Margo had been working hard on the last miracle of all.

There came a night when the big Capellan called Kenniston into one of the main generator rooms. Magro and a number of the crewmen were there, smeared with dust and grease but grinning the happy grins of men who have just seen the last of a hard job. Gorr Holl pointed to a window.

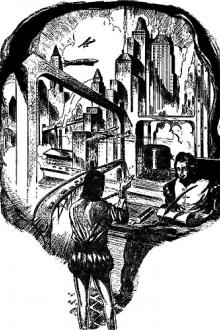

“Stand over there,” he said to Kenniston, “and watch.” Kenniston looked out, over the dark city. There was no moon, and the towers were cloaked in shadow, the black canyons of the streets below them pricked here and there with the feeble glints of candles and the few electric bulbs that shone around the City Hall. Gorr Holl strode across the room behind him, to a huge control panel half the height of the wall. He grunted. There was a click and a snap as the master switch went home, and suddenly, over that nighted city under the dome, there burst a brilliant flood of light.

The shadowy towers lit to a soaring glow. The streets became rivers of white radiance, soft and clear, and above it all there was an new night sky— the wondrous luminescence of the dome, like a vast bowl fashioned out of moonbeams and many-colored clouds, crowning the gleaming towers with a glory of its own. It was so strange and beautiful, after the long darkness and the shadows, that Kenniston stood without moving, looking at the miracle of light, and

Comments (0)