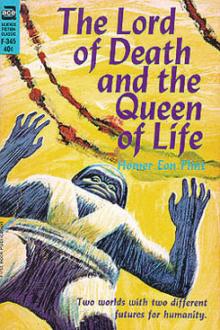

The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life - Homer Eon Flint (online e book reading txt) 📗

- Author: Homer Eon Flint

- Performer: -

Book online «The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life - Homer Eon Flint (online e book reading txt) 📗». Author Homer Eon Flint

“I see,” said Van Emmon, thoughtfully. “You have no rain.”

“Precisely”—from Estra. “We have the air completely under our control. We give our vegetation artificial showers when we think it should have it, not when nature wills; and similarly we use electricity instead of sunlight that we may stimulate its growth.”

“In short”—Van Emmon put it as the car slid slowly down the remaining distance—“in short, you have abolished the weather.”

The Venusian nodded. “And I’ll save you the trouble of suggesting,” he added, “that we are nothing more nor less than hothouse people!”

V THE HUMAN CONSERVATORY“But there is this difference,” he cautioned as they stepped out of the elevator into a sort of a plaza, “that, whereas you people on the earth have only begun to use the hothouse principle, we here have perfected it.

“I suggest that you waste no time looking for faults.”

Van Emmon stared at the doctor. “How does this idea fit your theory, Kinney—that Venus is simply the earth plus several thousand extra generations of civilization?”

“Fit?” echoed the doctor. “Fits like a glove. We humans are fast becoming a race of indoor-people despite all the various “back-to- nature” movements. Look at the popularity of inclosed automobiles, for example.

“The only thing that surprises me”—turning to their guide—“is that you use your legs for their original purpose.”

Estra smiled, and pointed out something standing a few feet away. It was a small, shuttle-shaped aircraft, with clear glass sides which had actually made them overlook it at first. Peering closer they saw that the plaza and surrounding streets were nearly filled with these all but invisible cars.

The Venusian explained. “You marvel that I use my legs and walk the same as you do. I am glad you have brought up this point, because it is a fact that our people use mechanisms instead of bodily energy, almost altogether. These cars you see are universally used for transportation. I am one of the very few who appreciate the value of natural exercise.”

“Do you mean to say,” demanded Van Emmon, “that the average Venusian does no walking?”

“Not a mile a year,” said Estra gravely.

“Just what he is obliged to do indoors from room to room.” And he involuntarily glanced down at his own extremely thin legs.

The architect’s eyes widened with a growing understanding. “I see now,” she murmured. “That’s why there was no one else to greet us.”

The Venusian smiled gratefully. “We thought it best. You’d have been shocked outright, I am sure, had you been introduced to a representative Venusian without any explanation.”

They fell silent. Still, without moving from the point where they had left the elevator, the four from the earth examined the surrounding buildings in a renewed effort to see some system in their arrangement. Directly in front of them was a particularly large structure. Like all the rest, it was of hopelessly irregular design, yet it had a large domed central portion which gave it the appearance of an auditorium; and the effect was further borne out by a subdued humming sound which seemed to come from it.

Smith asked Estra if it were a hall.

“Yes and no,” was the answer. “It fills the purpose of a hall, but is not built on the hall plan.” And Smith tried to stare through the translucent walls of the thing.

The other buildings within immediate reach were of every possible appearance. Some would have passed for cottages, others for stores, still others for the most fanciful of studios. And nowhere was there such a thing as a sign, even at the street corners, much less on a building.

“Not that we would be able to read your signs, if you had them,” commented the doctor, “but I’d like to know how your people find their way without something of that kind to guide them.”

Estra’s smile did not change. “That is something you will understand better before long,” said he, “provided you feel ready to explore a little further.”

The four looked at each other in question, and suddenly it struck them all that they were a rather pugnacious-looking crew in their cumbersome suits of armor and formidable helmets. The doctor turned to Estra.

“You ought to know”—he appealed—“whether we can take off these suits now.”

“It would be best,” was the reply. “You will find the air and temperature decidedly more warm and moist than what you have been used to, but otherwise practically the same. There is a slightly larger proportion of oxygen; that is all. Just imagine you are in a hothouse.”

Smith and the doctor were already discarding their suits. Van Emmon and Billie followed more slowly; the one, because he did not share the doctor’s confidence in their guide; the other, because of a sudden shyness in his presence. The Venusian noted this.

“You need not feel any embarrassment,” said he to Billie’s vast astonishment. “There is no distinction here between the dress of the two sexes.” And again all four marveled that he should know so much about them.

Once out of the armor the visitors felt much more at ease. The slightly reduced gravitation gave them a sense of lightness and freedom which more than balanced the junglelike oppressiveness of the air. They found themselves guarding against a certain exuberance; perhaps it was the extra oxygen, too.

They strode toward the large structure directly ahead. At its entrance— a wide, square portal which opened into a fan-shaped lobby—Estra paused and smiled apologetically—as he mopped his forehead and upper lip with a paper handkerchief, which he immediately dropped into a small, trap-covered opening in the wall at his side.

These little doors, by the way, were to be seen at frequent intervals wherever they went. Incidentally not a scrap of paper or other refuse was to be noted anywhere—streets and all were spotless.

As for Estra—“I am not accustomed to moving at such speed,” he explained his discomfort. “If you do not mind, please walk a little more leisurely.”

They took their time about passing through this lobby. For one thing, Estra said there would have to be a small delay; and for another, the walls and ceilings of the space were most remarkably ornamented. They were fairly covered with what appeared, at first glance, to be absolutely lifelike paintings and sculptures. They were so arranged as to strengthen the structural lines of the place, and, of course, they were of more interest to Billie than to the others. [Footnote: The specialist in architecture and related subjects is referred to E. Williams Jackson’s report to the A.I.A., for details of these basrelief photographs.]

Desiring to examine some of the work far overhead, Billie clambered up on a convenient pedestal in order to look more closely. She took the strength of things for granted, and put her weight too heavily on a molding on the edge of the pedestal; with the result that there was a sharp crack; and the girl struck the floor in a heap. She got to her feet before Van Emmon could reach her side, but her face was white with pain.

“Sprained—ankle,” said she between set lips, and proceeded to stump up and down the lobby, “to limber up,” as she said, although her three companions offered to do anything that might relieve her.

To the surprise of all, Estra leaned against a pillar and watched the whole affair with perfect composure. He made no offer of help, said nothing whatever in sympathy. In a moment he noticed the looks they gave him—their stares.

“I must beg your pardon,” he said, still smiling. “I am sorry this happened; it will not be easy to explain.

“But you will find all Venusians very unsympathetic. Not that we are hard hearted, but because we simply lost the power of sympathy.

“We do not know what pity is. We have eliminated everything that is disagreeable, all that is painful, from our lives to such an extent that there is never any cause for pity.”

The three young people could say nothing in answer. The doctor, however, spoke thoughtfully:

“Perhaps it is superfluous; but—tell me—have you done away with injustice, Estra?”

“That is just the point,” agreed the Venusian. “Justice took the place of pity and mercy; it was so long ago I am barely able to appreciate your own views on the subject.”

Billie, her ankle somewhat better, turned to examine other work; but at the moment another Venusian approached from the upper end of the lobby. Walking slowly, he carried four small parcels with a great deal of effort, and the explorers had time to scrutinize him closely.

He was built much like Estra, but shorter, and with a little more flesh about the torso. His forehead bulged directly over his eyes, instead of above his ears, as did Estra’s; also his eyes were smaller and not as far apart. His whole expression was equally kind and affable, despite a curiously shriveled appearance of his lips; they made the front of his mouth quite flat, and served to take attention away from his pitifully thin legs.

Estra greeted him with a cheery phrase, in a language decidedly different from any the explorers were familiar with. In a way, it was Spanish, or, rather, the pure Castilian tongue; but it seemed to be devoid of dental consonants. It was very agreeable to listen to.

Estra, however, had taken the four parcels from his comrade, and now presented him to the four, saying that his name was Kalara, and that he was a machinist. “He cannot use your tongue,” said the Venusian. “Few of us have mastered it. There are difficulties.

“As for these machines”—unwrapping the parcels—“I must apologize in advance for certain defects in their design. I invented them under pressure, so to speak, having to perfect the whole idea in the rather short time that has elapsed since you, doctor, began the sky-car.”

“And what is the purpose of the machines?” from Billie, as she was about to accept the first of the devices from the Venusian.

For some reason he appeared to be especially interested in the girl, and addressed half of his remarks to her; and it was while his smiling gaze was fixed upon her eyes that he gave the answer:

“They are to serve”—very carefully—“partly as lexicons and partly as grammars. In short, they are mechanical interpreters.”

VI THE TRANSLATING MACHINES“First, let me remind you,” said the Venusian, “of our lack of certain elements that you are familiar with on the Earth. We have never been able to improve on the common telephone. That is why we must still assemble in person whenever we have any collective activity; while on the Earth the time will come when your wireless principle will be developed to the point of transmitting both light and sound; and after that there will be little need of gatherings of any sort.”

Then he explained the apparatus. It consisted of a miniature head-telephone, connected to a small, metallic case the size of a cigar-box, the cover of which was a transparent diaphragm. Estra did not open the case, but showed the mechanism through the cover.

“Essentially, this is a ‘word-for-word’ device,” said he, pointing to a swiftly revolving dial within the box. “On one face of that dial are some ten thousand word-images, made by vibration, after the phonograph

Comments (0)