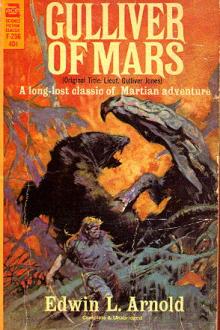

Gulliver of Mars - Edwin Lester Linden Arnold (great novels of all time txt) 📗

- Author: Edwin Lester Linden Arnold

- Performer: -

Book online «Gulliver of Mars - Edwin Lester Linden Arnold (great novels of all time txt) 📗». Author Edwin Lester Linden Arnold

For twenty minutes Fate played with me, and then the deadly suck of the stream got me down again close to where the water began to race for the falls. I vowed savagely I would not go over them if it could be helped, and struggled furiously.

On the left, in shadow, a narrow beach seemed to lie between the water and the cliff foot; towards it I fought. At the very first stroke I fouled a raft; the occupant thereof came tumbling aboard and nearly swamped me. But now it was a fight for life, so him I seized without ceremony by clammy neck and leg and threw back into the water. Then another playful Martian butted the behind part of my canoe and set it spinning, so that all the stars seemed to be dancing giddily in the sky. With a yell I shoved him off, but only to find his comrades were closing round me in a solid ring as we sucked down to the abyss at ever-increasing speed.

Then I fought like a fury, hacking, pushing, and paddling shorewards, crying out in my excitement, and spinning and bumping and twisting ever downwards. For every foot I gained they pushed me on a yard, as though determined their fate should be mine also.

They crowded round me in a compact circle, their poor flower-girt heads nodding as the swift current curtsied their crafts. They hemmed me in with desperate persistency as we spun through the ghostly starlight in a swirling mass down to destruction! And in a minute we were so close to the edge of the fall I could see the water break into ridges as it felt the solid bottom give way under it. We were so close that already the foremost rafts, ten yards ahead, were tipping and their occupants one by one waving their arms about and tumbling from their funeral chairs as they shot into the spray veil and went out of sight under a faint rainbow that was arched over there, the symbol of peace and the only lovely thing in that gruesome region. Another minute and I must have gone with them. It was too late to think of getting out of the tangle then; the water behind was heavy with trailing silks and flowers. We were jammed together almost like one huge float and in that latter fact lay my one chance.

On the left was a low ledge of rocks leading back to the narrow beach already mentioned, and the ledge came out to within a few feet of where the outmost boat on that side would pass it. It was the only chance and a poor one, but already the first rank of my fleet was trembling on the brink, and without stopping to weigh matters I bounded off my own canoe on to the raft alongside, which rocked with my weight like a tea-tray. From that I leapt, with such hearty good-will as I had never had before, on to a second and third. I jumped from the footstool of one Martian to the knee of another, steadying myself by a free use of their nodding heads as I passed. And every time I jumped a ship collapsed behind me. As I staggered with my spring into the last and outermost boat the ledge was still six feet away, half hidden in a smother of foam, and the rim of the great fall just under it. Then I drew all my sailor agility together and just as the little vessel was going bow up over the edge I leapt from her—came down blinded with spray on the ledge, rolled over and over, clutched frantically at the frozen soil, and was safe for the moment, but only a few inches from the vortex below!

As soon as I picked myself up and got breath, I walked shorewards and found, with great satisfaction, that the ledge joined the shelving beach, and so walked on in the blue obscurity of the cliff shadow back from the falls in the bare hope that the beach might lead by some way into the gully through which we had come and open country beyond. But after a couple of hundred yards this hope ended as abruptly as the spit itself in deep water, and there I was, as far as the darkness would allow me to ascertain, as utterly trapped as any mortal could be.

I will not dwell on the next few minutes, for no one likes to acknowledge that he has been unmanned even for a space. When those minutes were over calmness and consideration returned, and I was able to look about.

All the opposite cliffs, rising sheer from the water, were in light, their cold blue and white surfaces rising far up into the black starfields overhead. Looking at them intently from this vantage-point I saw without at first understanding that along them horizontally, tier above tier, were rows of objects, like—like—why, good Heavens, they were like men and women in all sorts of strange postures and positions! Rubbing my eyes and looking again I perceived with a start and a strange creepy feeling down my back that they WERE men and women!—hundreds of them, thousands, all in rows as cormorants stand upon seaside cliffs, myriads and myriads now I looked about, in every conceivable pose and attitude but never a sound, never a movement amongst the vast concourse.

Then I turned back to the cliffs behind me. Yes! they ere there too, dimmer by reason of the shadows, but there for certain, from the snowfields far above down, down—good Heavens! to the very level where I stood. There was one of them not ten yards away half in and half out of the ice wall, and setting my teeth I walked over and examined him. And there was another further in behind as I peered into the clear blue depth, another behind that one, another behind him—just like cherries in a jelly.

It was startling and almost incredible, yet so many wonderful things had happened of late that wonders were losing their sharpness, and I was soon examining the cliff almost as coolly as though it were only some trivial geological “section,” some new kind of petrified sea-urchins which had caught my attention and not a whole nation in ice, a huge amphitheatre of fossilised humanity which stared down on me.

The matter was simple enough when you came to look at it with philosophy. The Martians had sent their dead down here for many thousand years and as they came they were frozen in, the bands and zones in which they sat indicating perhaps alternating seasons. Then after Nature had been storing them like that for long ages some upheaval happened, and this cleft and lake opened through the heart of the preserve. Probably the river once ran far up there where the starlight was crowning the blue cliffs with a silver diadem of light, only when this hollow opened did it slowly deepen a lower course, spreading out in a lake, and eventually tumbling down those icy steps lose itself in the dark roots of the hills. It was very simple, no doubt, but incredibly weird and wonderful to me who stood, the sole living thing in that immense concourse of dead humanity.

Look where I would it was the same everywhere. Those endless rows of frozen bodies lying, sitting, or standing stared at me from every niche and cornice. It almost seemed, as the light veered slowly round, as though they smiled and frowned at times, but never a word was there amongst those millions; the silence itself was audible, and save the dull low thunder of the fall, so monotonous the ear became accustomed to and soon disregarded it, there was not a sound anywhere, not a rustle, not a whisper broke the eternal calm of that great caravansary of the dead.

The very rattle of the shingle under my feet and the jingle of my navy scabbard seemed offensive in the perfect hush, and, too awed to be frightened, I presently turned away from the dreadful shine of those cliffs and felt my way along the base of the wall on my own side. There was no means of escape that way, and presently the shingle beach itself gave out as stated, where the cliff wall rose straight from the surface of the lake, so I turned back, and finding a grotto in the ice determined to make myself as comfortable as might be until daylight came.

Fortunately there was a good deal of broken timber thrown up at “high-water” mark, and with a stack of this at the mouth of the little cave a pleasant fire was soon made by help of a flint pebble and the steel back of my sword. It was a hearty blaze and lit up all the near cliffs with a ruddy jumping glow which gave their occupants a marvellous appearance of life. The heat also brought off the dull rime upon the side of my recess, leaving it clear as polished glass, and I was a little startled to see, only an inch or so back in the ice and standing as erect as ever he had been in life, the figure of an imposing grey clad man. His arms were folded, his chin dropped upon his chest, his robes of the finest stuff, the very flowers they had decked his head with frozen with immortality, and under them, round his crisp and iron-grey hair, a simple band of gold with strange runes and figures engraved upon it.

There was something very simple yet stately about him, though his face was hidden and as I gazed long and intently the idea got hold of me that he had been a king over an undegenerate Martian race, and had stood waiting for the Dawn a very, very long time.

I wished a little that he had not been quite so near the glassy surface of the ice down which the warmth was bringing quick moisture drops. Had he been back there in the blue depths where others were sitting and crouching it would have been much more comfortable. But I was a sailor, and misfortune makes strange companions, so I piled up the fire again, and lying down presently on the dry shingle with my back to him stared moodily at the blaze till slowly the fatigues of the day told, my eyelids dropped and, with many a fitful start and turn, at length I slept.

It was an hour before dawn, the fire had burnt low and I was dreaming of an angry discussion with my tailor in New York as to the sit of my last new trousers when a faint sound of moving shingle caught my quick seaman ear, and before I could raise my head or lift a hand, a man’s weight was on me—a heavy, strong man who bore me down with irresistible force. I felt the slap of his ice-cold hand upon my throat and his teeth in the back of my neck! In an instant, though but half awake, with a yell of surprise and anger I grappled with the enemy, and exerting all my strength rolled him over. Over and over we went struggling towards the fire, and when I got him within a foot or so of it I came out on top, and, digging my knuckles into his throttle, banged his head upon the stony floor in reckless rage, until all of a sudden it seemed to me he was done for. I relaxed my grip, but the other man never moved. I shook him again, like a

Comments (0)