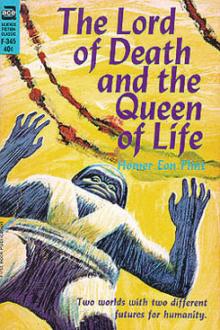

The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life - Homer Eon Flint (online e book reading txt) 📗

- Author: Homer Eon Flint

- Performer: -

Book online «The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life - Homer Eon Flint (online e book reading txt) 📗». Author Homer Eon Flint

My mind was more alive than it had ever been before. “Now, what caused that, Maka? The lightning, I mean; we have it nearly every day, yet I have never thought to question it before.”

“It is no mystery, my lad,” quoth Maka, dodging into his chariot, so that he was not wet. “I myself have watched the thing from the top of high mountains, where the air is so light that a man can scarce get enough to fill his lungs; and I say unto you that, were it not for what air we have, we should have naught save the lightning. The space about the air is full of it.”

He started his engine, then leaned out into the rain and said softly: “Hold fast to what thy father has taught thee, Strokor. Have nothing to do with the women. ‘Tis a man’s job ahead of thee, and the future of the empire is in thy hands.

“And,” as he clattered off, “fill not thy head with wonderings about the lightning.”

“Aye,” said I right earnestly, and immediately turned my thoughts to my new ambition. And yet the thing Maka had just told me kept coming back to my mind, and so it does to this very day. I know not why I should mention it at all save that each time I think upon Maka, I also think upon the lightning, whether I will or no.

I slept not at all that night, but sat [Footnote: It seems to have been the custom among the soldiers never to lie down, but to take their sleep sitting or standing; a habit not hard to form where the gravitation was so slight. No doubt this also explains their stunted legs.] till the dawn came, thinking out a plan of action. By that time I was fair convinced that there was naught to be gained by waiting; waiting makes me impatient as well. I determined to act at once; and since one day is quite as good as the next, I decided that this day was to see the thing begun.

I came before the emperor at noon and received my decorations. Within the hour I had made myself known to the four and ninety men who were to be my command; a picked company, all of a height and weight, with bodies that lacked little of my own perfection. Never was there a finer guard about the palace.

My first care was to pick a quarrel with the outgoing commander. Twere easy enough; he was green with envy, anyhow. And so it came about that we met about mid afternoon, with seconds, in a well-frequented field in the outskirts.

Before supper was eaten my entire troop knew that their new captain had tossed his ball-slinger away without using it, had taken twenty balls from their former commander’s weapon, and while thus wounded had charged the man and despatched him with bare hands! Needless to say, this exploit quite won their hearts; none but a blind man could have missed the respect they showed me when, all bandaged and sore, I lined them up next morning. Afterward I learned that they had all taken a pledge to “follow Strokor through the gates of Hofe itself!”

‘Twere but a week later that, fully recovered and in perfect fettle, I called my men together one morn as the sun rose. By that time I had given them a sample of my brains through ordering a rearrangement of their quarters such as made the same much more comfortable. Also, I had dealt with one slight infraction of the rules in such a drastic fashion that they knew I would brook no trifling. All told, ‘tis hard to say whether they thought the most of me or of Jon.

“Men,” said I, as bluntly as I knew, “the emperor is an old man. And, as ye know, he is disposed to be lenient toward the men of Klow; whereas, ye and I well know that the louts are blackguards.

“Now, I will tell ye more. It has come to me lately that Klow is plotting to attack us with strange weapons.” I thought best, considering their ignorance, not to give them my own reasons. “Of course I have told the emperor of it; yet he will not act. He says to wait till we are attacked.”

I stopped and watched their faces. Sure enough; the idea fair made them ache. Each and every one of these men was spoiling for a fight.

“Now, tell me; how would ye like to become the emperor’s body-guard?” I did not have to wait long; the light that flared in their faces told me plainly. “And—how would ye like to have me for your emperor?”

At that their tongues were loosed, and I hindered them not. They yelled for pure joy, and pressed about me like a pack of children. I saw that the time was ripe for action.

“Up, then!” I roared, and, of course, led the way. We met the emperor’s guard on the lower stairs; and from that point on we fair hacked our way through.

Well, no need to describe the fight. For a time I thought we were gone; the guards had a cunningly devised labyrinth on the second floor, and attacked us from holes in a false ceiling, so that we suffered heavily at first. But I saw what was amiss, and shouted to my men to clear away the timbers; and after that it was clear work. I lost forty men before the guard was disposed of. The emperor I finished myself; he dodged right spryly for a time, but at last I caught him and tossed him to the foot of the upper stairs. And there he still lies for none of my men would touch him, nor would I. We covered him with quicklime and some earth.

As soon as we had taken care of those who were not too far gone, I called the men together and caused a round of spirits to be served. Then we all feasted on the emperor’s store, and soon were feeling like ourselves.

“Men,” I said impressively, “I am proud of ye. Never did an emperor have such a dangerous gang of bullies!”

At that they all grinned happily, and I added: “And ‘tis a fine staff of generals that ye’ll make!”

Need I say more? Those men would have overturned the palace for me had I said the word. As it was, they obeyed my next orders in such a spirit that success was assured from the first.

First, using the dead emperor’s name, I caused the various chiefs to be brought together at once to the court chamber. At the same time I contrived, by means I need not go into here, to prevent any word of our action from getting abroad. So, when the former staff faced me the next morning, they learned that they were to be executed. I could trust not one; they were all friends of the old man.

With the chiefs out of the way, and my own men taking their commands, the whole army fell into my hands. True, there were some insurrections here and there; but my men handled them with such speed and harshness that any further stubbornness turned to admiration. By this time the fame of Strokor was spread throughout the empire.

And thus it came about that, within a week of the night that old Maka first put the idea into my head, Strokor, son of Strok, reigned throughout Vlamaland. And, to make it complete, the army celebrated my accession by taking a pledge before Jon:

“To Strokor, the fittest of the fit!”

IV THE ASSAULTNow, out of a total population of perhaps three million, I had about a quarter-million first-class fighters in my half of the world. Klow, by comparison, had but two-thirds the number; his land was not a rich one.

But he had the advantage of knowing, some while in advance, of the new ruler in Vlama; and shortly my spies reported that his armories were devising a new type of weapon. ‘Twas a strange verification of my own fiction to my men. I could learn nothing, however, about it.

Meanwhile I caused a vast number of flat-boats to be built, all in secret. Each of them was intended for a single fighter and his supplies; and each was so arranged, with side paddle wheels, that it would be driven by the motor in the soldier’s chariot, and thus give each his own boat.

Again discarding all precedent, I packed not all my forces together, as had been done in the past, but scattered them up and adown the coast fronting the land of Klow; and at a prearranged time my quarter-million men set out, a company in each tiny fleet. Some were slightly in advance of the rest, who had the shorter distance to travel. And, just as I had planned, we all arrived at a certain spot on Klow’s coast at practically the same hour, although two nights later.

‘Twas a brilliant stroke. The enemy looked not for a fleet of water-ants, ready to step right out of the sea into battle. Their fleet was looking for us, true, but not in that shape. And we were all safely ashore before they had ceased to scour the seas for us.

I immediately placed my heavy machines, and just as all former expeditions had done, opened the assault at once with a shower of the poison shells. I relied, it will be seen, upon the surprise of my attack to strike terror into the hearts of the louts.

But apparently they were prepared for anything, no matter how rapid the attack. My bombardment had not proceeded many moments before, to my dismay, some of their own shells began to fall among us. Soon they were giving as good as we.

“Now, how knew they that we should come to this spot?” I demanded of Maka. I had placed him in my cabinet as soon as I had reached the throne.

The old man stroked his beard gravely. “Perchance it had been wrong to come to the old landing. They simply began shelling it as a matter of course.”

“Ye are right again,” I told him; and forthwith moved my pieces over into another triangle. (Previously, of course, all my charioteers had gone on toward the capital). However, I took care to move my machines, one at a time, so that there was no let-up in my bombardment.

But scarce had we taken up the new position before the enemy’s shells likewise shifted, and began to strike once more in our midst. I swore a great oath and whirled upon Maka in wrath.

“Think ye that there be a spy among us?” I demanded. “How else can ye explain this thing? My men have combed the land about us; there are none of the louts secreted here; and, even so, they could not have notified Klow so soon. Besides, ‘tis pitch dark.” I were sorely mystified.

All we could do was to fling our shells as fast as our machines would work and dodge the enemy’s hail as best we could. Thus the time passed, and it were near dawn when the first messengers [Footnote: Messengers; no telegraph or telephone, much less wireless. In a civilization as strenuous as that of Mercury, there was never enough consideration for others to lead to such socially beneficial things as these, no more than railroads or printing presses. Civilization appears to be in exact proportion to the ease of

Comments (0)