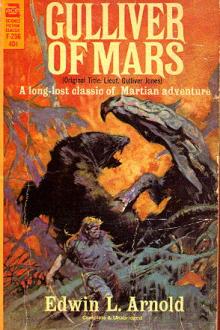

Gulliver of Mars - Edwin Lester Linden Arnold (great novels of all time txt) 📗

- Author: Edwin Lester Linden Arnold

- Performer: -

Book online «Gulliver of Mars - Edwin Lester Linden Arnold (great novels of all time txt) 📗». Author Edwin Lester Linden Arnold

When my friendly companion found I could not understand him, he looked serious for a minute or two, then shortened his brilliant yellow toga, as though he had arrived at some resolve, and knelt down directly in front of me. He next took my face between his hands, and putting his nose within an inch of mine, stared into my eyes with all his might. At first I was inclined to laugh, but before long the most curious sensations took hold of me. They commenced with a thrill which passed all up my body, and next all feeling save the consciousness of the loud beating of my heart ceased. Then it seemed that boy’s eyes were inside my head and not outside, while along with them an intangible something pervaded my brain. The sensation at first was like the application of ether to the skin—a cool, numbing emotion. It was followed by a curious tingling feeling, as some dormant cells in my mind answered to the thought-transfer, and were filled and fertilised! My other brain-cells most distinctly felt the vitalising of their companions, and for about a minute I experienced extreme nausea and a headache such as comes from over-study, though both passed swiftly off. I presume that in the future we shall all obtain knowledge in this way. The Professors of a later day will perhaps keep shops for the sale of miscellaneous information, and we shall drop in and be inflated with learning just as the bicyclist gets his tire pumped up, or the motorist is recharged with electricity at so much per unit. Examinations will then become matters of capacity in the real meaning of that word, and we shall be tempted to invest our pocket-money by advertisements of “A cheap line in Astrology,” “Try our double-strength, two-minute course of Classics,” “This is remnant day for Trigonometry and Metaphysics,” and so on.

My friend did not get as far as that. With him the process did not take more than a minute, but it was startling in its results, and reduced me to an extraordinary state of hypnotic receptibility. When it was over my instructor tapped with a finger on my lips, uttering aloud as he did so the words—

“Know none; know some; know little; know morel” again and again; and the strangest part of it is that as he spoke I did know at first a little, then more, and still more, by swift accumulation, of his speech and meaning. In fact, when presently he suddenly laid a hand over my eyes and then let go of my head with a pleasantly put question as to how I felt, I had no difficulty whatever in answering him in his own tongue, and rose from the ground as one gets from a hair-dresser’s chair, with a vague idea of looking round for my hat and offering him his fee.

“My word, sir!” I said, in lisping Martian, as I pulled down my cuffs and put my cravat straight, “that was a quick process. I once heard of a man who learnt a language in the moments he gave each day to having his boots blacked; but this beats all. I trust I was a docile pupil?”

“Oh, fairly, sir,” answered the soft, musical voice of the strange being by me; “but your head is thick and your brain tough. I could have taught another in half the time.”

“Curiously enough,” was my response, “those are almost the very words with which my dear old tutor dismissed me the morning I left college. Never mind, the thing is done. Shall I pay you anything?”

“I do not understand.”

“Any honorarium, then? Some people understand one word and not the other.” But the boy only shook his head in answer.

Strangely enough, I was not greatly surprised all this time either at the novelty of my whereabouts or at the hypnotic instruction in a new language just received. Perhaps it was because my head still spun too giddily with that flight in the old rug for much thought; perhaps because I did not yet fully realise the thing that had happened. But, anyhow, there is the fact, which, like so many others in my narrative, must, alas! remain unexplained for the moment. The rug, by the way, had completely disappeared, my friend comforting me on this score, however, by saying he had seen it rolled up and taken away by one whom he knew.

“We are very tidy people here, stranger,” he said, “and everything found Lying about goes back to the Palace store-rooms. You will laugh to see the lumber there, for few of us ever take the trouble to reclaim our property.”

Heaven knows I was in no laughing mood when I saw that enchanted web again!

When I had lain and watched the brightening scene for a time, I got up, and having stretched and shaken my clothes into some sort of order, we strolled down the hill and joined the lighthearted crowds that twined across the plain and through the streets of their city of booths. They were the prettiest, daintiest folk ever eyes looked upon, well-formed and like to us as could be in the main, but slender and willowy, so dainty and light, both the men and the women, so pretty of cheek and hair, so mild of aspect, I felt, as I strode amongst them, I could have plucked them like flowers and bound them up in bunches with my belt. And yet somehow I liked them from the first minute; such a happy, careless, lighthearted race, again I say, never was seen before. There was not a stain of thought or care on a single one of those white foreheads that eddied round me under their peaked, blossom-like caps, the perpetual smile their faces wore never suffered rebuke anywhere; their very movements were graceful and slow, their laughter was low and musical, there was an odour of friendly, slothful happiness about them that made me admire whether I would or no.

Unfortunately I was not able to live on laughter, as they appeared to be, so presently turning to my acquaintance, who had told me his name was the plain monosyllabic An, and clapping my hand on his shoulder as he stood lost in sleepy reflection, said, in a good, hearty way, “Hullo, friend Yellow-jerkin! If a stranger might set himself athwart the cheerful current of your meditations, may such a one ask how far ‘tis to the nearest wine-shop or a booth where a thirsty man may get a mug of ale at a moderate reckoning?”

That gilded youth staggered under my friendly blow as though the hammer of Thor himself had suddenly lit upon his shoulder, and ruefully rubbing his tender skin, he turned on me mild, handsome eyes, answering after a moment, during which his native mildness struggled with the pain I had unwittingly given him—

“If your thirst be as emphatic as your greeting, friend Heavy-fist, it will certainly be a kindly deed to lead you to the drinking-place. My shoulder tingles with your good-fellowship,” he added, keeping two arms’-lengths clear of me. “Do you wish,” he said, “merely to cleanse a dusty throat, or for blue or pink oblivion?”

“Why,” I answered laughingly, “I have come a longish journey since yesterday night—a journey out of count of all reasonable mileage—and I might fairly plead a dusty throat as excuse for a beginning; but as to the other things mentioned, those tinted forgetfulnesses, I do not even know what you mean.”

“Undoubtedly you are a stranger,” said the friendly youth, eyeing me from top to toe with renewed wonder, “and by your unknown garb one from afar.”

“From how far no man can say—not even I—but from very far, in truth. Let that stay your curiosity for the time. And now to bench and ale-mug, on good fellow!—the shortest way. I was never so thirsty as this since our water-butts went overboard when I sailed the southern seas as a tramp apprentice, and for three days we had to damp our black tongues with the puddles the night-dews left in the lift of our mainsail.”

Without more words, being a little awed of me, I thought, the boy led me through the good-humoured crowd to where, facing the main road to the town, but a little sheltered by a thicket of trees covered with gigantic pink blossoms, stood a drinking-place—a cluster of tables set round an open grass-plot. Here he brought me a platter of some light inefficient cakes which merely served to make hunger more self-conscious, and some fine aromatic wine contained in a triple-bodied flask, each division containing vintage of a separate hue. We broke our biscuits, sipped that mysterious wine, and talked of many things until at last something set us on the subject of astronomy, a study I found my dapper gallant had some knowledge of—which was not to be wondered at seeing he dwelt under skies each night set thick above his curly head with tawny planets, and glittering constellations sprinkled through space like flowers in May meadows. He knew what worlds went round the sun, larger or lesser, and seeing this I began to question him, for I was uneasy in my innermost mind and, you will remember, so far had no certain knowledge of where I was, only a dim, restless suspicion that I had come beyond the ken of all men’s knowledge.

Therefore, sweeping clear the board with my sleeve, and breaking the wafer cake I was eating, I set down one central piece for the sun, and, “See here!” I said, “good fellow! This morsel shall stand for that sun you have just been welcoming back with quaint ritual. Now stretch your starry knowledge to the utmost, and put down that tankard for a moment. If this be yonder sun and this lesser crumb be the outermost one of our revolving system, and this the next within, and this the next, and so on; now if this be so tell me which of these fragmentary orbs is ours—which of all these crumbs from the hand of the primordial would be that we stand upon?” And I waited with an anxiety a light manner thinly hid, to hear his answer.

It came at once. Laughing as though the question were too trivial, and more to humour my wayward fancy than aught else, that boy circled his rosy thumb about a minute and brought it down on the planet Mars!

I started and stared at him; then all of a tremble cried, “You trifle with me! Choose again—there, see, I will set the symbols and name them to you anew. There now, on your soul tell me truly which this planet is, the one here at our feet?” And again the boy shook his head, wondering at my eagerness, and pointed to Mars, saying gently as he did so the fact was certain as the day above us, nothing was marvellous but my questioning.

Mars! oh, dreadful, tremendous, unexpected! With a cry of affright, and bringing my fist down on the table till all the cups upon it leapt, I told him he lied—lied like a simpleton whose astronomy was as rotten as his wit—smote

Comments (0)