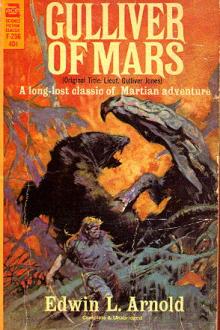

Gulliver of Mars - Edwin Lester Linden Arnold (great novels of all time txt) 📗

- Author: Edwin Lester Linden Arnold

- Performer: -

Book online «Gulliver of Mars - Edwin Lester Linden Arnold (great novels of all time txt) 📗». Author Edwin Lester Linden Arnold

“Hath!” I cried, rushing over to him, “wake up, your majesty. The Thither men are outside, killing and burning!”

“I know it.”

“And the palace is on fire. You can smell the reek even here.”

“Yes.”

“Then what are you going to do?”

“Nothing.”

“My word, that is a fine proposition for a prince! If you care nothing for town or palace perhaps you will bestir yourself for Princess Heru.”

A faint glimmer of interest rose upon the alabaster calm of his face at that name, but it faded instantly, and he said quietly,

“The slaves will save her. She will live. I looked into the book of her fate yesterday. She will escape, and forget, and sit at another marriage feast, and be a mother, and give the people yet one more prince to keep the faint glimmer of our ancestry alive. I am content.”

“But, d– it, man, I am not! I take a deal more interest in the young lady than you seem to, and have scoured half this precious planet of yours on her account, and will be hanged if I sit idly twiddling my thumbs while her pretty skin is in danger.” But Hath was lost in contemplation of his shoe-strings.

“Come, sir,” I said, shaking his majesty by the shoulder, “don’t be down on your luck. There has been some rivalry between us, but never mind about that just now. The princess wants you. I am going to save both her and you, you must come with her.”

“No.”

“But you SHALL come.”

“No!”

By this time the palace was blazing like a bonfire and the uproar outside was terrible. What was I to do? As I hesitated the arras at the further end of the hall was swept aside, a disordered mob of slaves bearing bundles and dragging Heru with them rushing down to the door near us. As Heru was carried swiftly by she stretched her milk-white arms towards the prince and turned her face, lovely as a convolvulus flower even in its pallor, upon him.

It was a heart-moving appeal from a woman with the heart of a child, and Hath rose to his feet while for a moment there shone a look of responsible manhood in his eyes. But it faded quickly; he bowed slowly as though he had received an address of condolence on the condition of his empire, and the next moment the frightened slaves, stumbling under their burdens, had swept poor Heru through the doorway.

I glanced savagely round at the curling smoke overhead, the red tendrils of fire climbing up a distant wall, and there on a table by us was a half-finished flask of the lovely tinted wine of forgetfulness. If Hath would not come sober perhaps he might come drunk.

“Here,” I cried, “drink to tomorrow, your majesty, a sovereign toast in all ages, and better luck next time with these hairy gentlemen battering at your majesty’s doors,” and splashing out a goblet full of the stuff I handed it to him.

He took it and looked rather lovingly into the limpid pool, then deliberately poured it on the step in front of him, and throwing the cup away said pleasantly,

“Not tonight, good comrade; tonight I drink a deeper draught of oblivion than that,—and here come my cup-bearers.”

Even while he spoke the palace gates had given way; there was a horrible medley of shrieks and cries, a quick sound of running feet; then again the arras lifted and in poured a horde of Ar-hap’s men-at-arms. The moment they caught sight of us about a dozen of them, armed with bows, drew the thick hide strings to their ears and down the hall came a ravening flight of shafts. One went through my cap, two stuck quivering in the throne, and one, winged with owl feather, caught black Hath full in the bosom.

He had stood out boldly at the first coming of that onset, arms crossed on breast, chin up, and looking more of a gentleman than I had ever seen him look before; and now, stricken, he smiled gravely, then without flinching, and still eyeing his enemies with gentle calm, his knees unlocked, his frame trembled, then down he went headlong, his red blood running forth in rivulets amongst the wine of oblivion he had just poured out.

There was no time for sentiment. I shrugged my shoulders, and turning on my heels, with the woodmen close after me, sprang through the near doorway. Where was Heru? I flew down the corridor by which it seemed she had retreated, and then, hesitating a moment where it divided in two, took the left one. This to my chagrin presently began to trend upwards, whereas I knew Heru was making for the river down below.

But it was impossible to go back, and whenever I stopped in those deserted passages I could hear the wolflike patter of men’s feet upon my trail. On again into the stony labyrinths of the old palace, ever upwards, in spite of my desire to go down, until at last, the pursuers off the track for a moment, I came to a north window in the palace wall, and, hot and breathless, stayed to look out.

All was peace here; the sky a lovely lavender, a promise of coming morning in it, and a gold-spangled curtain of stars out yonder on the horizon. Not a soul moved. Below appeared a sheer drop of a hundred feet into a moat winding through thickets of heavy-scented convolvulus flowers to the waterways beyond. And as I looked a skiff with half a dozen rowers came swiftly out of the darkness of the wall and passed like a shadow amongst the thickets. In the prow was all Hath’s wedding plate, and in the stern, a faint vision of unconscious loveliness, lay Heru!

Before I could lift a finger or call out, even if I had had a mind to do so, the shadow had gone round a bend, and a shout within the palace told me I was sighted again.

On once more, hotly pursued, until the last corridor ended in two doors leading into a half-lit gallery with open windows at the further end. There was a wilderness of lumber down the sides of the great garret, and now I come to think of it more calmly I imagine it was Hath’s Lost Property Office, the vast receptacle where his slaves deposited everything lazy Martians forgot or left about in their daily life. At that moment it only represented a last refuge, and into it I dashed, swung the doors to and fastened them just as the foremost of Ar-hap’s men hurled themselves upon the barrier from outside.

There I was like a rat in a trap, and like a rat I made up my mind to fight savagely to the end, without for a moment deceiving myself as to what that end must be. Even up there the horrible roar of destruction was plainly audible as the barbarians sacked and burned the ancient town, and I was glad from the bottom of my heart my poor little princess was safely out of it. Nor did I bear her or hers the least resentment for making off while there was yet time and leaving me to my fate—anything else would have been contrary to Martian nature. Doubtless she would get away, as Hath had said, and elsewhere drop a few pearly tears and then over her sugar-candy and lotus-eating forget with happy completeness—most blessed gift! And meanwhile the foresaid barbarians were battering on my doors, while over their heads choking smoke was pouring in in ever-increas-ing volumes.

In burst the first panel, then another, and I could see through the gaps a medley of tossing weapons and wild faces without. Short shrift for me if they came through, so in the obstinacy of desperation I set to work to pile old furniture and dry goods against the barricade. And as they yelled and hammered outside I screamed back defiance from within, sweating, tugging, and hauling with the strength of ten men, piling up the old Martian lumber against the opening till, so fierce was the attack outside, little was left of the original doorway and nothing between me and the beseigers but a rampart of broken woodwork half seen in a smother of smoke and flames.

Still they came on, thrusting spears and javelins through every crevice and my strength began to go. I threw two tables into a gap, and brained a besieger with a sweetmeat-seller’s block and smothered another, and overturned a great chest against my barricade; but what was the purpose of it all? They were fifty to one and my rampart quaked before them. The smoke was stifling, and the pains of dissolution in my heart. They burst in and clambered up the rampart like black ants. I looked round for still one more thing to hurl into the breach. My eyes lit on a roll of carpet: I seized it by one corner meaning to drag it to the doorway, and it came undone at a touch.

That strange, that incredible pattern! Where in all the vicissitudes of a chequered career had I seen such a one before? I stared at it in amazement under the very spears of the woodmen in the red glare of Hath’s burning palace. Then all on a sudden it burst upon me that IT WAS THE ACCURSED RUG, the very one which in response to a careless wish had swept me out of my own dear world, and forced me to take as wild a journey into space as ever fell to a man’s lot since the universe was made!

And in another second it occurred to me that if it had brought me hither it might take me hence. It was but a chance, yet worth trying when all other chances were against me. As Ar-hap’s men came shouting over the barricade I threw myself down upon that incredible carpet and cried from the bottom of my heart,

“I wish—I wish I were in New York!”

Yes!

A moment of thrilling suspense and then the corners lifted as though a strong breeze were playing upon them. Another moment and they had curled over like an incoming surge. One swift glance I got at the smoke and flames, the glittering spears and angry faces, and then fold upon fold, a stifling, all-enveloping embrace, a lift, a sense of super-human speed—and then forgetfulness.

When I came to, as reporters say, I was aware the rug had ejected me on solid ground and disappeared, forever. Where was I! It was cool, damp, and muddy. There were some iron railings close at hand and a street lamp overhead. These things showed clearly to me, sitting on a doorstep under that light, head in hand, amazed and giddy—so amazed that when slowly the recognition came of the incredible fact my wish was gratified and I was home again, the stupendous incident scarcely appealed to my tingling senses more than one of the many others I had lately undergone.

Very slowly I rose to my feet, and as like a discreditable reveller as could be, climbed the steps. The front door was open, and entering the oh, so familiar hall a sound of voices in my sitting-room on the right caught

Comments (0)